Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

Every University of Maryland student is familiar with — or will soon get to know — those last few weeks of hell before finals. That time when final projects and papers are handed out like candy and some professors seem to think their class is the only class you’re taking. For Michelle Moraa, a sophomore government and politics major, the stakes were much higher.

In a brand new environment as a college freshman, Moraa said she “hit a wall” with her mental health. She remembers days when she was unable to get out of bed, especially in the lead-up to finals; the personal and academic stress was pushing her to her breaking point. Another added stressor? The fact that she was running out of excused absences.

The university’s attendance policy states that, for a student’s first medical absence, they can submit a self-signed note to get their absence approved. After that, students must obtain a note signed by a healthcare professional.

This makes sense — the university should discourage absence from class. But this policy also harms some of the most vulnerable groups on this campus. One of these groups is students with mental illness. The policy saddles these students with the stress of accumulating unexcused absences while they struggle to catch up with coursework — and it perpetuates a stigma that students with mental illness don’t have actual medical need.

According to the University Health Center website, 53 percent of students at this university experienced “more than average or tremendous stress” in the past year. The site also mentions that “over the course of an academic year, nearly 1 in 3 students felt too depressed to function.”

These statistics are worrying. Being unable to function due to mental illness is a huge roadblock to doing well in school, and coping with an attendance policy that seemingly delegitimizes mental illness doesn’t help.

On the same website, the health center provides the self-excusal note. Below it is a statement saying the health center doesn’t routinely provide medical excusal notes unless a prolonged illness or hospitalization results in a missed class. This means that even if you manage to get out of bed — a feat that 1 in 3 students said wasn’t possible for them at least once a year — and get to the health center, you likely will not be excused from class.

The students who visit the health center do so because it’s more accessible than commuting to another provider who may more readily write a note. For students who struggle to function some days, it’s obvious that leaving campus to obtain a medical note is not a realistic option. So students with mental illnesses are left in limbo when it comes to obtaining medical documentation to miss class.

This lack of options places even more pressure on students. As Moraa explained, “I didn’t want to open up about my situation because I know some people take advantage of it, and I didn’t want to seem like I wasn’t doing my work because I didn’t want to … one thing that [missing class] did … was that it added the stress of me being really behind on so many things that I have to do.”

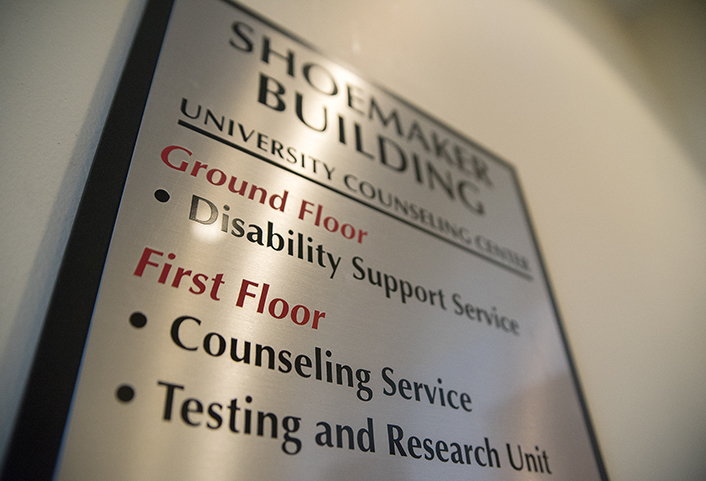

One of the (unadvertised) services the Counseling Center provides is a “Verification of Psychological Disability for Accommodations” form. A medical provider fills out this form and submits it to the Accessibility and Disability Service to request special accommodations for a student. It is unclear if this includes any exemptions from the attendance policy.

Aside from accessing a psychologist, students must have proof of diagnosis — preferably within the last six months. This presents a challenge to those who, like Moraa, were diagnosed years ago. Scheduling an appointment with a therapist at the Counseling Center often requires a discouragingly long wait. Meanwhile, students are still left to fend for themselves when it comes to attendance.

Clearly, there is a gap in support for students who suffer from mental illness. And this gap is further exacerbated by an attendance policy that forces students to jump through endless hoops — some of which aren’t even advertised — to secure permission to miss class.

While it’s important to have a system to discourage arbitrarily skipping class, the university must take into account the growing percentage of its students who may be kept from attending classes because of an illness they can’t control. If the attendance policy exists to ensure students succeed and don’t fall through the cracks, then students with mental illnesses must be accommodated with a realistic alternative that doesn’t treat them like truants.

Though this university might not have a stellar record when it comes to mental health, it must adapt to its students’ needs.

Caterina Ieronimo is a sophomore government and politics major. She can be reached at ieronimocaterina@gmail.com.