University of Maryland workers gathered at a forum Friday to demand a campuswide salary increase.

At the event, organized by this university’s chapter of United Students Against Sweatshops, workers at the university spoke out for higher wages.

“They need to do a salary increase,” Rhonda Leneski, a Residential Facilities housekeeper, said at the forum. “Everybody. The whole campus.”

The desire for a pay increase among non-exempt workers — employees who are paid hourly and must be given overtime if they work more than 40 hours in a week— has been reignited with the recent release of a financial analysis commissioned by this university’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors.

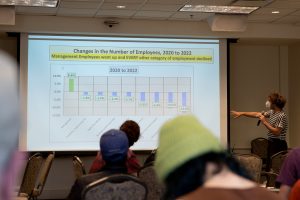

The AAUP analysis showed that management employees — who have an exempt status— have been paid far more than every other employment category on campus. According to the analysis, the average salary of service workers is more than five times lower than the average salary of a manager.

In small discussion groups at the forum, union leaders, housekeepers, an IT coordinator and student workers made lists of concrete labor demands and goals to submit to the university for next semester.

Workers criticized the university’s reliance on contractual employees. C-1 contractual employees are considered seasonal or intermittent workers and repeatedly sign temporary employment contracts to continue working at this university.

C-2 contractual employees get more benefits than C-1 employees. In the university’s dining halls, C-2 employees have to work for three years before they’re considered for a full-time position, according to Ulric Bethel, a Dining Services cook and food manager.

[UMD students, faculty discuss importance of student debt cancellation]

Bethel works with many C-1 employees, whom he says are the majority at dining halls. Bethel said C-1 employees do not have benefits.

“You can be working 10, 12, 15, 20 years as a C-1,” Bethel said.

Saul Walker, the multi-trade chief at the University of Maryland’s Residential Facilities department, added that contractual workers are at-will employees, meaning they can be terminated at any time for almost any reason.

Walker said at the forum this university should no longer use contractual workers and should follow the model of Morgan State University, which stopped hiring contractual staff in August 2021. The historically Black university did this to “address employee inequity in a profound and meaningful way,” according to a news release.

Multiple workers, including Leneski and a graduate research assistant, also spoke at the forum about feeling overworked.

“It’s all about the money,” Leneski said. “The money is a little bit, but the workload is so big, it’s got people running from the job.”

Leneski said in her experience, some potential new hires decide not to work as housekeepers at this university because of the low pay and the hard work. She also said she feels like managers do not give new housekeepers “room to breathe.”

“They are going to be pushing the maid, ‘This has to [get] done, that has to [get] done, that has to [get] done,’” Leneski said.

Andrew Goffin, a graduate research assistant at the Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics, said he is “fairly lucky” with his workload because of his advisor. Other graduate student workers may have a different experience, Goffin said.

“There is sort of an expectation from a lot of advisors that you’re working — especially in the STEM fields — that means, ‘Oh, you’re supposed to be passionate about science.’ What does that passion mean? That means you work basically every day. You work 12 hours a day. You publish, publish, publish, work nonstop,” Goffin said.

[New UMD AAUP financial analysis finds student fees keep athletics profitable]

Goffin added there is supposed to be a limit on how much graduate students work, but the language of their contracts can cause them to work much more than the limit, Goffin said.

“You’re supposed to average 20 hours a week over the course of the semester,” Goffin said. “If you work 30 hours one week, the grad school looks at that and they say, ‘Well, that’s fine.’”

Undergraduate student workers also voiced their concerns at the forum regarding sexual misconduct.

Harrison Wu, a senior kinesiology major, has worked at RecWell for all four years he has attended this university. He said the process for sexual misconduct reporting in the workplace is not adequate.

“In terms of sexual harassment, there’s no orientations. We’re never taught what the process is for filing that complaint. It generally just comes down to, ‘Talk to your student supervisor,’ and the student supervisor will talk to the actual boss,” Wu said. “Then, we don’t hear anything about it.”

According to a statement from RecWell, students receive training about reporting sexual misconduct to professional staff. The statement said all RecWell professional staff are required to complete training from the Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct on how to report incidents of sexual misconduct.

Additionally, the RecWell statement said if students make a claim of sexual misconduct, they are counseled to report it to the Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct.

In a closing speech at the forum, Alena Sergueev, a junior government and politics major, expressed the importance of banding together for workers’ rights.

Sergueev, a member of this university’s USAS chapter, worked at South Campus Dining Hall last semester and quit because she said the job was “exhausting.” She expressed concern for her former coworkers who rely on having a campus job.

“This isn’t about me though, necessarily. This is about all of us,” Sergueev said. “As workers, we have to demand our rights.”