When Emily Lucie’s art classes shifted online last year, she knew where to go for some peace and inspiration: a small forest patch located near the southwestern edge of the University of Maryland’s campus, just west of the business and public policy schools.

The patch, known as Guilford Woods, contains the headwaters of Guilford Run — a creek that empties into the Anacostia River. Lucie said she goes there when she’s stressed; the gurgling sound of the running water and the rustling leaves provide a sense of peace, she added

“It’s definitely great for mental health,” the rising senior archaeology and art history major said.

But parts of the serene site could soon cease to exist.

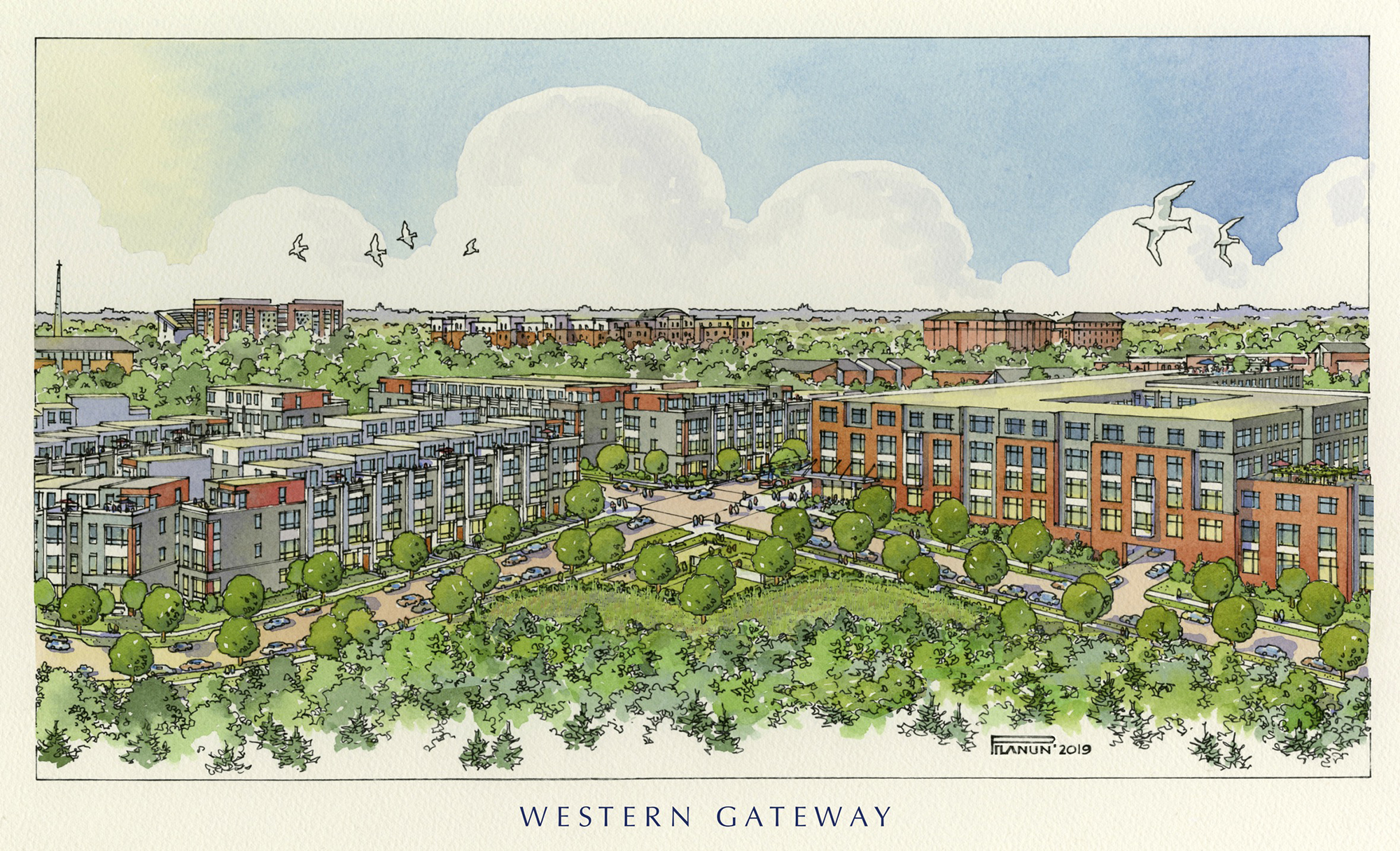

The Gilbane Development Company is moving forward to build affordable graduate student housing on a 16-acre land parcel. The development — called Western Gateway — has sparked fierce backlash among some community members and activists who call the project “fiscally and environmentally irresponsible.”

More than a thousand people have signed a Save Guilford Woods advocacy group petition, addressed to university President Darryll Pines, opposing the project. The petition urges the university to pursue other options for graduate student housing and protect the forested land “as a nature preserve for public use.”

For some graduate students, new affordable housing is a welcome addition. Graduate Hills and Graduate Gardens are the only subsidized options now, and some say they’re not affordable for the value of the properties.

But advocates for preserving Guilford Woods say the environmental toll — which they say could include harming wildlife and causing more flooding in the city — outweighs any benefits.

“I’m all for this development being built,” Lucie said. “But Guilford Woods is absolutely not the place for it.”

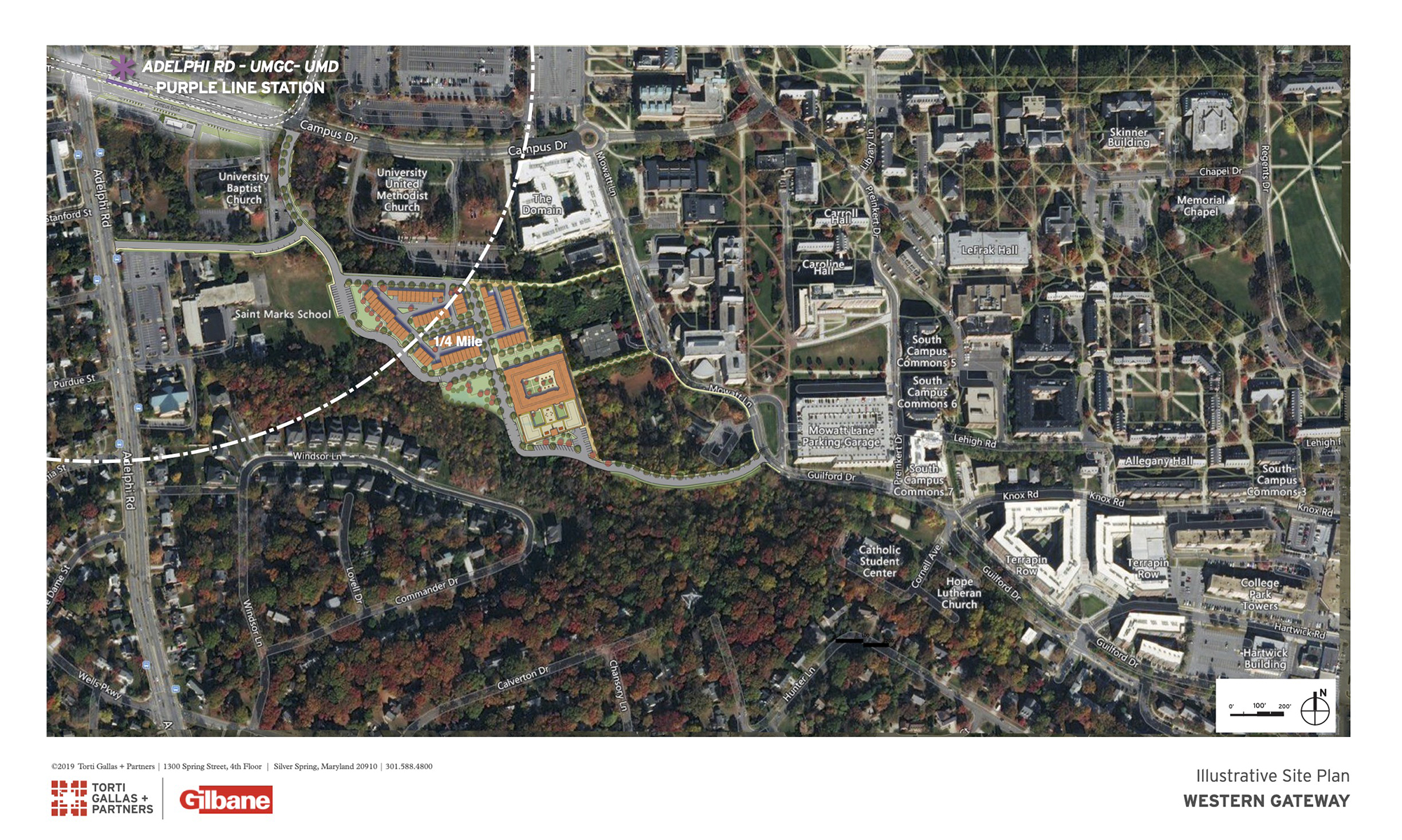

In a 2019 meeting, the University System of Maryland Board of Regents finance committee unanimously approved a 75-year ground lease of 2.26 acres of land to build Western Gateway — a project that is expected to deliver 300 units of subsidized housing for graduate students and 81 townhomes in 2023.

The university also received approval to sell 9.1 acres to Gilbane at the appraised value of $810,000 to “support development of the market-rate townhouses,” according to the meeting notes.

Ed Maginnis, this university’s assistant vice president for real estate, said this public-private partnership will allow this university to increase affordable housing for graduate students without spending tax or tuition dollars.

But those opposed to developing Guilford Woods say this isn’t a smart fiscal decision.

Calvert Hills resident Stuart Adams said the plot of land was priced too low, given how much Gilbane has paid for nearby properties. The price of the land from Guilford Woods, which was set to be sold for under $1 million, is just a fraction of the price of the land for the Tempo project — a 978-bed student housing complex. Gilbane purchased the land that Tempo will sit on for $29,750,000 in January 2019, according to documents from the city of College Park.

“There is some validity to paying more for the Route 1 [property], but paying 170 times more per acre is absolutely bonkers,” Adams said.

[Flooding continues to plague College Park. Here’s why the problem isn’t going away.]

In May, Pines told The Diamondback he met with several Save Guilford Woods advocates, including faculty members with expertise in areas such as infrastructure development and ecosystems, to discuss their concerns.

Although the project proposal has received approval from the City of College Park, the USM Board of Regents and the Prince George’s County Council, Pines said it is still important to hear concerns from the community.

“We hope to then get back in touch with this group down the road to report out some of the factual information that we have regarding the project and alleviate some of the concerns,” he said.

A threat to stormwater management

Ariel Trahan, director of river restoration programs at the Anacostia Watershed Society, said the project would lead to more pollution in the Anacostia River.

Runoff from local roads and parking lots goes into Guilford Run, which empties into the Anacostia, Trahan explained. With less forest cover in Guilford Woods, some local residents and advocates expect less stormwater will be absorbed, increasing the severity of flash floods.

“It would be a real missed opportunity to not preserve this wood and use it as a real showcase for the community, for the state to really show that ‘We are committed to sustainability, and here is a tangible example of our commitment,’” Trahan said.

Meg Oates, who lives in College Park’s Calvert Hills neighborhood, said Guilford Woods provides flood protection for the neighborhood.

But, last September, Calvert Hills — which is prone to flooding — experienced a flash flood. Stormwater covered sidewalks, water rose up lampposts and some residents had to deal with sewage flooding their basements. Oates worries this will increase if some of the forest cover is lost.

Guilford Woods provides other ecosystem services including water filtration and carbon sequestration to the surrounding area, some community members said.

“No matter what Gilbane does to this … development, that development can’t provide all of those things in the same way a forest does,” Oates said.

Some residents and local activists believe the developers and university have overlooked existing stormwater protection and other issues.

But Brad Frome, a University Park resident and consultant for Gilbane’s team working on this project, told The Diamondback in May the stormwater management system that will be built by Gilbane will improve stormwater conditions in the area. The project will include “underground detention facilities” to help manage runoff, according to the project’s website.

“Less water will leave [the area] after this project is built,” Frome said.

Lost habitat

Others have raised concerns about another environmental risk: Animals could lose their natural habitat.

“They’re going to change the environment so much that we’re going to lose [the animals living there],” said Stephen Prince, a geographical sciences professor emeritus at this university who lives near University Park. “They will be gone as soon as the woods are gone.”

Although only about nine of the 40 acres of tree cover near the project will be deforested and Gilbane offered to replant 10 acres of trees on land off-site, “you can’t recreate an ecosystem just by planting a few trees,” Prince said.

[UMD students often turn to off-campus houses for affordability. But challenges persist.]

Aerospace engineering professor Ray Sedwick has lived in University Park for 12 years and has seen the impacts of animals moving to new habitats because of development.

In Sedwick’s community, deer have been displaced after wooded areas were demolished for development.

Now, it’s not unusual for deer to come through his yard and munch on his wife’s azalea bushes or his neighbors’ garden, Sedwick said.

“It’s not that we have any issue with the deer coming through, it’s just, it’s a shame that they’re being displaced from their habitat in the first place,” Sedwick said.

In April, the university’s Student Government Association voted 26-0, with one abstention, on a resolution urging administrators to conduct an environmental analysis of Guilford Woods before any development — which would investigate possible impacts on “the surrounding environment and local ecosystems.”

Still, according to the project’s website, an environmental impact analysis is not required for this development.

To Kurt Willson, the SGA’s former director of sustainability, the university has sustainability policies, including its pillar of smart growth, that it should uphold.

“It looks like a lot of these views or these policies are not going to be upheld in this scenario without that environmental analysis,” said Willson, who graduated in May and studied environmental science and technology and geographical sciences.

The development’s location

Community members have voiced support for the housing development itself, but the environmental concerns have prompted calls to change the development’s location.

Janet Gingold, Prince George’s County Sierra Club executive committee chair, believes land use and planning decisions should take climate impacts into account and this affordable graduate housing should be built on land that isn’t currently home to mature forest.

“Developers often have a tendency to sort of look at a map and see the green spaces as empty places where they can build,” Gingold said. “But these ‘empty places’ are not really empty. They really serve — they provide ecosystem functions.”

But Maginnis said Guilford Woods is the right place for the project because it’s transit-oriented.

In Prince George’s County’s 2035 plan, the county highlighted its goal of reducing vehicle miles traveled. The Guilford Woods location will be less than half a mile away from a future Purple Line station, and Maginnis said the project will contribute to the county’s goal of improving transit access and neighborhood walkability.

In May, College Park Mayor Patrick Wojahn told The Diamondback that this transit-oriented development comes with trade-offs.

While Wojahn is concerned about the tree canopy and other environmental issues voiced by local residents, he said the Western Gateway project is a good opportunity to meet the “well-established and documented need for affordable grad student housing.”

[In a sea of pricey rentals, CHUM is a beacon of housing affordability for UMD students]

Members of Save Guilford Woods and activists suggest the Western Gateway project be built in a separate location that has already seen development.

Adams, who is a structural engineer, said that the space in Lot 1 could be redeveloped to avoid deforestation, explaining that projects such as a parking garage could be added.

These locations could be used for future projects depending on future demand, Maginnis said.

By moving the Western Gateway – which is expected to be completed in August 2023 – to a different location in College Park, the university wouldn’t be able to continue its public-private partnership with Gilbane, Maginnis told The Diamondback.

Gilbane has collaborated with the Graduate Student Government and met with focus groups with graduate students. During a GSG meeting in January, attendees discussed the cost of rent at Western Gateway, which is expected to be as low as under $900 a month.

“Yes, there will be a deforestation, but there is a qualitative difference between cutting down trees so that you can build a 25,000-square-foot single-family house and cutting down trees so that you can house roughly 600 people who are located in the right place,” Maginnis said.

Former staff writer Joel Lev-Tov contributed to this report.