Para leer este artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

The Maryland General Assembly is making strides to fix a decades-old hole in state law many activists say harm immigrant families in the state.

Probation Before Judgment lets first-time, non-violent offenders who commit minor crimes plead guilty and receive probation under Maryland law. After completing probation, the offender can move forward without a criminal conviction on their permanent record.

But for immigrants in the state to receive probation, they must plead guilty to a crime, which can lead to deportation or make them ineligible to become a citizen. Because a PBJ plea is a conviction under federal immigration law, it can trigger detention and deportation for non-citizen Maryland residents.

Janice Alonzo is part of one immigrant family facing the strain of Maryland’s PBJ law. The senior academic adviser and adjunct faculty member at the Community College of Baltimore County has a family member that is a DACA recipient and received a DUI in 2020.

After Alonzo’s relative was charged with PBJ, he completed alcohol counseling, took responsibility for his actions and has been working to pay the court-ordered fine, Alonzo said.

[Proposed Maryland bill would restrict biometric information collection]

But every day, Alonzo and her family worry the PBJ could lead to his deportation.

“This family member and the rest of our family treat every day as special in case his days in the U.S. are numbered,” Alonzo said during a Senate Judicial Proceeding Committee hearing in February. “We’ve cried and are very worried about the fact that this family member could be sent back home because of his one-night mistake.”

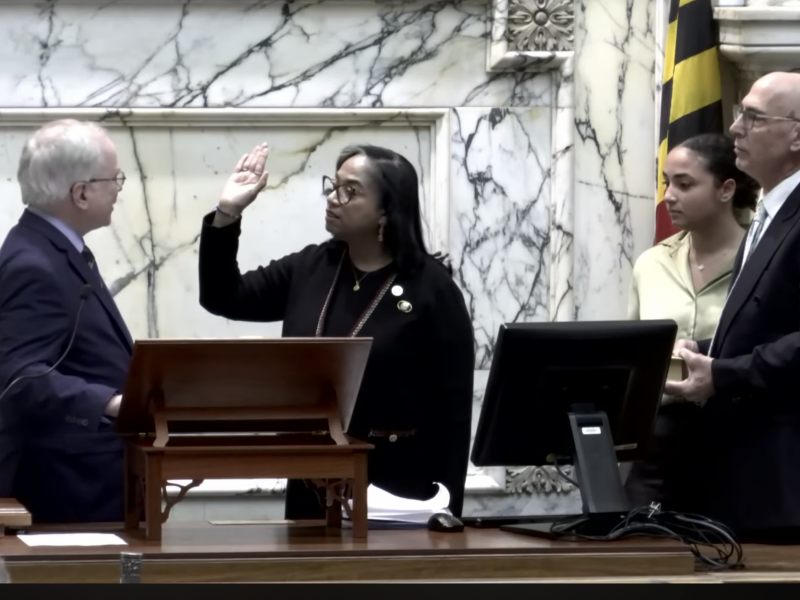

Alonzo testified before the Maryland General Assembly’s Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee and the House Judiciary Committee in favor of legislation titled Probation, Not Deportation. The bill, sponsored by Sen. Susan Lee (D-Montgomery) and Del. Wanika Fisher (D-Prince George’s), would amend the PBJ law to make immigrant communities less vulnerable to consequences of first-time offenses.

“This bill corrects a major inequity and a cruel, unintended consequence in Maryland’s current probation before judgment law that was never foreseen, nor intended by our legislature when the law was originally passed,” Lee said during the bill’s hearing.

The bill changes the 47-year-old original law by affording a judge the option to grant probation to immigrants without requiring them to plead guilty, Fisher said.

For some student groups at the University of Maryland that devote resources and effort to protecting immigration rights, the bill seemed like “common sense.”

“The U.S. immigration system has so many contradictory laws like this, and this bill is a good, technical fix to achieve justice in an equal way,” said Emily Eason.

Eason is the president and founder of Latina Pathways, a club at this university that advocates for documentation and citizenship for Latinx immigrants. Eason, a third-year senior in the joint Bachelor’s and Master’s of public policy program, added that the 47-year-old hole in the law was ridiculous.

“It’s time to get with the times,” she said. “Immigrants who came here 47 years ago are not the same as immigrants who are coming here now.”

Supporters who testified in favor of the bill at its House and Senate hearings added it promotes racial justice.

Emily Johanson, an attorney on the Maryland team of the Capital Area Immigrants’ Rights Coalition, said 99 percent of the clients she works with who received a Maryland PBJ were Black or brown. Of those, ICE detained at least 53 percent after being involved in the criminal justice system, Johanson said.

“These numbers exemplify the ways that our criminal legal system and its racial discrimination have long served as a direct funnel to the immigration legal system,” Johanson said.

A slew of representatives of legal and immigrants’ rights groups testified in support of the bill during each hearing.

[Maryland General Assembly looks at marijuana, climate, redistricting]

During his testimony before the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee, former Immigration Judge John Gossart recounted how he had to deport a man charged with PBJ for a non-violent offense because he was not a U.S. citizen.

“I did the correct decision, but it was not a just decision. It was not a fair decision,” the retired 31-year Baltimore Immigration Court judge said.

The bill has also been amended in the House and Senate committees. Some critics worried the bill did not make clear that a probation recipient who does not plead guilty still has consequences for violating their probation, Fisher said.

In the amended bill, people who do not plead guilty as part of their PBJ plea still have to consent they would be liable for probation violation, Fisher said.

If passed, the updated law would take effect in October.

With support from the Maryland Attorney General’s office and the Maryland State Bar Association, Fisher is hopeful the legislation she has worked on for four years will pass.

“I think [this bill] took a lot of strength and time to get it to where it is that I think it’s actually in a very passable posture right now,” Fisher said.