Para leer este artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

As exit polls from the presidential election are analyzed, President-elect Joe Biden can say he secured about two-thirds of what has been dubbed the “Latino vote” — but that wouldn’t tell the whole story.

Much of the remaining Latino vote was cast for President Donald Trump, who has a history of strong anti-immigration rhetoric.

Immigration control was a huge part of his successful 2016 campaign, with thousands at his rallies chanting “build the wall” in support of preventing immigrants from crossing the U.S.-Mexico border — immigrants he described as “criminals,” “rapists” and “killers.”

This has led some to wonder: Why would any Latinos vote for Trump?

The Diamondback talked to three University of Maryland professors — two from this university’s U.S. Latina/o studies program and one who studies Latino politics — to figure out why.

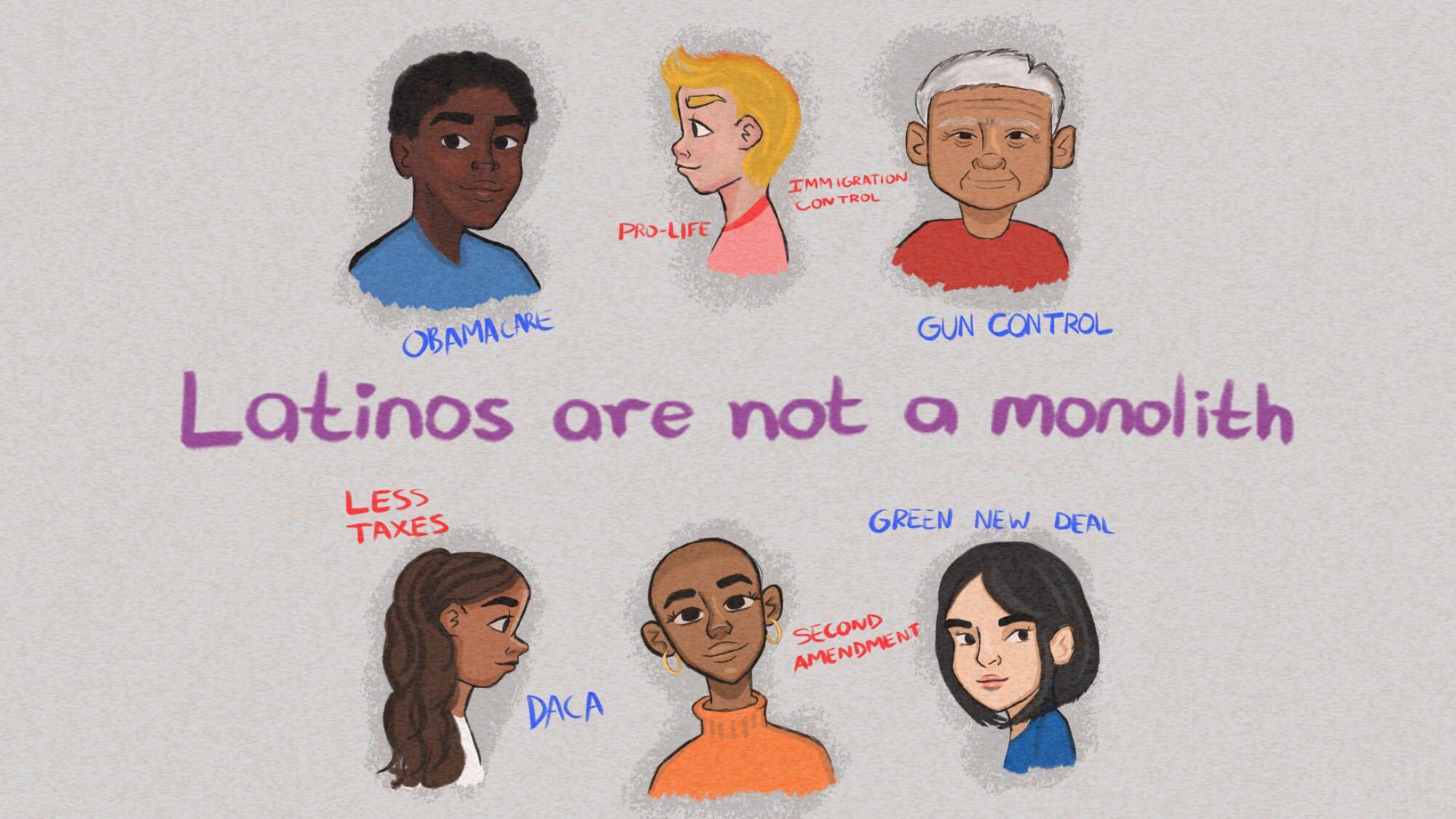

Their conclusion? Latinos are not a monolith.

The term “Latino” became popular in the 1990s, as an umbrella term to group together those with cultural ties to Latin America. It emerged as a more inclusive alternative to “Hispanic,” which excluded non-Spanish speaking countries such as Brazil and Haiti.

But while the term does a good job of grouping countries with a shared history of colonization, the Latino community is still very diverse — which is why some argue the Latino vote is a myth.

“There’s no such thing as the Latinx vote, it does not exist,” said Nancy Raquel Mirabal, director of the U.S. Latina/o studies program in this university’s American studies department. “There is no constituency that you can just get out to vote and assume that it’ll go a certain way. And the reason for that is because all of our histories are very different.”

That is, in the same way all white Americans don’t vote the same way, neither do all Latinos.

For starters, politicians must take into account the communities’ national origins, said Stella Rouse, a professor in the department of government and politics. Most Latinos first and foremost identify themselves by their family’s country or place of origin, Rouse said, using terms such as Cuban American or Mexican American. That should be more formative to pundits and politicians in how they reach out to these groups, she said.

[Afro-Latino students at UMD take pride in identities despite years of prejudices]

For example, Cuban Americans have routinely voted Republican since the Ronald Reagan era, Mirabal said. The Republican Party is good at targeting the fierce anti-communist sentiments of those voters, she said, many of whom lived under Fidel Castro’s socialist regime. It also makes sense that some Venezuelan Americans who come from a Venezuela led by Hugo Chávez or Nicolás Maduro would vote for Trump, Rouse said, especially given his campaign strategy.

The Trump campaign made deliberate efforts to portray Biden as a socialist, saying the United States would become a socialist country if he got elected, Rouse said. That played to the fears of Cuban and Venezuelan communities.

“It’s not right, all the misinformation that was given,” Rouse said. “But they just did a better job of trying to motivate Cubans, Venezuelans and other Latinos in that community to come out. And he overperformed with them.”

In contrast, the Biden campaign approached Latinos as a uniform electorate, not moving beyond his stance on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, Rouse said.

Mirabal said Biden’s support for DACA was the only time she felt Biden was talking directly to the Latino community.

“And I kept thinking, why didn’t Biden do more of that?” she said.

And while immigration is important for many Latinos, it does not resonate with all of them equally — that will depend on where they live and how long they have been in the United States, Rouse said.

For instance, Latino voters in the Southwestern states that share a border with Mexico will see immigration differently than Latinos in Florida, Mirabal said. Similarly, Latinos with undocumented families may be more pro-immigration than Latinos who have been in the country for generations. These third or fourth generation Latinos may even worry that an increased influx of immigrants could threaten their jobs, Rouse said.

In Maryland, where many Latinos have experience with temporary protected status, the community might be more interested in the path to citizenship than in other states said Perla Guerrero, a professor in the U.S. Latina/o studies program. In Georgia, where undocumented students cannot enroll in some public institutions, the focus may be on education, Guerrero said.

Their professions can also play a role in their political ideology. Business owners might think they would benefit more from deregulation and a free market economy, while Latinos who are in the service industry may vote Democratic. That was the case for Nevada, where there are many Latinos of Mexican descent and a strong labor union presence, Rouse said.

Race and religion can also play a factor, Guerrero said. Latinos identify in a variety of ways: Out of the nearly 60 million Latinos in the United States, which makes up almost one-fifth of the U.S. population in 2020, about 40 million identify as white, almost 1.5 million identify as Black, more than 220,000 identify as Asian and more than 620,000 identify as American Indian, according to CNN. Their race means that they have different life experiences, Guerrero said, which may lead them toward the right or the left.

[UMD hires coordinator for immigrant and undocumented student life]

And religion can similarly impact where Latino voters gravitate. For instance, many Catholics may see abortion as immoral, which could drive Catholic Latinos to vote for a candidate who opposes abortions. But though the majority of Latinos are Catholic, many are evangelical protestants and small percentages practice various religions including Judaism, Buddhism, Mormonism and Orthodox Christianity, according to Pew Research Center.

But the Democratic party often takes the Latino vote for granted, the three professors said. And when the party does talk to the community, it’s often only during an election year.

“When it comes to grassroots organizing … the Democratic party has not done a very good job of acknowledging,recognizing or supporting those efforts that, time and time again, end up helping them win these elections,” Mirabal said.

The party does very little organizing or coalition-forming with organizations that do the groundwork, Mirabal said, such as Living United for Change in Arizona. The Arizona-based organization launched a “BLUE vote” initiative in which they mobilized Latino voters, Mirabal said. The Democratic party needs to support these organizations with funding and with consultants, Mirabal said.

Additionally, some immigrants who are naturalized or become citizens can feel disconnected from American politics, Guerrero said, and are not informed about the larger political landscape. They don’t necessarily think their votes matter, and that’s partially because parties don’t do enough outreach to these communities, she said.

The votes of Latinos could have been more decisive in the election, Guerrero said, if both major parties had reached out more to them.

“They’re an untapped source of power,” she said.

In this election, it seems like Biden might have focused on the Rust Belt states rather than Latino communities, Rouse said. But the Latino community is growing and expanding throughout the country.

“I don’t think we can ignore them as a political or electoral strategy in the future,” she said.

In her view, Biden did not necessarily earn the vast majority of his votes, Guerrero said.

“People are aware that Trump’s policies would be much more detrimental,” Guerrero said. “Campaigns need to pay attention to everybody, all kinds of Americans with different issues.”