Para leer este artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

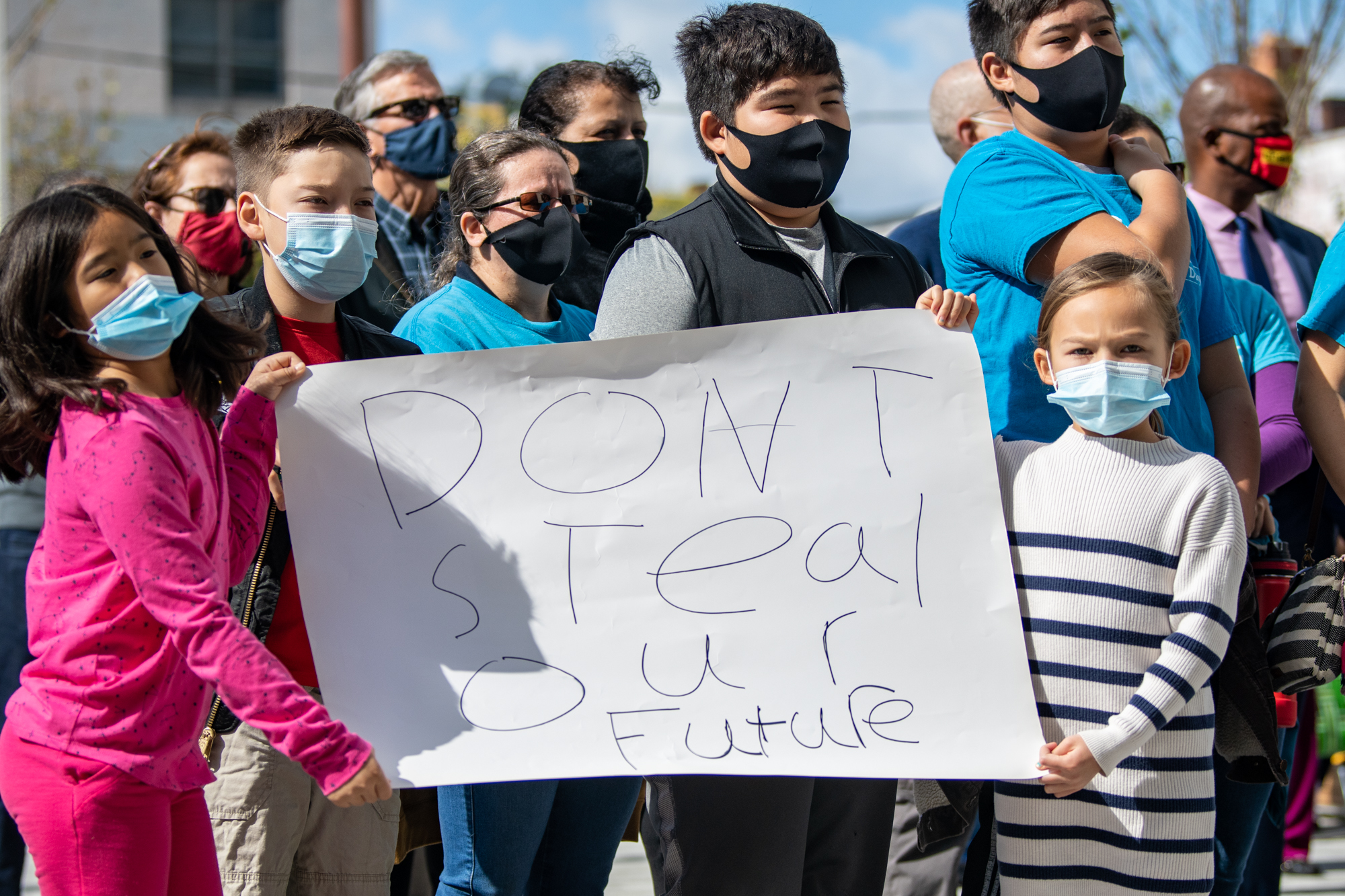

Scores of residents from across Prince George’s County gathered in front of College Park City Hall Monday afternoon to voice their discontent at the county council’s last-minute changes to a redistricting map that would dramatically change how College Park is represented.

The proposed changes introduced at Thursday’s county council meeting contrast with the recommendations of a months-long process conducted by the county’s independent redistricting commission, which held several public hearings on a map that would effectively keep county districts the same. It was pushed to the side when a new map proposing changes to district lines was brought to the table.

The county council voted 6-4 last Thursday in favor of considering the new map, which was proposed by county council member Derrick Leon Davis. Critics argue that new changes were made without any public input, and if implemented, will adversely impact urban communities around the Purple Line for the next decade.

The proposed changes move all of the city of College Park, which is currently split between District 1 and 3, to District 1. Other changes include moving Greenbelt from District 4 to District 3, and moving part of Laurel to District 4. The new proposed map will be officially presented to the county council Tuesday, before a public hearing and a vote in mid-November.

Several mayors in the county, including College Park Mayor Patrick Wojahn, Landover Hills Mayor Jeffrey Schomisch and New Carrollton Mayor Phelecia Nembhard were among the attendees at Monday’s protest.

Later on Monday, the College Park City Council met in an emergency meeting to unanimously pass a motion in favor of sending a letter of opposition to the county council.

For College Park, the changes don’t make sense for the city’s geography, council member Kate Kennedy said. North College Park, which is currently in District 1, is more suburban and more closely related to cities such as Beltsville and Laurel. Conversely, south College Park is more urban and transit-oriented, and benefits from being grouped with cities such as Hyattsville and Riverdale Park in District 3.

[As Prince George’s considers zoning rewrite, community members push for affordable housing]

“It’s also extremely disrespectful that group of legislators — including our own two at-large council members — chose to sign on to a plan that had not been discussed with anybody from this district that vastly changes our representation, and disenfranchises several candidates,” College Park council member John Rigg said. “It’s baffling, it’s disappointing, and it’s just discouraging.”

Wojahn urged attendees to contact the county council, particularly county council at-large representatives Mel Franklin and Calvin Hawkins, who voted in favor of the map.

“This isn’t how a democracy should function, behind closed doors,” Wojahn said at the council meeting. “This is not only going to hurt College Park, it’s going to hurt the county, it’s going to hurt the state.”

Several county council members, including current District 3 council member Dannielle Glaros, were not made aware of the final proposal until Thursday morning — less than a day before the new map was introduced, Glaros said. Maryland Matters reported that Davis said he collaborated on the map with some of his colleagues prior to sharing the map with the rest of the council.

Lan Tsubata, president of West Lanham Hills Citizens Association, came to College Park on Monday afternoon to protest the redistricting changes. She watched Thursday’s county council meeting and felt that council members opposed to the map were “steamrolled,” and if the council members intended on being democratic, they would have opened the process to the public.

“They don’t see us as communities, they see us as commodities,” she said. “We are the commodity of a backdoor handshake deal.”

Those that defend the changes, like Davis, argue the new map would unite municipalities and create a majority-Latino district. But redistricting experts say that Davis’ argument is a ploy to shift criticism from the way that the map may affect the 2022 council elections.

District 2, which would be made majority-Latino by the new map, goes from about 49.5 percent Latino to around 50.5 percent Latino, said Bradley Heard, an attorney and citizen activist. Another citizen activist, D.W. Rowlands, who is also a human geographer, explained that this one-percent difference would likely not make a meaningful difference in terms of elections.

“This is much more being symbolic than anything that actually will affect outcomes,” Rowlands said. “If your goal is to make a majority, a Latino district, you don’t make a whole bunch of other unrelated changes at the same time.”

Several candidates for county council will be affected by the changes, including current District 3 candidate Eric Olson, who will be forced to run in District 1 against incumbent county council member Tom Dernoga. Olson is currently running unopposed for Glaros’ seats in District 3.

“It doesn’t seem coincidental,” said Heard. “It really does not make any sense through any other lens than a political lens.”

[Businesses settle into Discovery District to hire young professionals, promote vibrancy]

The involvement of county council members in the map-drawing process is especially concerning to Kennedy. Small adjustments can and should be made to the map, but not major changes, she said.

“It’s really important to follow an independent commission because you don’t want politicians choosing the people that vote for them,” Kennedy said. “The Davis map, as I’m calling it, divides communities.”

The new map will also be particularly disastrous for the University of Maryland, which benefits from having urban and transit-oriented communities surrounding it, Glaros said. If College Park moves to District 1, it will be represented by Dernoga, who lives in suburban Prince George’s County in Laurel, which is geographically different from urban College Park.

“When you’re making redistricting changes, it’s really important that those proposals are really well-vetted,” Glaros said. “I was disappointed that my public … didn’t really have ample opportunity to weigh in.”

Rowlands argues that these changes are troubling for another reason — it could mean a lack of representation for progressive voters in the county.

“Fundamentally, this is gerrymandering,” she said.

This story has been updated.

Grace Yarrow contributed to this report.