The American Indian Student Union at the University of Maryland is trying to gather support for a campuswide statement acknowledging the university’s campus was built on Piscataway Conoy tribal land.

Although university entities such as the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, MICA and the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center have acknowledged the land already or at their events, AISU members say it’s not enough. In addition to an official, campuswide statement, they also want the university to install plaques and signs across the campus.

“We’re going to students,” said Jazmine Diggs, an executive board member of the AISU. “We’re bringing awareness of where we are.”

The effort began in October, after members of the AISU attended the Big Ten Native American Conference at Indiana University. There, they met native and indigenous groups from other Big Ten universities, some of which had seen much more progress. Indiana University, for example, has a First Nations Education & Cultural Center, dedicated to helping Native American students.

Inspired by the students at other institutions, Diggs and other AISU members wanted to spark a conversation about American Indian representation on the campus. So, after the conference concluded, Diggs started to plan a petition. It launched about two weeks ago, and had garnered about 28 signatures as of Thursday night.

“UMD just hasn’t started this process at all,” she said. “And the biggest problem is that the student body doesn’t even know.”

While the majority of other Big Ten universities start this process by crafting land acknowledgment statements — a formal declaration saying an entity respects and acknowledges the history of American Indian tribes and the areas they resided in — with tribal elders, the AISU wanted to take the issue to students first.

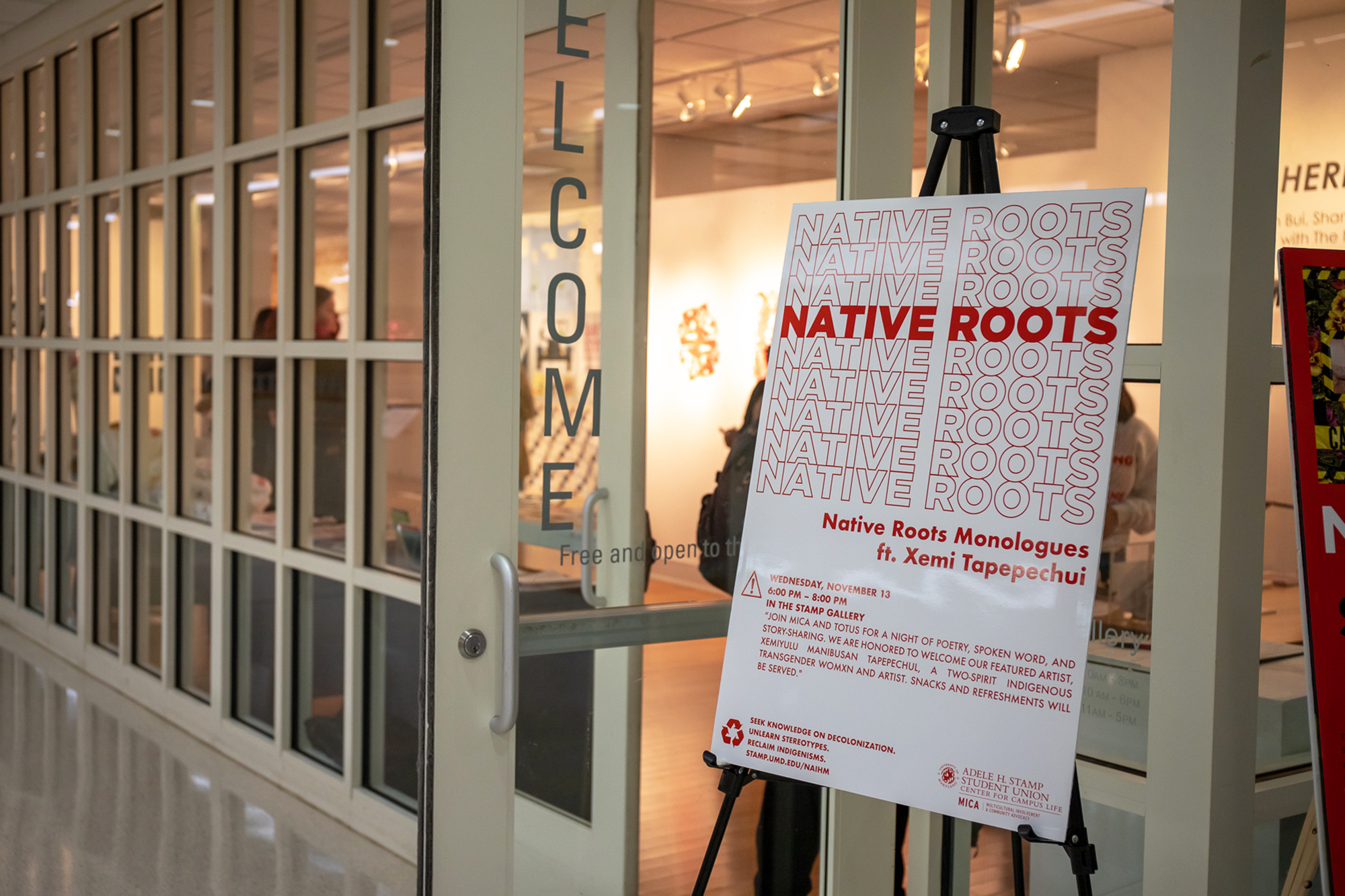

The group plans to collect signatures from students at different events it’s hosting for Native American Heritage Month. Then, members will take the petition to elders from the Piscataway Conoy tribe to create a land acknowledgment statement, which will later be presented to the administration.

[Read more: UMD SGA again votes to advocate for permanent undocumented coordinator position]

As of fall 2019, 30 undergraduate students identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, down from 33 students in fall 2018, according to the Office of Institutional Research, Planning and Assessment. Out of an undergraduate population of slightly over 30,000 students, these students make up less than one percent of the student body.

Despite low enrollment trends among indigenous populations, AISU’s co-president Isabelle Wilson found that being a part of the student group eased her transition into attending a predominantly white institution.

“While everyone here is from a different tribe, we can all come together in the fact that we are all indigenous,” said Wilson, a junior animal sciences major. “We bring issues to light to the student body about what indigenous people go through.”

[Read more: UMD guidelines preventing threatening, disruptive protests need more enforcement, SGA says]

In fall 2016, ProtectUMD, a coalition composed of 25 student groups, released a list of 64 demands for this university’s administration improved support of marginalized communities. Several of these demands pertained to the representation of the American Indian community both academically and socially, such as the creation of an indigenous studies minor and recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a university holiday. While the university has created the minor, the holiday has yet to be recognized.

Although the minor is currently being revamped, AISU members want to make sure that the university hires professors of American Indian descent who can speak more authentically to native traditions and culture, as well as adding their personal stories.

“If you want to teach somebody about like a minority or about a culture, you want to hear it directly from someone who is of that culture,” said Brenee Butler, a co-president of the AISU and junior studio art major. “You hear the impact that it has on someone — you’re looking into a face of somebody who’s seen this happen … You’re not learning it from like a white professor who just happened to go on a reservation and says ‘Oh, I saw this.’”

In the past, groups such as the Student Government Association and the Graduate Student Government have passed resolutions calling for this university’s administration to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ Day — one of the requests from ProtectUMD that the university has yet to meet.

“We have lots of tribes here present on campus. But all of these tribes still only make up less than one percent of its population. And that’s depressing, that’s kind of pathetic,” said Diggs. “My main goal is to change that and to bring awareness like, ‘Yes, we’re here.’”