It was the night after Election Day and President-elect Joe Biden was edging past President Donald Trump in a few key states; the vote was still far from being decided and the entire country held its breath. Some professors at the University of Maryland canceled their classes. The mood across the campus was one of distracted anxiety.

But from 5 to 7 p.m. on Wednesday, 15 students were keyed in— totally and without distraction— to the music.

The UMD Percussion Ensemble, which practices Mondays and Wednesdays, met in person that night, despite the doomy vibe hanging over the nation. They weren’t anticipating the next week, or day, or even hour. For this group, all that mattered was the next downbeat.

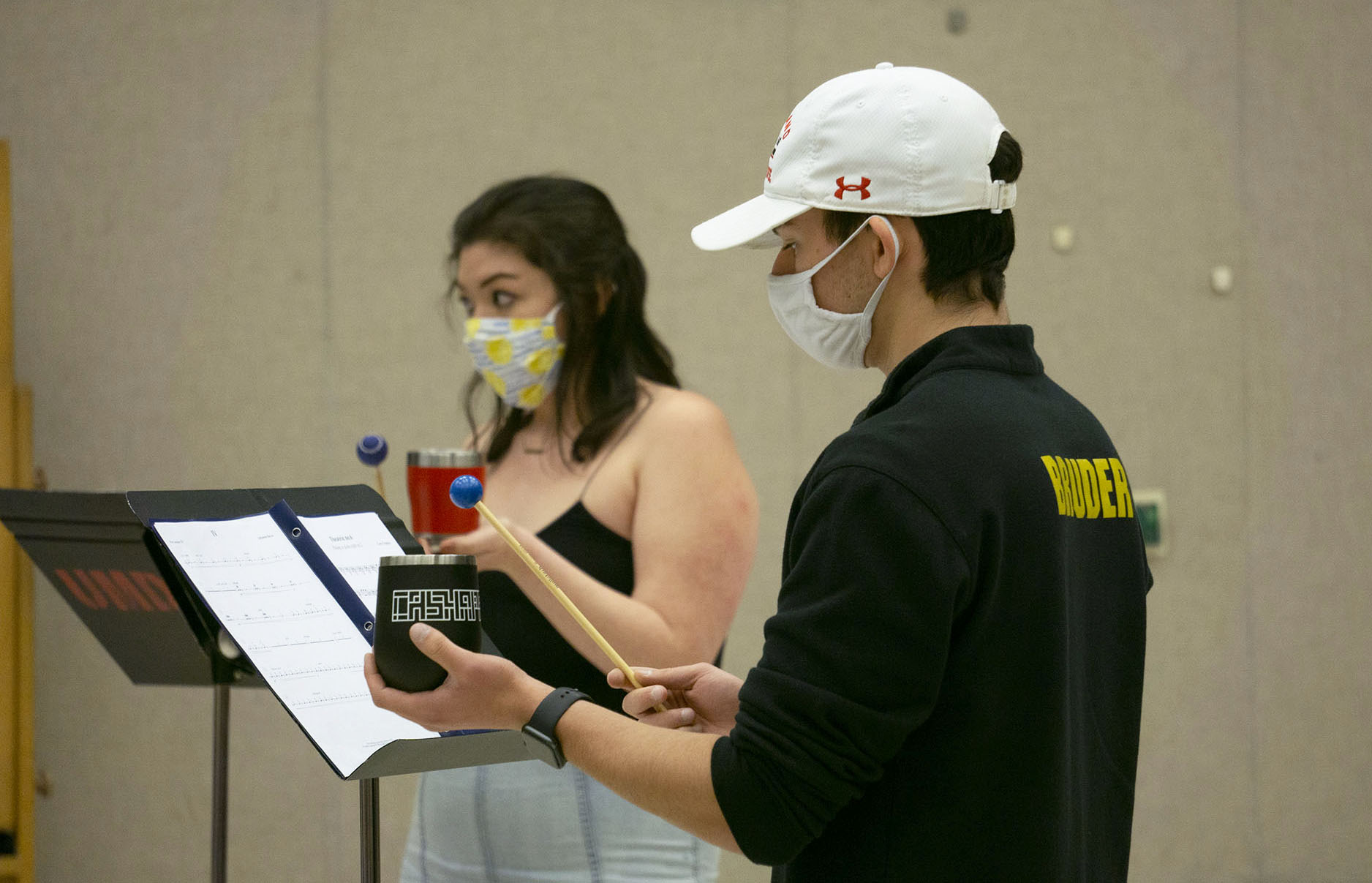

The ensemble was rehearsing a piece called Piru Bole by John Bergamo. Each ensemble plays the music slightly differently; in the UMD Percussion Ensemble’s interpretation, the body acts as a percussive instrument. So on Wednesday night, members of the ensemble were not only beating drums and tambourines, but also snapping, chanting, and stopping every few measures to fix little problems in their performance.

The ensemble has been practicing virtually since the beginning of the semester— but it was only a few weeks ago that the group started in-person rehearsals, said Lee Hinkle, the ensemble’s director.

Percussion players have an easier time with in-person rehearsal than their wind and brass peers. Percussion involves no spit valves emptied onto tile, no gulps of unfiltered air taken before a long note, no instruments to blow into. Instead, masked and distanced around the band room and with two members on Zoom, they’re able to rehearse as a full ensemble. At the end of practice, they flip on a light that disinfects the delicate instruments.

“It’s cool for percussion and for strings because we don’t have to worry at all about aerosol particles,” said Maia Foley, a sophomore working toward a percussion performance and music education dual degree.

In March, Foley and her bandmates, along with the rest of the university’s classes, went remote. Zoom lag has made it challenging for many classes to run smoothly — but for music classes, which require millisecond-level precision, productivity is very difficult.

“Over Zoom, the sound delay is ridiculous,” said Jada Twitty, a fifth-year senior percussion performance major who will graduate this fall. “There’s no way to really play together and hear everything come together.”

Now together again, the ensemble has mostly been catching up with the music — and with each other.

“We’ve been in quarantine for seven months and I have missed people so bad,” said Twitty. “So just being able to see their lovely faces and talk to them … it’s just so nice.”

[Review: Ariana Grande’s new album is just alright, and that’s OK]

On Wednesday, the feeling of closeness between the members of the ensemble was palpable. Twitty and a few other students sat in a clump of chairs on the left side of the room, exchanging familiar glances and giggles during breaks in the music. The whole ensemble — save two students who Zoomed into the rehearsal from their homes — was physically present. The voices of different members popcorned around the room, trying to solve this little problem in timing or that little hiccup on a syllable. No one directed; Hinkle was facilitating the conversation, but not dictating it.

This kind of collaborative, problem-solving attitude is a trademark attitude of percussion players, Hinkle said.

“You don’t actually have to snap with your other hand,” said John McGovern, a doctoral student in a tan flannel shirt, to Devon Rafanelli, a sophomore in a faded tie dye T-shirt and silver-bottomed tap shoes who was having trouble snapping during the piece. “Just look like you’re snapping,” he told her.

McGovern is a second-year doctoral student in percussion performance. He studied the same thing in graduate school and as an undergraduate student. McGovern has been playing since the fifth grade, when he started on the drums. This past summer was the longest he’d spent rehearsing without an ensemble in a decade, and without percussion equipment that he would usually have access to at the university. McGovern said being without a group was difficult.

“I spent a lot of time working on music that was very non-percussion and very non-classical,” McGovern said. “Even though I enjoyed doing that … there’s still a kind of sourness to the fact that ultimately I was just trying to fill the day up.”

McGovern has spent much of his life training to one day be part of an orchestra — but the pandemic has put those goals on hold. Now, McGovern is realizing that his future may take a different path.

“No orchestra in the world is hiring people right now,” McGovern said. “And I don’t see any sign of that changing anytime soon.”

For many of these percussion players, who previously filled their time with private lessons, outside gigs and long hours lounging around The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center between rehearsals and classes, everything has changed. They can no longer spend every day playing with other musicians in person. But for some, that scarcity has engendered a new appreciation for making music.

“I feel like when we came back, the excitement of being with one other sort of charged our playing,” Foley said.

Foley has had chronic tendonitis in her right wrist since 2018; she’s had to compensate for the injury by favoring her left wrist. Foley said in the past, she resented the way the injury affected the music she could to play. Now, having spent time practicing on her own, she’s happy to be in the room.

“I get to go sit in a room where people are playing instruments; I get to take advantage of this rest and I get to listen to other people play; I get to watch other people’s hands and how they’re playing their instruments and I get to learn from watching other people play,” Foley said.

Jonathan Sotelo, a first-year graduate student majoring in percussion performance, echoed Foley’s sentiments. He got his undergraduate degree at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and hadn’t met most of the members of the ensemble in person until these past few weeks.

“It’s just nice to be able to put faces to the names that were on the computer,” Sotelo said. “And music just becomes so much more fun when you’re around people and can feed off of everyone’s energy.”

At about 6:45 p.m. on Wednesday, some of the ensemble left for the night. The remaining members spread into a wide circle in the center of the room, and McGovern placed a recording device in the middle and gave a brief rundown of the plan. A nine-person group would record another piece, IV, two or three times tonight; later, they would layer the recording over a music video. It was important to remain silent at the end of the piece, McGovern explained, so that he could cancel out the ambient noise in the room when he edited the file later.

Each member of the ensemble held a mallet and a water bottle or metal cup. McGovern started the recording, and within seconds, all shuffling ceased. The ensemble began to play. A gentle overlapping of bells spread through the circle, increasing in volume until it stopped, leaving McGovern to act as the lone metronome. And then: silence. No one moved. Not even to take a breath.

Then they played it again. And again. The pursuit of musical perfection continues, even when the fate of the country hangs in the balance.

“I think the best way to deal with the current political situation is to make music,” Hinkle said.

After Thanksgiving, all classes, including the ensemble’s rehearsals, will go online. Until then, members find comfort in the music.

“It’s an emotional release for me sometimes,” said Twitty. “Sometimes it can be hard for me to convince myself to actually go play — but once I do, it’s just such a stress relief. This is something that I know how to do.”