Content Warning: This article discusses sexual assault and sexism, among other discriminatory and abusive behaviors.

Lucy Taylor barely told anyone when the day came for her to leave.

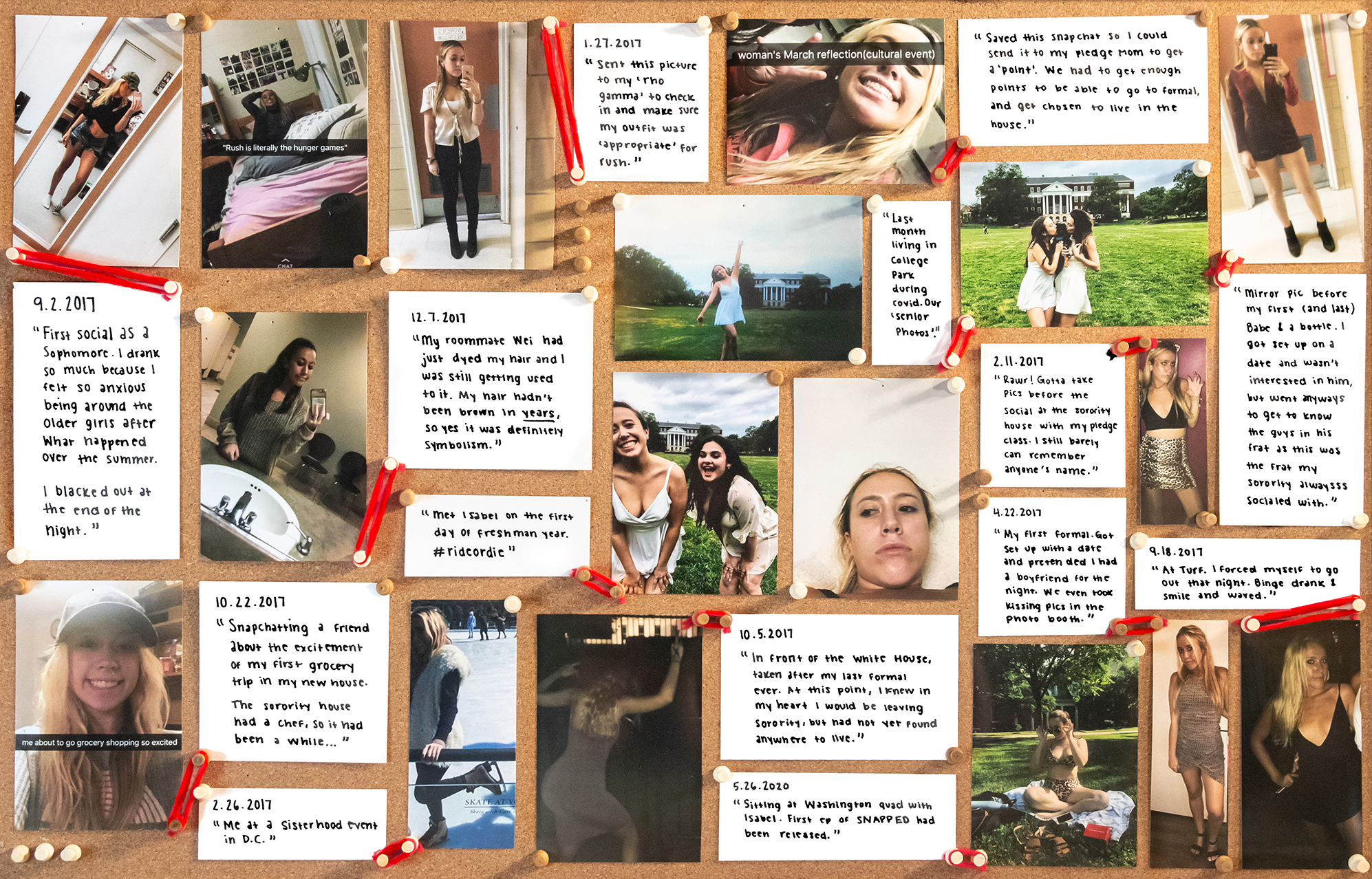

Instead, shaking and unstable, she scurried around the messy room she shared with three other girls, throwing her stuff into boxes — not even bothering to fold her clothes. As she lugged her things to her friend’s car, she tiptoed down the hallways of the house, trying to avoid any conversation or confrontation.

“Freedom! ‘90” by George Michael blasted in the car as Taylor rode away. At that point, she knew: She would never have to return to her sorority house again.

“It was the best seven-minute car ride of my life,” Taylor said in the fourth episode of SNAPPED, a podcast documenting her destructive experience with University of Maryland Greek life. “The only thing that would’ve made it better [would’ve been] if I was naked, with my hands up — and it was, like a convertible. Just, like, giving my middle finger to the house.”

It was October of 2017. Taylor, an alumna of this university, had just disaffiliated from her sorority — an organization she had joined in the spring of her freshman year. But in the six months that followed, she says she encountered rape culture, misogyny and slut shaming.

Three years later, as a senior preparing to graduate with a theatre degree, Taylor launched the first season of SNAPPED, naming it after a term she says her sorority used to slut shame her.

In her podcast, Taylor explains that the word was used to acknowledge when a member of the sorority wasn’t in line with the chapter’s standards. In the months leading up to her disaffiliation, Taylor was “snapped” by her sorority sisters for posting a photo of herself in a bikini on Instagram — forcing her to take the picture down, she said.

For the podcast’s cover image, she used a zoomed-in illustration of the same bikini picture that had caused an uproar during the summer following her freshman year.

Since the podcast’s release, it has been downloaded over 24,500 times on various platforms, including Spotify and Apple Podcasts, and has over 980 followers on Instagram. Now, she’s in the midst of recording the podcast’s second season, which will feature the voices of other students who have disaffiliated or endured trauma from Greek life culture.

Taylor believes the trauma she experienced as a sorority member can’t be explained away by the glib line she has heard over and over — that “Greek life isn’t for everybody.” Taylor wants SNAPPED to help people understand the injustices she says Greek life promotes and consider who the organization is really for.

She wants people to know how racism, classism, misogyny, rape culture and other dangerous, systemic failures are ingrained in the culture, she said.

And the issues entrenched in Greek life persist beyond the University of Maryland. That’s why Taylor waited until the sixth episode to call her alma mater out by name. She also leaves out the sorority’s name since she says it isn’t the only culprit — Greek life as an institution is to blame.

In a statement provided by university spokesperson Hafsa Siddiqi, the school’s Department of Fraternity and Sorority Life said there’s no place for hate or misogyny within the Greek life community. The university is committed to addressing any “culture of silence” that allows intolerance to go unchallenged, according to the statement.

[UMD’s IFC responded to harassment at Black History Month event. Some say it wasn’t enough.]

“We are also working to identify and dismantle any obstacles to participation that exist within our organizations. We advocate for personal responsibility and peer accountability among our members and within the community,” the statement read.

Still, Taylor said she believes Greek life, as an institution, is rife with abuses of power that affect all of its members, particularly those who identify with marginalized communities.

“These organizations are set up for abuses of power. These systems aren’t broken. These organizations are working exactly how they were made to work,” Taylor explained in her podcast. “Count the amount of women of color in your chapter and know that that’s not an accident.”

The start of SNAPPED

At the brink of the podcast’s inception in May 2020, the Abolish Greek Life movement began hitting collegiate communities. As the movement continued, hundreds of students chose to mass disaffiliate — the process of relinquishing all ties to their local and national chapter. The movement largely focuses on abolishing the National Panhellenic Conference and the Interfraternity Council, which are two national Greek life organizations that are predominantly white.

Students across the U.S. shared their stories on social media, advocating for abolishment.

But at this university, the Abolish Greek Life movement hasn’t gained much traction. While the movement exists at this university, it isn’t as strong as it is on other campuses, said Katie May, the president of this university’s Panhellenic Association.

“I have definitely seen trends of the Abolish Greek Life movement on campus,” May said. “Our goal as PHA [is] to try to reduce that idea and to try to encourage people to be a part of something that has a lot to offer, but also does have issues that we’re trying to address.”

When it comes to reporting sexual assault, PHA encourages women in Greek life to “feel comfortable in whatever decision they make,” said Mikaila Baumel, the organization’s vice president of risk management.

“We acknowledge that there may be people who don’t feel comfortable making that decision or don’t want to report a sexual assault … we support them just as much as we support someone who wants to report a sexual assault,” Baumel said. “If someone decides to report a sexual assault, we as PHA exec support them, and we’ll never doubt them, and we’re there for them as much as we can be.”

If Greek life were to be abolished, Taylor said she believes there might be a dip in the number of sexual assaults that occur during the beginning of the academic year, which is commonly referred to as the “red zone.”

During the 2018-19 school year, the Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct received 248 reports of sexual misconduct, and 77 formal complaints, according to its annual report.

“Sexual assault and racism have no place within our campus community, and we will continue our work to create a diverse and inclusive campus that is free of sexual violence,” the statement provided by Siddiqi read.

But these precautions weren’t enough to protect Taylor.

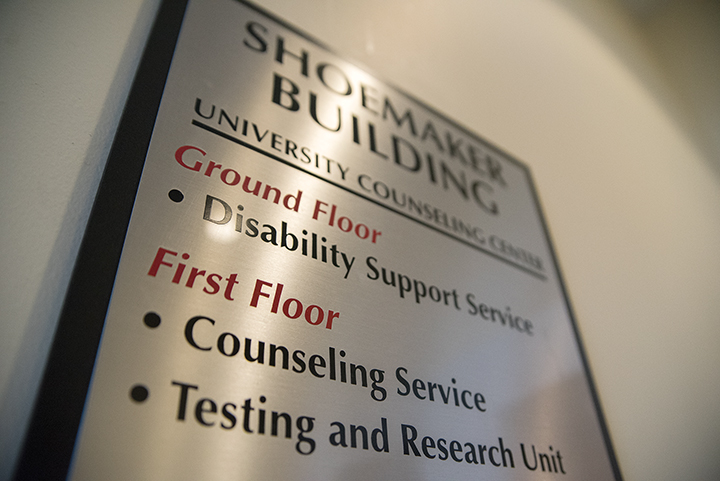

In the podcast’s fourth episode, “ONE IN FIVE,” Taylor reveals she was raped by a new member of a fraternity during her sophomore year. After the incident, it took Taylor a few weeks to come to terms with what happened to her. She wasn’t sure if what happened was actually rape — a common sentiment among survivors of sexual assault.

A few weeks before the incident, Taylor signed up for an intake session with the university’s counseling center. She was anxious over the slut shaming she endured. The incident took place while she was waiting for her appointment date, and when she arrived, she struggled with a slew of uncomfortable emotions after the sexual assault.

“It was the first time anyone had ever validated me and that was the first time it ever clicked in my head, like, ‘Oh shit, you’re right that is rape,’” Taylor remembered.

Emerging from her draining experience in Greek life, Taylor had her doubts about what sisterhood was — she didn’t find it in the very organization that promised its members sisterhood for life.

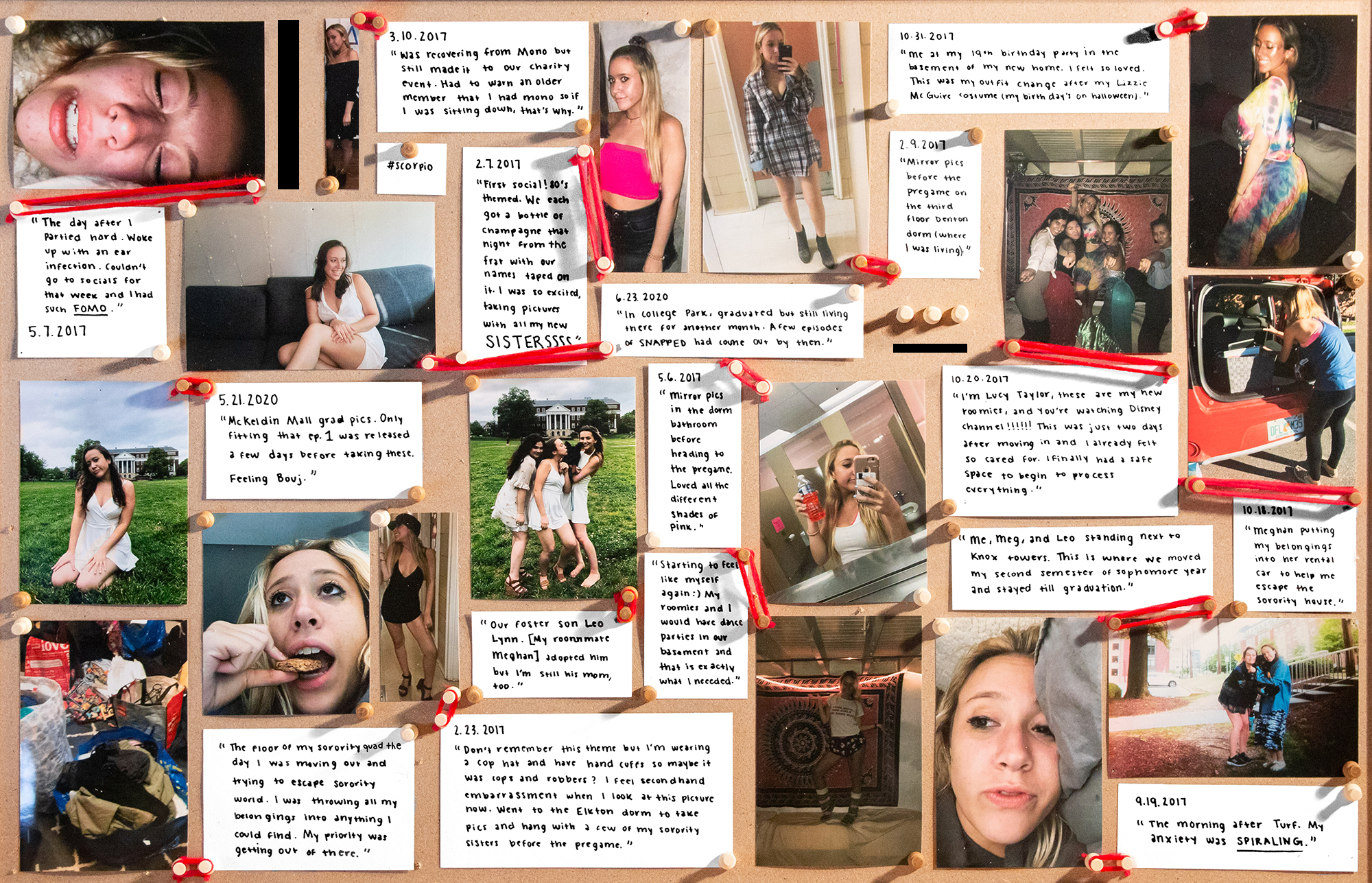

But her friendships with alumnae Meghan Thompson and Isabel Brecher enlightened her to real sisterhood.

They were the ones who helped Taylor when she was moving out of the sorority house, she said. Her roommates in the sorority house didn’t offer any help, she said, which she felt was symbolic to what was going on behind closed doors.

Taylor and Thompson met the summer before their freshman year, but the pair grew distant when Taylor joined her sorority. They reconnected sophomore year, and by then, Taylor was planning to leave Greek life.

Despite only just reconnecting, Thompson supported Taylor’s decision to leave. And Brecher, who Taylor had met on their first day of freshman year, was also alongside Taylor during the healing process. Thompson and Taylor ended up moving in together, and since then, they’ve been inseparable.

“We just kind of became the best of friends from there [and] she still is to this day,” Thompson said. “We have this kind of bond that’s just kind of like the kind of person that you can talk to in your own little secret language.”

Brecher, another one of Taylor’s close friends, explained that Taylor’s passion and unapologetic nature makes her a “force to be reckoned with.”

“Anything she is passionate about, she kind of goes to that extra level to kind of try to make a difference,” Brecher said. “She always kind of brings out the best in everybody, and she always looks for the best in everybody.”

[National Panhellenic Conference opts out of holding a vote on allowing nonbinary members]

Brecher and Thompson worked on some of the technical aspects of the podcast. Thompson helped Taylor craft compelling narratives, while Brecher helped build the podcast’s social media presence.

“They had my back throughout the creation process and they have my back now,” Taylor said.

Shortly after disaffiliating, Taylor said she also faced pressure from her former sisters to refrain from disclosing her experiences in the sorority. Some of the members thought her exposing what happened to her could get the sorority kicked off campus, she said.

Taylor went to the Title IX office because she was told that they had the ability to possibly break her housing contract, she said. But the office was unable to revoke her contract at the time because her sorority was considered an off-campus or private organization, Taylor said.

Taylor also said the Office of Student Conduct reached out to her after someone anonymously sent in her podcast. The office asked her if she wanted to be a part of an investigation — she declined.

“Everything that I want to say is in the podcast,” Taylor said.

One by one, the women — her sisters — who Taylor thought would uplift and support her suddenly dropped out of her life. It started off with cordial glances, waves and small talk, and ended with pretending the other didn’t exist. When Taylor would talk or try to hang out with the friends she made in her sorority, she found that it triggered her.

“I kind of distanced myself from them and slowly started to unfollow anyone that was in Greek life on Instagram because it would just put me in a bad mindset,” Taylor recalled.

In the second semester of her junior year, Taylor began to regularly attend therapy sessions because the trauma she experienced began to take a toll on her social life, she said.

For Taylor, though, a large part of her healing process was creating the podcast as it allowed her “to see the situation for what it is,” she said. And while Taylor believes the healing process goes on forever in some ways, releasing the podcast was “really cathartic.”

Taylor initially recorded SNAPPED as a web series in 2019 telling her story and filming actors retelling other people’s experiences with Greek life.

But as time went by, Taylor realized something was missing from her web series — she needed time to reflect and heal. In the beginning, Taylor would work on the project in spurts, dedicating weeks or months to recording and editing, sometimes taking the same amount of time to decompress.

When she took a podcast production class on a study abroad program in Denmark, she set out on a podcasting journey. Taylor discovered the power that came from voice narration as she began to incorporate storytelling techniques into her recordings. She added sound effects, which she says can transport the listener into the story itself.

“There is just so much cultural silence around the issues that I talk about, and I felt like a lot of people would relate to my story,” Taylor said. “I didn’t really have much control about everything that went down in my sorority experience, and so, I guess I found my power in sharing my story.”

Looking back, Taylor said releasing the first episode of SNAPPED was an “oh my God” moment.

“I couldn’t believe that was possible until I actually saw it up,” Taylor recalled.

And as production continued, she would try releasing episodes when she was hanging out with a friend for support in case anything went wrong or she received backlash. Other times, she would release the episode alone in her bedroom. In either case, she said she felt like she was taking her power back.

“I would kind of just feel like Regina George throwing the Burn Book papers in the hallway … just kind of like, ‘And there it goes, it’s out,’” she said.

Snapped is released

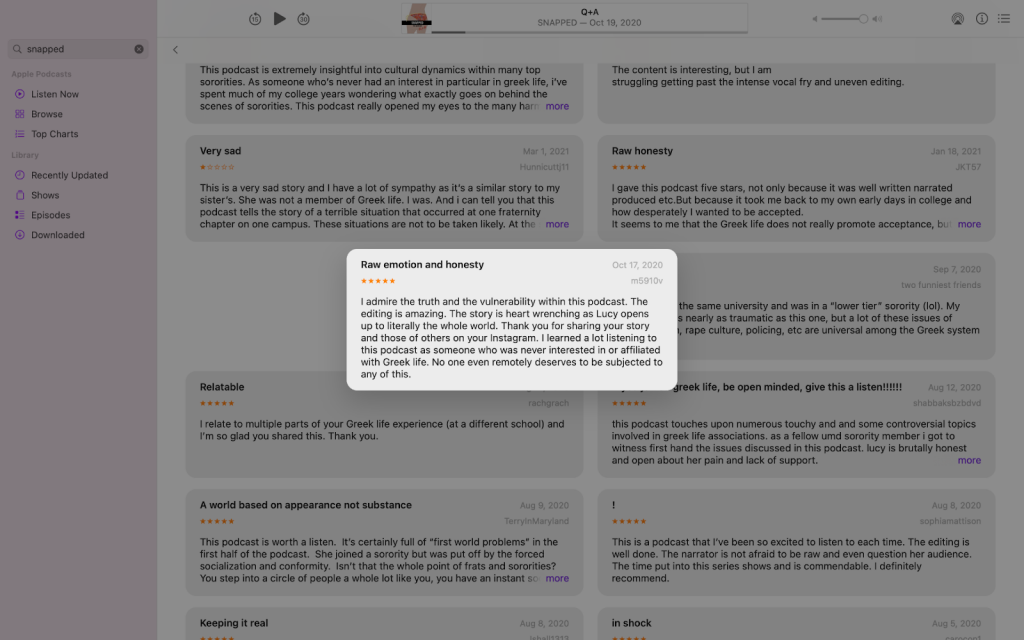

Since the podcast’s release last May, it has received both positive and negative reception from people both involved in and not affiliated with Greek life.

Although some of the feedback was harsh and questioned Taylor’s credibility, she pays it no mind — there’s no point, she said. She explained that she made the podcast to share her side of the story and let other people who could relate to her experience realize that they were not alone. While some comments did bother her, Taylor looked at any hate comments in a “very lighthearted way.”

“At the end of the day when I lay my head down on my pillow, it’s not what I’m thinking about, which is great,” Taylor said. “I’m so much more affected by the love that I get.”

The positivity that stems from reviews and feedback makes it all worthwhile, she said. When the podcast first came out, Taylor was ready for a flood of negativity, but instead, she mainly received encouraging and inspiring messages from others with similar experiences, further validating her own, she said.

“Greek life chapters have been around for so long, are run by elder members, and REFUSE TO CHANGE,” one review read. “This podcast is extremely eye-opening.”

Lizzie Mafrici, a recent graduate of this university who majored in public policy and women’s studies and was president of the student group Preventing Sexual Assault, said she disaffiliated from her sorority around the same time she listened to the podcast.

“I just realized that there’s not a lot of good that can come out of Greek life,” Mafrici said. “As much as I loved my individual chapter, it felt wrong to still be in Greek life.”

Mafrici also took to Instagram to explain why she decided to disaffiliate.

“We all know silence is compliance,” Mafrici wrote in a post. “ It’s time that we recognize allyship that stops at UMD PHA/IFC’s front door is useless.”

Ashley Wells, the vice president of accountability of this university’s Panhellenic Association, said the podcast highlighted a lot of issues they hope to tackle in their term.

“I’ve seen a lot of positive changes that have come out of that podcast,” Wells said. “We’re committed to improving Greek life but that’s in a positive and constructive way.”

Wells added that she met with the executive board of Taylor’s chapter about the podcast and learned that the chapter has made changes to its sexual assault programming. In an email, the PHA president further explained that the chapter also formed a new position on their executive board called the sexual assault prevention chair.

“The best thing you can do as a leader in Greek life is to take negative comments that people have about it and take it as feedback because … If we can’t make Greek life serve everyone, then, you know, what’s the point?” Wells said. “It’s really impressive to see them being able to do that because that’s how we conduct ourselves as we take all negative feedback as positive feedback and use that … to actually address it.”

Baumel also said PHA hopes to implement a requirement for sororities to have a sexual assault liaison who would connect fellow chapter members with resources related to sexual assault. Baumel explained that at the moment, not all sororities on campus have a sexual assault liaison, but she wants to require it of all chapters to ensure access to important resources.

In addition to this requirement, Baumel is also working with the IFC’s vice president of risk management to form a joint committee in the fall that would focus on sexual assault in the Greek life community. She also added that sexual assault liaisons would be a part of this committee.

Season 2

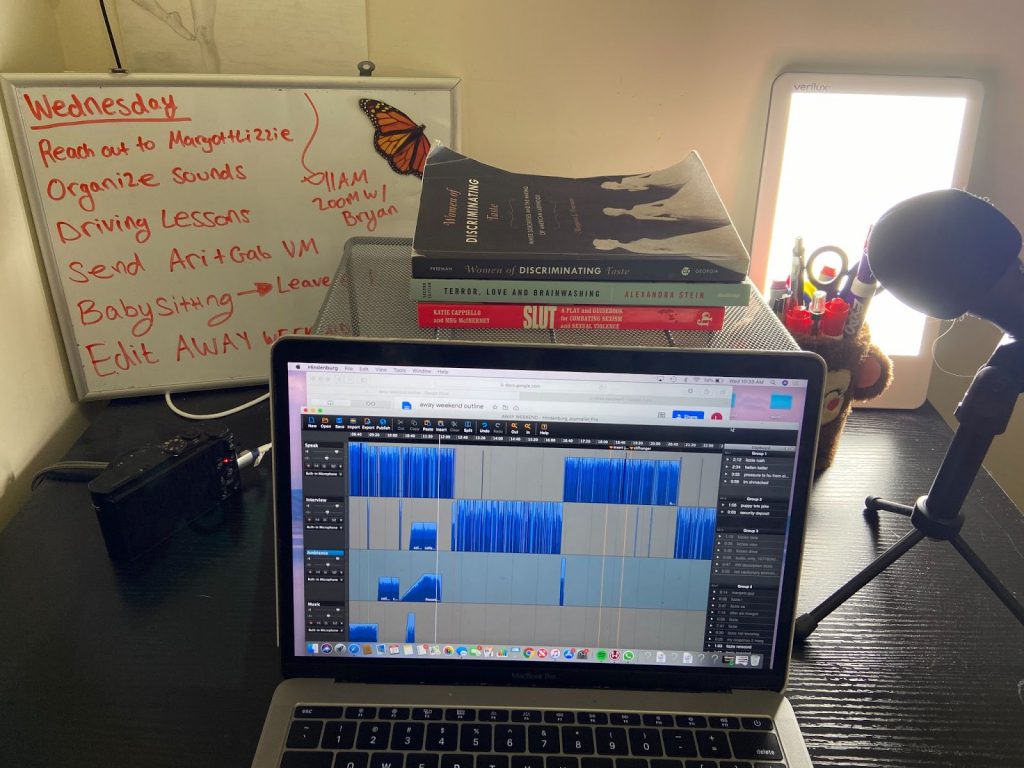

Glued to her swivel desk chair for hours at a time, Taylor’s petite workspace is full of big ideas. A warm, fluorescent white light illuminates Taylor’s face as she edits hours of audio clips down to the most compelling moments. A monarch butterfly magnet adorns a whiteboard that lists her production tasks for the day.

The podcast production process isn’t easy, Taylor explained. It takes care, meaning and dedication to diligently craft a single episode. After producing the first season of SNAPPED, Taylor took a break for a few months, then began recording the second season in November 2020 while also working as a nanny and dogsitter on the side.

Although Taylor doesn’t have an exact date in mind for when the next season will air, she intends to release it sometime this year.

In SNAPPED’s second season, Taylor will examine the history of Greek life and include experts such as Margaret Freeman, author of Women of Discriminating Taste. Taylor also plans to feature other people’s stories on the podcast, ranging from stories about sexual assault to racism to LGBTQ issues.

Taylor also received submissions from listeners who have their own stories to tell on the podcast’s next season.

Alex Smith, a graduated member of a fraternity at this university, will be featured on the second season of SNAPPED. Smith, who agreed to use a pseudonym to protect his identity and safety, offers his perspective as a gay man in Greek life and takes listeners through the harassment he faced throughout his experience.

“Greek life says it's an all inclusive space — it's really not,” Smith said. “No one talks about the bad parts, so I wanted to … just start talking about the bad parts.”

There are similar stories on Instagram accounts calling to abolish Greek life, Taylor said. But she stressed the meaningfulness of hearing the real voices behind the story — listeners can relate to them.

“Even if Greek life didn't fail us in the same way, we still have that common understanding of, ‘That system is fucked,’” Taylor said. “They fucked us over and this needs to end.”

The University of Maryland's CARE to Stop Violence crisis line can be reached at (301) 741-3442. The university's counseling center can be reached at (301) 314-7651. Individuals can file sexual misconduct or discrimination reports through the university's Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct here.