The usual bustle of car and foot traffic did not appear on Knox Road on the afternoon of Sept. 10. Instead, a deluge of water barreled down the street after a flash flood precipitated more than four inches of water in less than an hour.

Some University of Maryland students, seeing the opportunity for a midday swim, crept out of their rooms and onto the streets. But for other residents, the downpour was anything but fun: basements filled with sewage, water damage destroyed cars and university buildings flooded.

Located in a floodplain just 69 feet above sea level, College Park has been historically prone to flooding. But in a rapidly developing city with aged infrastructure, an increase in impervious surfaces and a lack of bureaucratic accountability, residents are finding themselves in the middle of a drainage problem that has been continually neglected.

Matt Sawyer, a Calvert Hills resident, wasn’t at home when the Sept. 10 flash flood swept through College Park. When he received a call from the tenant who rents out his basement, he learned that water from the sewage system was coming up through the downstairs drains.

Water rose up about calf-deep, causing considerable damage to his furnace, water heater and finished basement walls and trim, Sawyer said. Virtually everything his tenant owned, except for her hanging clothes, was damaged or ruined, and had to sit in plastic bags outside of the home while she stayed in a hotel.

“She’s actually probably the one who has suffered the most,” Sawyer said. “And I feel for her because I can’t give her any direction. I don’t really know what to do.”

Normally, when sewage surcharges occur in Prince George’s County, the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission will assess whether the backup is the homeowner’s responsibility or WSSC’s responsibility. If it’s the latter, the homeowner must make a damage claim in order for WSSC to cover any expenses.

Calvert Hills resident Aaron Springer, who has lived in College Park for the past 20 years, saw his car drown after rainwater rose to about knee level during the Sept. 10 storm.

While this incident wasn’t a sewage issue, Springer said WSSC has actively denied damage claims in the community over the years. Last time Springer’s basement had a sewage backup, WSSC paid for the cleanup but not the damage claim, instead deferring responsibility to the county and Springer himself, he said.

“I think that they’re not ready to take full accountability for their storm or water management,” Springer said. “It’s crazy.”

[As water pooled into UMD’s Hillel Center, students braved last week’s storm to come help]

However, discerning responsibility for water damage means differentiating stormwater management from freshwater or sewage management.

Right now, Prince George’s County is responsible for any stormwater management infrastructure, whereas WSSC — which serves as a public utility — is responsible for “maintaining the individual water service from the main to the property line,” according to its website.

In other words, the infrastructure from the property line to the resident’s house is not WSSC’s responsibility, but rather the homeowner’s. This caveat has allowed WSSC to deny homeowners’ claims, since sewage backups in Calvert Hills can, upon investigation, be caused by the inadequate infrastructure that runs from the property lines — where WSSC’s responsibility ends — to the homes.

Jerry Irvine, a WSSC spokesperson, said every incident is assessed on a case-by-case basis. When residents call, a claims inspector will visit their homes and determine whether it’s a sewage backup. Usually, Irvine said, brown water is an obvious indicator that it came from the sewage pipes.

But when there’s a flash flood, it’s typically the stormwater drainage that gets overwhelmed, which the county is responsible for, Irvine said. Sometimes excess rainwater can get into WSSC’s system, but it’s often stormwater that floods people’s homes, he added.

Nevertheless, District 3 council member John Rigg said sewage backflows have been and continue to be a problem for residents as a result of flooding.

Rigg said he sent out a survey to residents of Calvert Hills and Old Town after the Sept. 10 storm and found that out of the 49 households that responded saying they experienced flood damage, 24 of them said they had sewage backflows.

On top of that, Rigg — a resident of Calvert Hills — said he’s experienced four incidents of sewage backflows since he moved into College Park in 2007.

“I have on my phone a picture of my basement drain and my shower, which is in my basement, bubbling up with sewage. That’s a problem. That shouldn’t happen,” Rigg said. “That was not stormwater. That was coming up from the sanitary sewer.”

The city sent a letter to WSSC on Monday requesting the commission pay for certain property damages from the Sept. 10 storm and provide backflow preventers — which can prevent sewage overflows — to residents.

“I hope you agree that residents should not experience these system failures and that the WSSC must work quickly to ensure they do not occur again,” College Park Mayor Patrick Wojahn wrote in the letter. “We expect the Commission to improve its infrastructure so that our residents’ health and safety are not jeopardized during future storms.”

The history of the Calvert Hills and the university’s development can also help explain its ongoing flooding issues.

With old homes like Sawyer’s and Springer’s — built in 1939 and 1942, respectively — the outdated piping system could account for sewage backups when heavy rainfall occurs.

Additionally, Rigg said that when the university built up during the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, no stormwater management was introduced. All of the runoff from storms is instead funneled into Guilford Run near Terrapin Row, which brings the water downstream — underneath Route One, College Park’s neighborhoods and the Metro tracks — and eventually into the northeast branch of the Anacostia River.

When the Metro tracks were first built, Rigg said, a number of storm outlets were covered up, leaving just one narrow outlet available. This has only compounded the flooding problem.

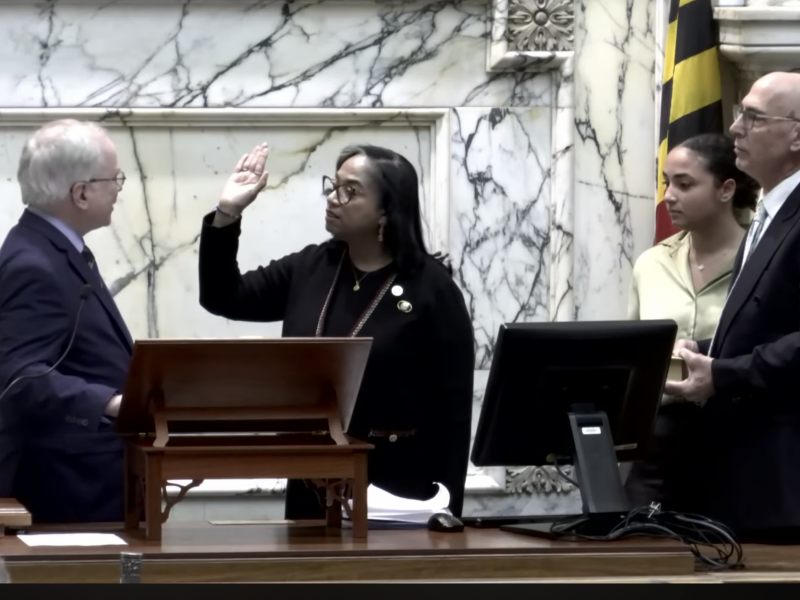

[UMD, Towson tenants join Maryland delegates at state house in fight to terminate leases]

In more recent years, though, Prince George’s County has been working to help Calvert Hills residents.

After a storm in 2009 that generated lots of flooding and property damage in Calvert Hills, the county found that the stormwater drainage system set in place by WSSC — which controlled stormwater management before it was handed off to the county — was never built to the 10-year standard.

This standard determines whether the infrastructure could withstand a storm that’s likely to occur once every 10 years — a type of storm that, with the impending effects of climate change, could occur more often and lead to serious flooding.

In 2013, the county announced a drainage improvement project in Calvert Hills, but the design phase has stretched a span of nearly seven years, to the dismay of many residents. The project is now set to begin this fall and will take about two years to complete.

However, county council member Dannielle Glaros said Calvert Hills continues to have issues with sewage backups, which Prince George’s County is not responsible for.

“I’m not sure why it hasn’t been quite addressed here,” Glaros said. “I think this one needs to be figured out.”

Things can be done from the county’s perspective to mitigate these problems, Glaros said. For one, impervious surfaces can be minimized — whether that entails retrofitting existing impervious surfaces or preventing deforestation for future development.

The proposed Western Gateway Project, for example, could place about 300 apartment units and 81 townhomes for graduate student housing on currently state-owned, forested land near The Domain in College Park.

But with fewer trees upstream to absorb rainfall, the project — which Gilbane Development Company announced has an anticipated completion date of August 2022 — could worsen flooding in College Park.

[Here’s what College Park residents think about students’ return to campus]

Calvert Hills resident Stuart Adams said even though he feels most new developments in the area have a positive impact on stormwater management, since it’s usually old impervious surfaces that are being redeveloped, the Western Gateway Project is unique because of its location.

“When we look at publicly owned land like where the Western Gateway is proposed, we got to be incredibly pointed into looking at ways that that’s a net positive,” Adams said. “There’s already known vulnerabilities downstream.”

However, deforestation for development still doesn’t always mean flooding will be worsened. Glaros said the issue, at its core, comes down to smart stormwater management and environmental design on behalf of the county and the developers.

This could mean installing pervious pavers, such as those found near the Whole Foods in Riverdale Park, or even a green roof, like the one proposed in the Greystar project in downtown College Park.

“Stormwater management is going to be absolutely fundamental to this project,” Glaros said. “I really do believe we can have good development and smart development and smart growth, and make sure that we’re also doing the environmental protection and sustainability.”

And with the looming effects of climate change, which will make intense storms more common, efforts to reduce flooding in College Park may take on a new form of urgency.

Looking at the damage his home sustained earlier this month, Sawyer said he’s especially concerned about future storms.

“The damage is substantial, and who’s to say it doesn’t happen again?” Sawyer said. “It’s obviously a real problem.”

When Sawyer initially moved to Calvert Hills, he wasn’t planning on staying for long, he said. But he and his family ended up falling in love with the neighborhood — and now he wants to keep his house in the family name.

“This is a house that I plan on giving my daughter at some point in the future. I’m willing and wanting to make this as solid for everyone — for her, for me, for future generations, for everyone in the community as well.”