On an alarming piece of red paper, one flyer from the punk scene in the early 1990s reads, “The revolution starts here + now / within each one of us.”

“Burn down the walls that say you can’t,” is underlined below it. In a list that follows, the sign reads, “Resist the temptation to view those around you as objects + use them … Figure out how the idea of competition fits into your intimate relationships … Believe people when they tell you they are hurting.”

From Duke Ellington and Marvin Gaye to Elizabeth Cotten and Roberta Flack, Washington, D.C., has long been home to musical excellence. And now the history of punk rock in the nation’s capital is on display at the University of Maryland.

Special Collections in Performing Arts — or SCPA— at this university presents a new digital exhibit exploring the first 15 years of the punk subculture in Washington, D.C. Persistent Vision: The D.C. Punk Collections at the University of Maryland displays more than 1,000 digitized flyers, photographs, zines and recordings from SCPA’s collections of Washington, D.C., punk archival material, John Davis, an SCPA curator, wrote in an email.

The exhibit, co-curated by Davis – a longtime participant in Washington, D.C., punk bands – and musicologist and SCPA manager Ben Jackson, displays rarely seen artifacts from the subculture through narrative essays and discographies framed within the historical happenings in the U.S. and its capital from the late 1970s to early 1990s.

[UMD Dunkin’ fans remain loyal despite controversial rewards program update]

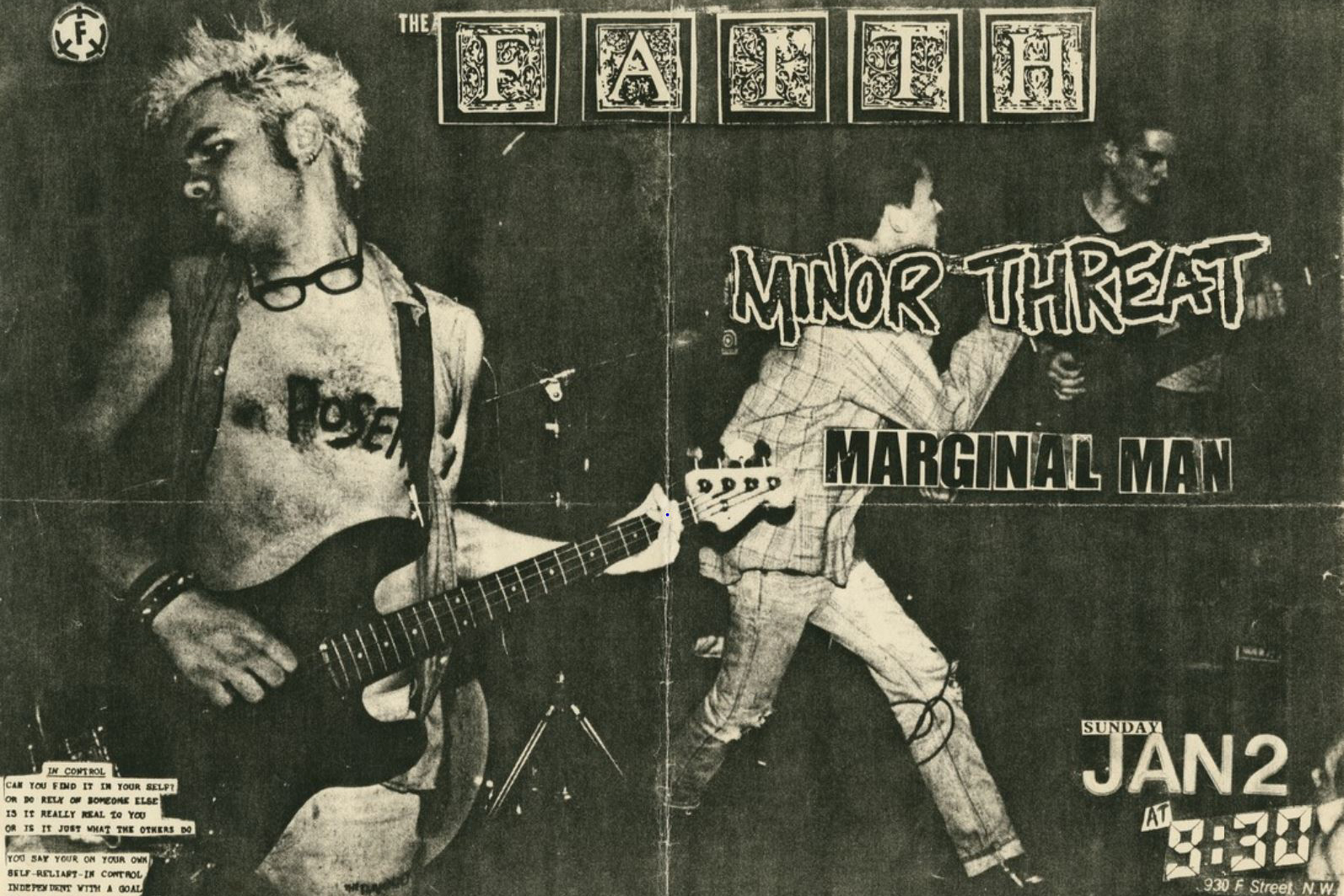

With details of the political and cultural events occurring in the community each year, the exhibit illustrates the rise and explosion in popularity of influential Washington, D.C., punk bands such as Bad Brains, Minor Threat and Rites of Spring, while also spotlighting overlooked contributors including fanzine creators and record label owners.

As a living exhibit, Persistent Vision will continue to add scenes from the punk community in the 21st century in the months ahead.

Punk rock was mostly born in New York City and London, but it quickly flowered in Los Angeles, San Francisco and other cities as places sought to reconnect rock music with the grit and subversion of its earlier years.

The district was a troubled place in the 1970s, wounded from the damages of the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, systemic racism, civil unrest and bureaucratic mismanagement. But after the election of civil rights activist and Washington, D.C., city council member Marion Barry for mayor in 1978, the district saw signs of hope, and residents embraced optimism.

While Washington, D.C., continued thriving as a hotbed of innovation in jazz, folk, rock, R&B and bluegrass communities, two new genres arose and became just as synonymous with the city’s cultural identity.

Trailblazers including Chuck Brown and Trouble Funk gave way to an electric blend of funk, hip-hop and Afro-Caribbean sounds known as go-go. Themes of self-sufficiency rooted in go-go were echoed in the arrival of punk rock and its spirited response to the musical and cultural inertia of the U.S.

Stylistic boundaries were pushed and activism intensified as bands such as the Sex Pistols, based in England, and Black Flag, based in California, rattled institutions to inspire youth to challenge everything around them.

[Review: ‘She-Hulk’ broke the Marvel canon for all the wrong reasons]

Groups such as the Slickee Boys and Overkill were some of the first punk bands to emerge in the Washington, D.C., scene , giving way to rapid growth in the genre and its dynamic push forward for more than 45 years.

A photograph of Howard Wuelfing and Marshall Keith of the Slickee Boys around 1978 is included in the exhibit. The men rock on their electric guitars with their legs spread out, hips thrust forward and lips puckered or bit in concentration.

The following decade was a turbulent time for the capital. Ronald Reagan won the 1980 presidential election and his administration’s social and economic policies quickly turned into fuel for youth rebellion.

The punk artists protested against the administration throughout the decade with music, visual art and activism. Flyers took on a more cynical tone, with skulls, a middle finger and one man, dressed in a suit with a landline phone in hand, sitting with a target over his face.

“I’m no subject, what about you / I got my rules, I don’t need you,” one flyer reads. “I wear the uniform of my own choice / Listen to no one, I got my own voice.”

Bands spread these messages across the university’s campus too. From the Varsity Grill on Route 1 to Stamp and Ritchie Coliseum, the University of Maryland and the greater city of College Park were important sites for punks to perform.

Despite the city’s unsuccessful attempt to ban punk from its venues in 1979, the flyers and zines document the persistence of punk culture among young, newly self-sufficient students who were ready to use their voices.