Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

It’s really hard to break through glass ceilings when you don’t have a roof over your head.

Homeless residents in Austin, Texas are coming to this harrowing realization as 57 percent of people in the city voted in favor of Proposition B, which bans camping in several public areas. This proposition would also make soliciting “that is deemed aggressive in manner” illegal within the city, leaving the door open for a possibly dangerous interpretation of the word “aggressive.”

Supporters of this proposition, as well as the city itself, cite public health, safety and property value concerns as to why the move was necessary. But, in this shockingly anti-homeless vote, the city of Austin has decided aesthetics are more important than human dignity. If residents of the city really care about the city’s real estate, public safety and economic development, accessing shelter needs to be easier, not criminalized.

When considering why homelessness has become such a problem in Austin — and the U.S. as a whole — we must examine the current movement of wealth in this country. People are beginning to leave cities, hunting down a more affordable, better quality of life.

Unprecedented growth in certain industries and the rise of pandemic-fueled teleworking has accelerated this trend, with many wealthy workers from New York searching for warmer and more spacious homes in Florida, Nevada and Texas. For a city like Austin, which has been one of the country’s fastest growing cities for some time, this has led to an increase in wealthy people planting new roots in the city.

This might seem like a good thing, and it is — for those in the upper class. As these newcomers plant seeds for new businesses and development, they are covertly weeding out low and middle income residents, who cannot afford these luxury services in their hometown. While rising home values are good news for homeowners, this is terrible news for homeless people and renters, who move further and further away from coveted home ownership. The median list price of homes in Austin was a whopping $500,000 in March. The same city reported its highest rate of homelessness in the past decade in 2020.

Home ownership is not for everybody, and assuming so is not based in reality. But, especially in cities like Austin and here in greater Washington, D.C., — both of which are in the top 10 fastest growing metro areas in the country — investment in a home can be a reliable way to grow family wealth. While paying for a mortgage gets a family a roof over its head in the short term, the equity collected in the home, which can be earned at the time of sale, is a strong way to grow wealth in the long term. With the increase in the median home price, low income buyers will be without this option, sucking them into poverty’s vicious cycle.

The emerging real estate investment crisis will eventually price out middle income earners who can afford down payments on new homes. Homeowners would rather sell to an investor with a cash-only offer as opposed to a 25-year-old with student loans. Unable to become homeowners, low and middle income earners are bound to the rental market, managed by upper class landlords with little knowledge of the difficulties of making ends meet. With another botched federal minimum wage increase coinciding with rising rents, these problems aren’t going away soon. But all politics aside, if someone can’t afford rent and cannot access a mortgage for their own property, they are going to be left homeless.

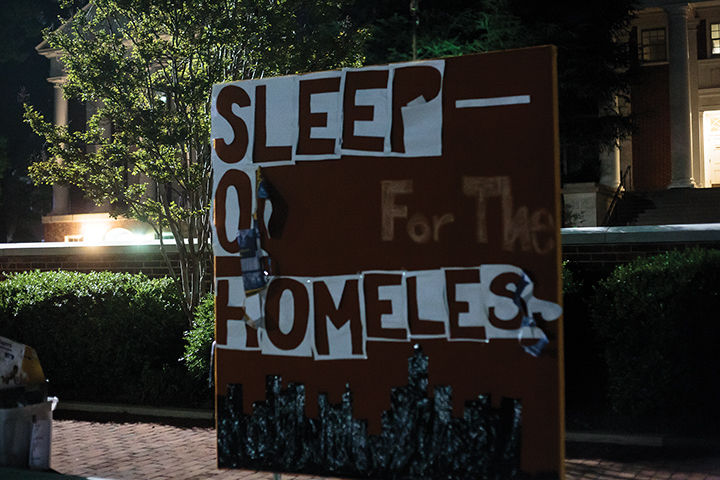

With all of that being said, the crux of the issue becomes clear: We cannot ethically criminalize homeless individuals when they’re simply a product of an unregulated, wealth-and-aesthetic-hungry market. Instead of providing law enforcement more money to further terrorize homeless communities, or prisons more money to house more people, cities should instead invest in programs and solutions that serve homeless folks. For example, initiatives such as providing microgrants to low income families to become homeowners, or establishing college funds for the city’s most vulnerable children, would be a strong place to start these individuals on their journeys of escaping generational poverty. Investing in systems that will stop homelessness from occurring in the first place will help foster vibrant cities full of people ready and excited to contribute toward its continuous development.

But until we stop vilifying homeless people for falling victim to a system they did not create, the cycle has no end in sight. Wealthy families will continue to move to cities such as Miami, Austin and Las Vegas for new opportunities. They will live out the American Dream — while Austin’s poor residents still try to see if it’s even a real thing at all.

Anthony Liberatori is a sophomore environmental science and economics major. He can be reached at alib1204@umd.edu.