Despite bills over the years that restrict Maryland universities from asking applicants about previous arrests and convictions, the University of Maryland has continued to ask its applicants about their criminal history.

In January 2018, the Maryland Senate overrode Gov. Larry Hogan’s veto on a bill restricting colleges and universities from asking applicants about their previous arrests and convictions. But as this university continues to ask the question, concerns come to light.

For high school seniors, the application process can be tedious and overwhelming. The addition of being asked about their potential criminal history doesn’t help.

Leila Faraday, a senior at Montgomery Blair High School, found the college application process included more steps than she anticipated, and she believed some questions were too personal.

“The criminal history questions feel a little bit invasive … I don’t know that that matters so much or it should matter so much for them as they evaluate you,” Faraday said.

Faraday said she believes the criminal history question isn’t always necessary, and she said a student should have space to explain themselves if they did commit a serious crime.

[Gov. Larry Hogan explores options to bring more Asian Americans to UMD journalism college]

Ryan Binder, a senior at Thomas S. Wootton High School, also found his application process to be arduous. And while he didn’t think much about answering the question about his criminal history, he understands how it could negatively impact some applicants even if the university is trying to be safe.

“From the student’s perspective, it is not necessarily the most fair too because it could give you a big disadvantage for a mistake that you made in your past,” he said

While there has not been much research on the topic related to universities, Robert Stewart, an assistant professor of criminology and criminal justice at this university, conducted extensive research on how a criminal history question on college applications affected university admission rates.

Stewart conducted his research with pairs of applicants — each pair consisted of one person with a criminal history and one without. His research found that the applicant with a criminal record was three times more likely to be rejected than the applicant without one.

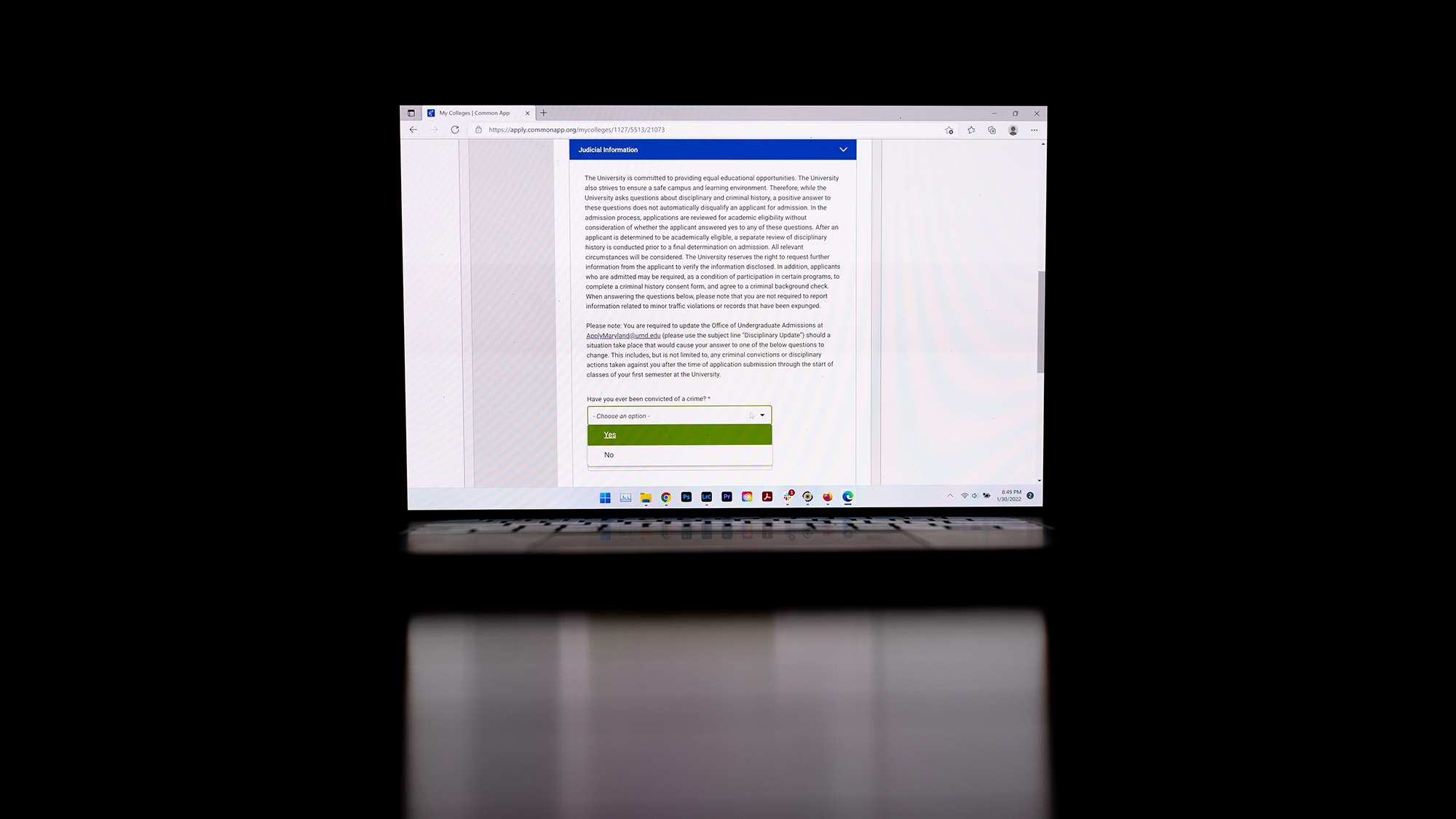

In 2018, the Common Application decided to stop asking applicants about their applicants’ criminal history beginning in the 2019 application cycle, according to the organization’s website. This university decided to add the question in their own questionnaire on the Common App and continues to collect information regarding a student’s criminal history.

The university’s admissions office “takes a holistic approach when evaluating each prospective student application [by] reviewing within the context of their academic and personal circumstances,” according to an email from university spokesperson Hafsa Siddiqi.

Siddiqi explained that if there is a concern about an applicant’s response to the question, they are referred to the Office of Student Conduct where their information is further reviewed. The university may request additional information or speak with the student directly, Siddiqi wrote.

However, it’s “exceptionally rare” that a student is not accepted due to this process, she added.

Stewart believes campus safety spurs the university to assess an applicant’s criminal history — but he said he hasn’t seen any empirical evidence proving that these questions are effective in reducing campus crime.

Additionally, some students who have criminal backgrounds may decide not to apply or choose to apply elsewhere when they see a question about their criminal history, he said.

“There’s no place … where when you report your criminal history to somebody does it really help you,” he said. “It only really causes barriers.”

Although there may not be significant racial disparities in the way employers and universities view applicants with criminal backgrounds, there are still imbalances that exist in the legal system, Stewart said.

[UMD to build the Agora, a community space for people of color in Greek life]

“Some students, particularly young Black males, are more likely to be exposed to these things and probably more likely to have a record,” he said.

The state of Maryland’s population is about 30 percent Black, according to the U.S. Census, while the state’s flagship university hosts only about 10 percent Black students.

In early 2021, Maryland Sen. Obie Patterson sponsored a bill with Sen. Malcolm Augustine to prevent loopholes in college admissions processes that allowed universities to reject students based on criminal histories. It was fully passed in May 2021.

The 2018 bill did restrict universities from asking about an applicant’s criminal history, but it created loopholes allowing universities to consider an applicant’s criminal background through third-party recruiters. The new bill would eliminate that loophole, Patterson said.

As a former parole commissioner, Patterson proposed the bill to “provide greater and more opportunities for those who have a record,” he said.

Patterson said the question on college applications can be hurtful to those who have a criminal history because it puts them at a disadvantage against those who are just as qualified but do not have a criminal history.

“Some do not understand the legalities of a system that has overtly impacted people over the years,” he said. “And they just aren’t comfortable with it and take two or three generations probably to get out of that situation.”

Rodrigo Martinez, a sociology doctoral student at this university, researches how formerly imprisoned men, particularly Black men in Washington and Oakland, California, are civically involved in their communities.

Martinez said the reason people face challenges after release from prison, especially people of color in lower-income areas, is due to the racial disparities already present in American society.

“A lot of this is really about structural changes that need to happen,” he said.

Oftentimes, those who are in prison receive their education in prison or do not receive an education because of the disadvantages they face, Martinez added.

Martinez said removing the question would be a good first step, but Black students still experience discrimination at every level.

To make a significant change, the university needs to “signify that they’re committed to racial equity and the well-being of all its students,” Martinez said.

“[The university] really needs to prioritize students with criminal convictions and also those coming out of prison,” he said.