A University of Maryland researcher was awarded a $3.5 million grant this summer from the National Institutes of Health to develop a vaccine to fight Lyme disease.

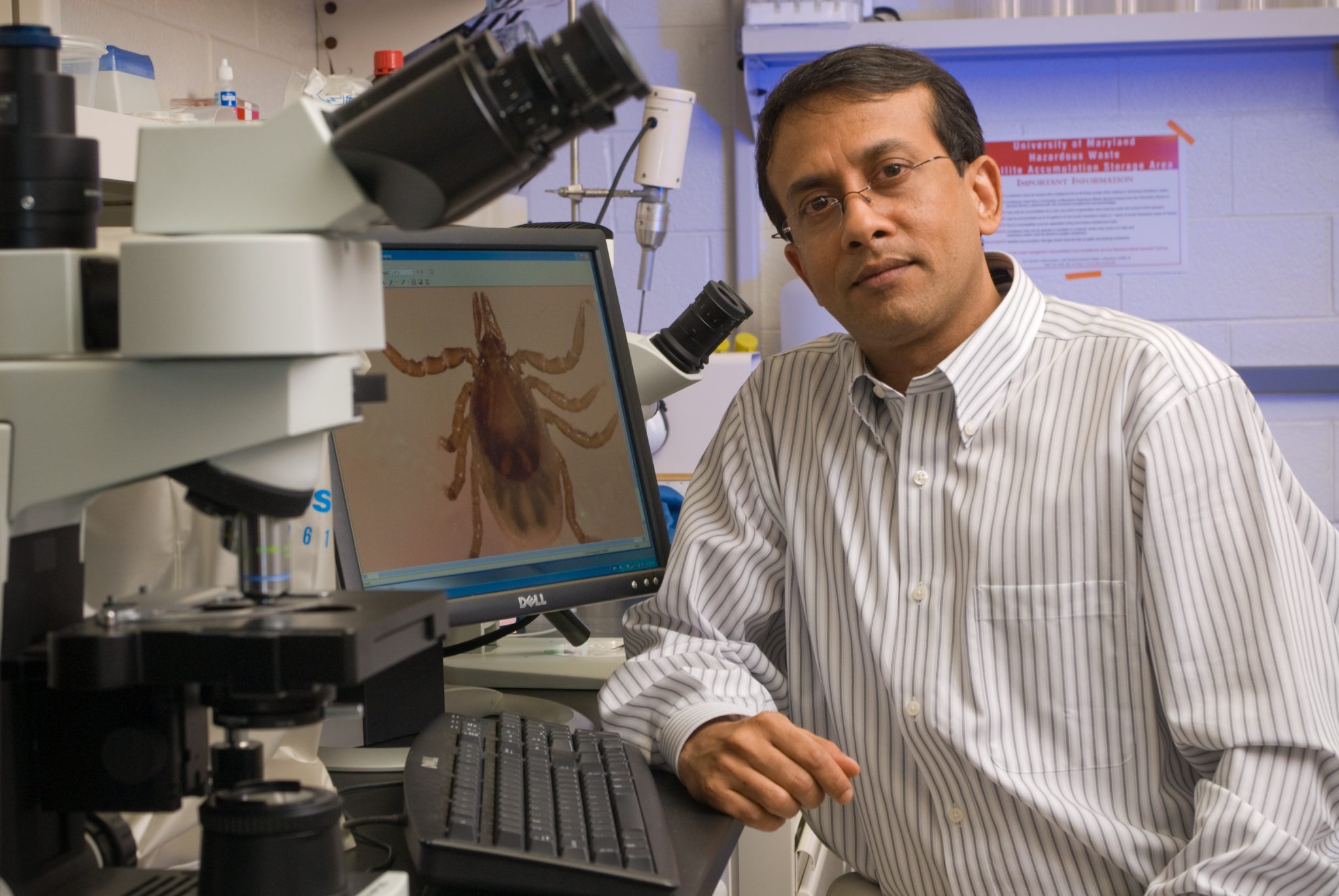

Utpal Pal, a professor in the Department of Veterinary Medicine in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, has been studying Lyme disease throughout his 14 years at the University of Maryland.

The grant, which will be spread out over five years, will connect the expertise that Pal’s lab has with the biological underpinnings of Lyme disease to other researchers who specialize in vaccine development. From 2000 to 2018, the incidence of Lyme disease rose 76 percent from 13 to 23 cases per 100,000 people.

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection transmitted by ticks that is named after the town in Connecticut where it was first discovered. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates around 300,000 people are affected by Lyme disease annually, with Maryland having the 12th highest incidence among all states. Lyme disease can be difficult to diagnose and can cause serious issues, including death, if left untreated.

Pal has spent much of his career studying the molecular biology of Lyme disease. In 2018, Pal was awarded part of a $7.7 million grant over five years to work with labs at three other universities in the U.S. to study the body’s immune response to Lyme disease. Pal said that connecting his research to patient care, called translational science, is an exciting development from this new grant.

“When I trained at Yale, all the people around me were doctors and pharmaceutical representatives. Science translation is a huge thing for me. The basic research we do in the lab has the potential to translate to better developed therapeutics,” Pal said.

[UMD launches interdisciplinary research initiative to support new professors]

As part of this grant, Pal will collaborate with researchers at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia to manipulate the rabies virus to create a vaccine for Lyme disease. The rabies virus is made of RNA, a chemical similar to DNA that can have genes inserted into it so that the body’s immune system protects itself against the protein products of the inserted genes. Pal’s lab will identify which gene sequences from ticks or bacteria cause Lyme disease to insert, then help study how mice respond when given different versions of the vaccines.

“It’s very exciting since it’s a different approach,” said Shraboni Dutta, a graduate student in Pal’s lab.

According to Pal, a few graduate students and other members of his lab will be heavily involved with this grant. Kathryn Nassar, who graduated from the University of Maryland with a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences in 2015, is now the research coordinator for Pal’s lab.

“I went from picking ticks off myself to helping to get to study the ticks,” said Nassar.

The House of Representatives recommended the Department of Health and Human Services, which includes the NIH as well as other health agencies involved with Lyme disease, spend $13 million overall on all Lyme disease projects this fiscal year. Pal’s funding this year — $707,956 for the grant — represents over 5 percent of HHS funding to study Lyme disease.

Robert Harrell, who is the director of the University of Maryland Insect Transformation Facility, said that studying ticks and Lyme disease is less popular than studying mosquitos, which transmit malaria — a much more prevalent disease globally.

[Joining a nationwide race, UMD researchers search for treatment, vaccine for COVID-19]

Harrell is collaborating with researchers at the University of Nevada, Reno, to genetically manipulate ticks. He’s also working with Sanaria, a Maryland-based company developing a vaccine for malaria. While the CDC estimates only 2,000 people in the U.S. each year get malaria, over 228 million people worldwide were believed to have been affected in 2018.

“The world’s deadliest animal is the mosquito that transmits malaria,” Harrell said.

Still, a vaccine for Lyme disease was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1998. But the vaccine was ultimately discontinued by its manufacturer in 2002 due in part to reports of increased side effects that, according to the NIH, were ultimately disproved, as well as lack of coverage by insurance companies. Data also suggested that the vaccine was not 100 percent effective.

Pal said that the rabies vaccine they are using may have fewer safety issues since the earlier vaccine involved administering a single protein from the outside of the bacteria with additives called adjuvants instead of administering a virus like they plan to do.

“From the last 14 years at the University of Maryland we have enough basic information at this point to now take and go to the next step,” Pal said.