There was noise all summer: A string of killings of Black people at the hands of police officers set off protests against systemic racism and violence across the country. But on Wednesday, the sports world fell ghost-quiet.

In the wake of the police shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black Wisconsin man, the Milwaukee Bucks decided not to take to the court for their playoff game against the Orlando Magic. Shortly after, the NBA postponed all matches scheduled for that day. Professional athletes across the country took notice, with more postponements cropping up in the WNBA, MLB and WTA, among other leagues.

The strikes were fleeting; the NBA announced Friday that the playoffs will resume Saturday. But for the University of Maryland’s Black athletes, the gesture was another reminder of just how powerful their platform can be.

“It’s something that’s very eye-opening to other people,” football tight end Tyler Baylor said. “It can’t be ignored.”

“The spectators that are enjoying these sports are the people who aren’t seeing the implications of the actions of the police or … seeing how much it is affecting the Black community,” women’s lacrosse defender Laurie Bracey said.

As conversations about systemic violence and racism against Black people continue, Black Terps are looking ahead, ready to share their experiences in a more welcoming environment than they found when they first came to the campus.

They wouldn’t have it any other way.

“To see some of the guys that I look up to … really doing things to protest and really stand out, it means a lot,” Maryland football offensive lineman Tyran Hunt said. “It inspires me to continue to use my platform, to be outspoken and really be vocal about how I feel about those type of topics.”

[Maryland athletics names Cynthia Edmunds as new diversity and inclusion officer]

For many of Maryland’s Black athletes, these topics — police brutality, voter suppression and misogynoir, among others — have been a regular part of their existences. Not as vague concepts relegated to the back of textbooks and documentaries, but as realities they face every day, experiences that reverberate through their lives and the lives of those who look like them.

Those experiences didn’t vanish once these athletes stepped onto this campus. For many, including Hunt, they served as motivation to do more.

“One of the things I’ve really taken heed of when I first came to college was really using my platform to make changes and be vocal about the things that I believe in,” Hunt said.

Still, it’s proven difficult at times. Despite large swaths of Black athletes turning out for college teams, much of collegiate athletics is still defined by its whiteness.

Then, Ahmaud Arbery happened. Breonna Taylor happened. George Floyd happened. Soon, these discussions — once seen as taboo — were thrust into the national spotlight, and Maryland’s Black athletes responded, speaking candidly about their experiences with systemic racism.

Bracey, for example, has talked publicly about her experience being the only Black player on lacrosse teams she’s played for.

“It’s easy to recognize from an early age that no one else looks like you on the field,” she said. “That’s always been that way for me. ”

[UMD students and alumni fight for anti-racist curricula, culture in area high schools]

But now, in the minds of many of Maryland’s Black athletes, the status quo has shifted. Now, the expectation — for individuals and institutions alike — is anti-racism.

It was a motivating factor in the Big Ten’s decision to establish an anti-racism coalition designed to facilitate communication between athletes, coaches, administrators and officials in the hope of snuffing discrimination out of competition.

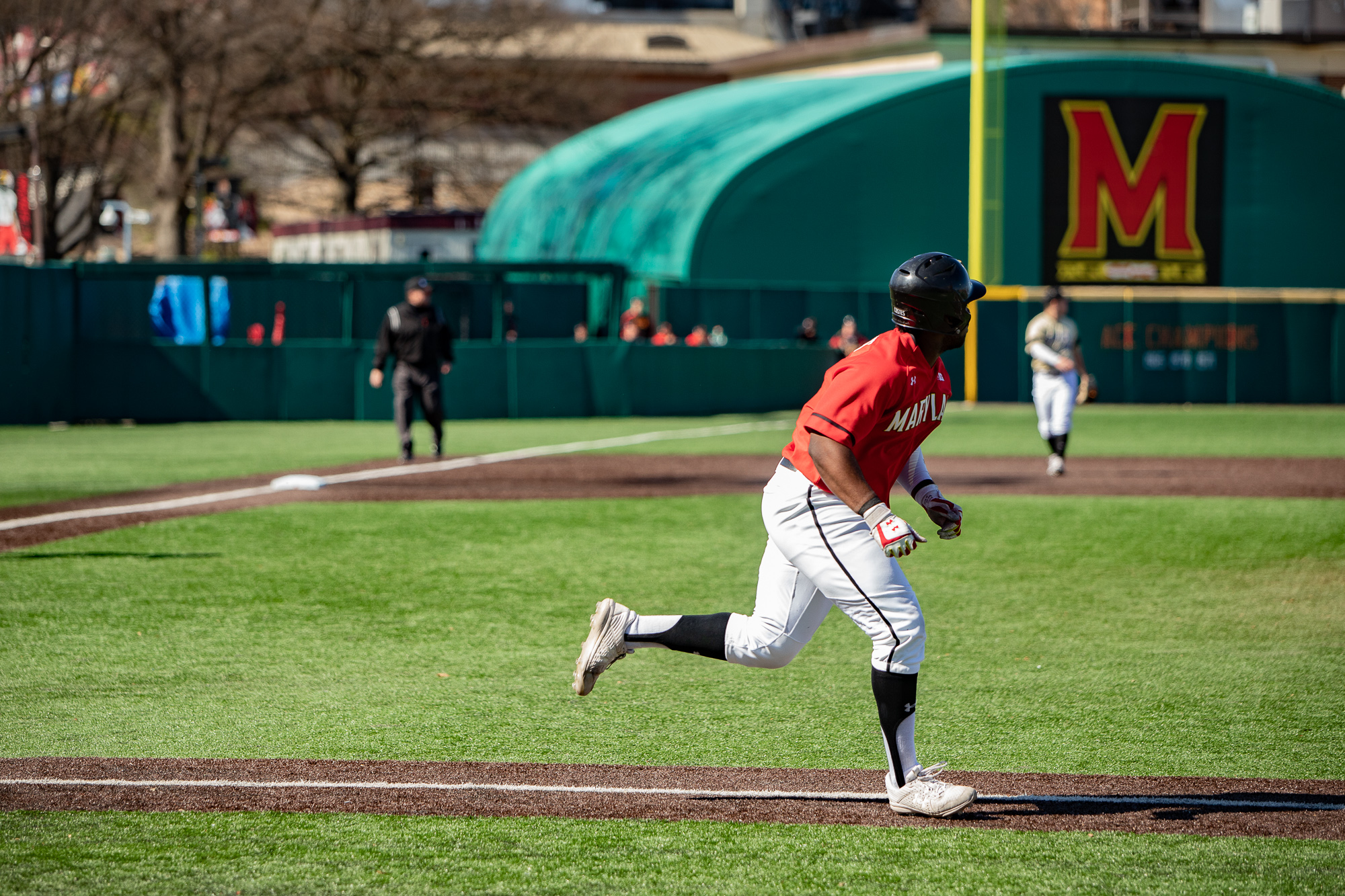

“I [had] to join,” said baseball first baseman Max Costes, one of three Maryland athletes on the coalition alongside football’s Chig Okonkwo and softball’s Taylor Wilson. “I can’t really go out and protest, … I can only do so much on social media than just posting stuff on my story, my writing and stuff. I felt like this was a really concrete way that I could go about doing something for the world.”

Meanwhile, other athletes have used this endless summer as an opportunity to learn about the ways systemic oppression permeates their lives — for their own sake and for others’.

“I’m trying to educate myself to the best of my ability so … I can be knowledgeable about things that I talk about,” Baylor said. “That way I can educate others, educate the younger generation.”

And though Maryland’s fall athletes are currently unable to compete due to the coronavirus pandemic, their pursuit of social justice extends far beyond the playing field. Inspired by the actions of NBA and WNBA players, they are pushing forward in their pursuit for racial justice.

For some of them, including men’s soccer left back Isaac Ngobu, that means vocalizing an oft-forgotten truth: “It is so much bigger than [sports].”