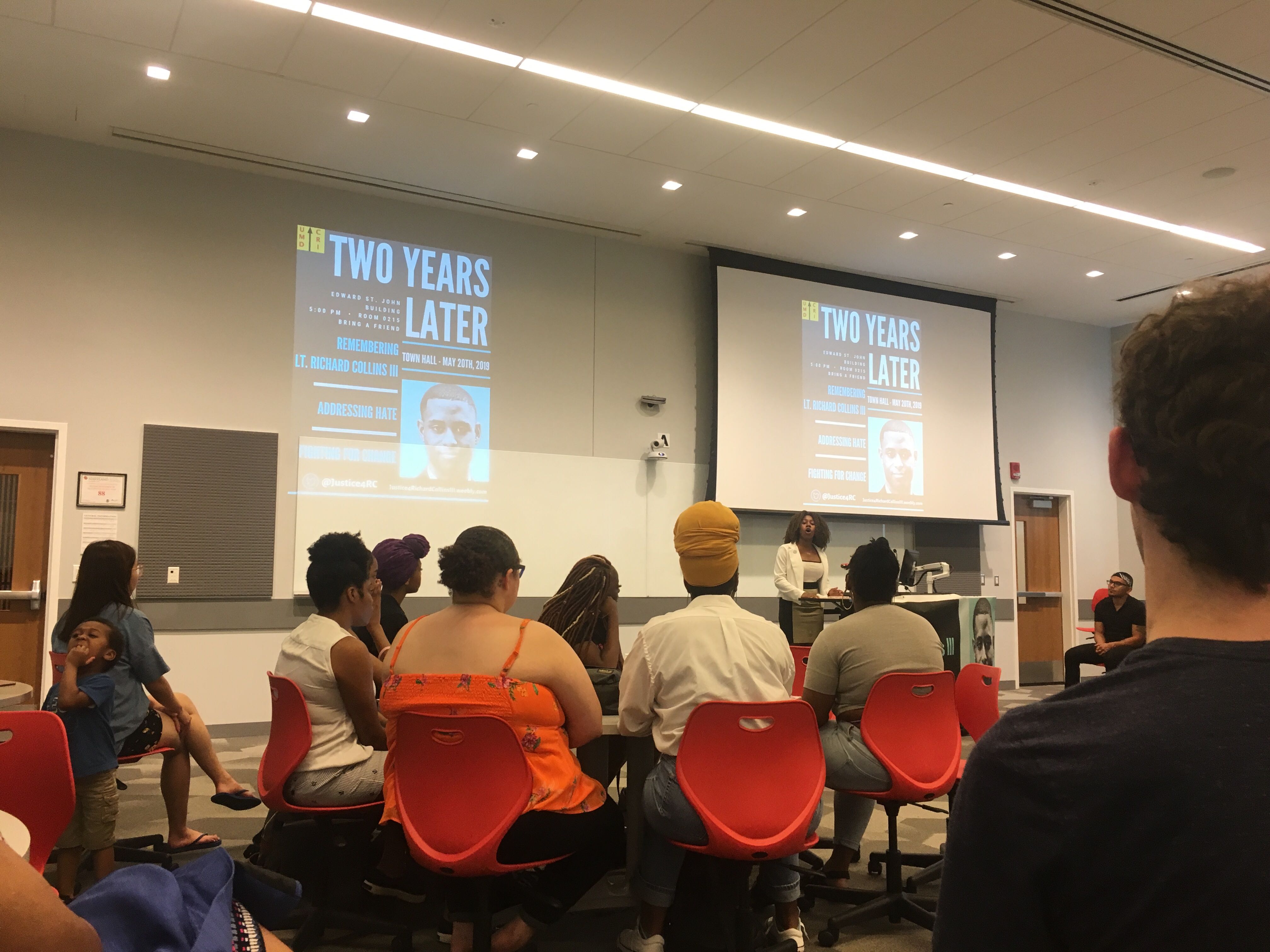

Exactly two years after 2nd Lt. Richard Collins was killed on the University of Maryland’s campus, university President Wallace Loh implored a room of students, faculty and Collins’ family to trust that steps would be taken to memorialize the young man’s life.

“He will be remembered on this campus in a very, very significant way,” Loh told the crowd of about 40 people who had gathered for a town hall Monday to honor Collins and discuss hate on the campus. “He gave his life.”

Collins, a black Bowie State University student, was fatally stabbed on May 20, 2017, while waiting for an Uber near Montgomery Hall. Sean Urbanski, a white former student of this university who was a member of a now-deactivated white supremacist Facebook group, is set to stand trial in July for charges of murder and a hate crime in the killing.

Though Loh emphasized the steps his administration has taken to address issues facing students of color — and that the campus community would learn about plans to construct a permanent memorial to Collins “when the appropriate time comes” — many in the audience weren’t impressed by his remarks.

Soon after the president retook his seat, sociology doctoral student Asiah Gayfield addressed the crowd, saying that Loh’s words embodied exactly what bothered her about the university’s response to Collins’ death — for starters, she said, the Bowie State University student didn’t “give his life.”

“His life was taken,” she said. “And it was taken on this campus.”

Gayfield also took issue with the way Loh spoke about the university’s sharp decline in African American freshman enrollment. Just 7.3 percent of this year’s freshman class was African American — an over 30 percent decrease from last academic year, and the lowest enrollment since the Institutional Research, Planning and Assessment office started keeping track in 1992.

[Read more: “We are Lt. Collins”: UMD and Bowie State students gather for panel on racism]

Loh defended the admissions office, saying they placed about 1,700 calls to African American prospective students who had applied to the university but hadn’t included required documents — such as recommendation letters or transcripts — to give them a chance to send these materials rather than discarding their applications without any notice.

But Gayfield said Loh was “missing the point” when he talked about these numbers and the math behind the drop. Instead, she said, Loh should focus on whether marginalized students would be protected after they enroll.

“I have not seen anything that tells me that I can feel safe recruiting students to this university,” she said. “And I don’t do it. I do not tell students who look like me to come to this university.”

Throughout the town hall, which this campus’ chapter of the NAACP, the Political Latinxs United for Movement and Action in Society and the Critical Race Initiative hosted, a number of students raised ideas for how the school could combat hate and honor Collins’ memory.

Bria Goode, a senior public health science major and an Alpha Kappa Alpha member, suggested the university require students to take cultural competency training — similar to AlcoholEdu — before arriving on the campus, or in UNIV100 courses, which are required for many freshmen.

Loh said new training for the fall semester is in development — a fact that isn’t widely known because his administration simply “[does] the work” and doesn’t “go around talking about it.”

“The question is, ‘Why don’t I share more?’” he said. “Because there’s such a thing of doing your job, as opposed to just going out and doing PR.”

In the wake of Collins’ death, the university established a diversity task force to review campus policies, commissioned an external review of diversity and inclusion on the campus and announced the creation of a diversity and inclusion vice president role, which Georgina Dodge, Bucknell University’s chief diversity officer, will assume in June.

It also launched a campus climate survey, the full results of which became public earlier this month and showed that safety concerns and detachment were higher among minority students than white students.

Sociology doctoral student Jessica Shotwell said the university should create a scholarship for student activists in Collins’ memory.

[Read more: Sean Urbanski’s trial has been postponed for a third time]

Shotwell, one of the town hall’s organizers, also joined many of those in attendance who called for the demolition of the bus stop where Collins was killed and the construction of a permanent memorial in its place.

Since September 2017, the bus stop near Montgomery Hall has been blocked. But freshman Sabrina Pierre said she still sees students — particularly drunk ones — sitting on the bench. She’s bewildered and outraged that the bus stop is still standing and that more hasn’t been done to honor Collins’ memory.

“You guys could at least put up a nice sign, better barriers,” Pierre, a government and politics and sociology major, said. “You could put up a nice painting of him. It’s ridiculous … They haven’t even done the bare minimum.”

Loh has said that he’s waiting for Collins’ family’s input before moving forward with a permanent memorial. He first announced the university would build one in April 2018.

But Goode said she was still heartbroken that Collins’ life is marked only by a single sheet of paper hanging on the wall of the bus stop where he was killed.

“He was meant to do a lot of great things,” she said. “I know that at the end of the day nothing can make up for it — but something must be done.”

In the meantime, Collins’ mother told the audience it could help memorialize her son by emulating his values and spreading his story.

“Am I sad today? Absolutely. But I’m also proud of the man that he would [have] become. Because he did say to me, ‘Mom, the world is going to know my name,’” she said. “Each and every one of you in this room can make that legacy happen.”

CORRECTION: Due to a reporting error, a previous version of this story stated Bria Goode is a NAACP member. She is not. This story has been updated.