I text with the energy of a woman in her 40s — that is, I use a lot of GIFs. They’re silly and convenient, and this year, they’ve filled the void that human faces used to occupy.

According to my iPhone’s screen time breakdown, I spend roughly three hours a day texting. I have no idea if this is normal, and I refuse to disclose my full screen time report for fear of being ostracized. I text way too much, so GIFs save me a few unnecessary moments of typing every day.

But over the last few months, immersed in my GIF keyboard, I’ve noticed something funky about its contents.

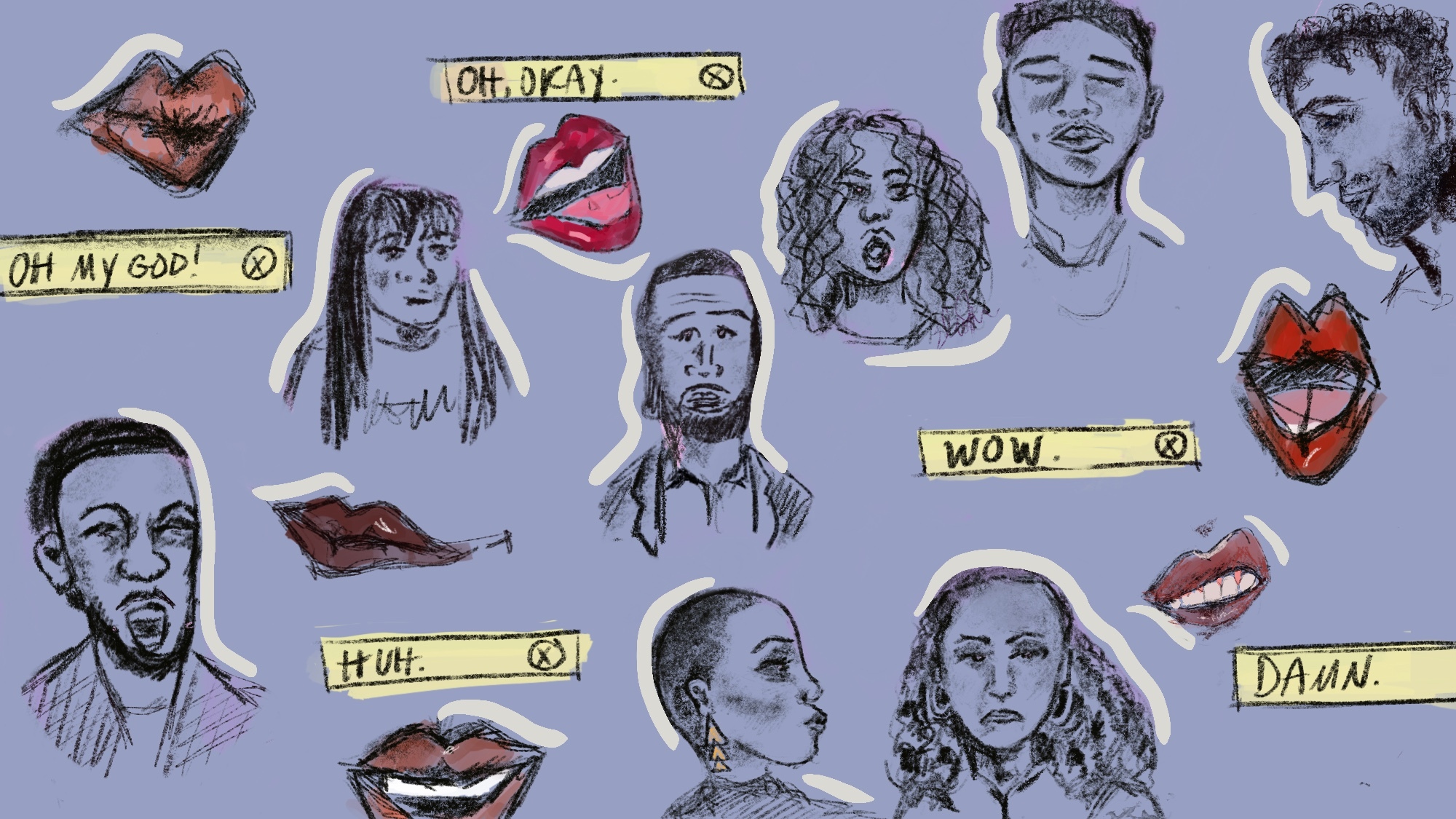

So many of the suggested reaction GIFs are of Black people — specifically Black people expressing themselves in exaggerated ways.

There’s the Michael Jordan crying meme; the Will Smith looking surprised face; the Tyra Banks looking even more surprised face.

When I type “Oh, OK” into my search bar, the first page of the GIF keyboard displays eight Black faces in various stages of disbelief. They’re the perfect expressions for my purposes, but my thumb hovers over the screen.

“Can I do this?” I think. The white faces don’t seem to grasp the concept I’m looking for, which is somewhere between contempt and playful disgust — or, more accurately, shade. But these GIFs mostly interpret “Oh, OK” as “nice, very good” with no irony whatsoever.

Unsure of the correct path, I close the keyboard and type something that feels muted and slightly imprecise.

Or I decide to rely on the old post-racial grab bag of Kermit the Frog GIFs: Kermit thrashing his body in joy or distress in front of a red curtain. Kermit plummeting from the roof of a building. Kermit drinking Lipton tea. Kermit swinging from the paddles of a ceiling fan. Kermit, in his green versatility, soothes my need to visualize my own emotions.

[Normalize eating cake casually]

My racial anxiety is well-documented.

Some refer to the proliferation of Black faces as reaction GIFs as “digital Blackface,” a term cultural critic Lauren Michele Jackson brought into popular lexicon in her viral 2017 Teen Vogue essay, “We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs.”

Jackson argues that Black reaction GIFs function as a kind of contemporary minstrel. Minstrelsy, as she explains, was a performance of Blackness by white entertainers in the 19th to mid-20th centuries who darkened their skin with cork or shoe polish, distorting and exaggerating the Black face into a clownish mask. Jim Crow was a popular minstrel character. He and other characters bore the stereotypical traits ascribed by white people to enslaved African people: laziness, stupidity, lacking in dignity.

Minstrelsy’s roots in American media run deep, Jackson writes — and they contribute to the exaggeration of Black faces and Black emotions on the internet. Consigned to the edges of the emotional binary, the Black face becomes a proxy for emotions that non-Black people can’t process on their own.

“We are your sass, your nonchalance, your fury, your delight, your annoyance, your happy dance, your diva, your shade, your ‘yaas’ moments,” Jackson writes.

But this is old news. Much can change in roughly four years, and much has. And Gify’s most viewed GIFs list of 2020 contains only one shocked Black face; the rest of the images are mostly inoffensive and forgettable. One GIF shows two small genderless figures hugging, with a flashing cursive message above them: “Virtual Hug.” Compare that to Tenor’s 2017 list, when there were four Black faces, including former President Barack Obama.

But that doesn’t mean the imitation has stopped. Rather, it’s simply changed forms.

In August of 2020, WIRED’s Jason Parham explored the way digital Blackface reshaped itself into the TikTok algorithm in his piece “TikTok and the evolution of Digital Blackface.” In that piece, Parham talked to 29 Black TikTok creators who cited experiences of harassment, racism and the platform inexplicably muting their posts. At the same time, Black content was being parroted — often very successfully — by white users. But to what effect?

If you are on TikTok, you might have come across a recently popular lip-syncing trend. Here’s how it goes:

First, there are a few notes of music that almost sound like a Disney overture — bright, maybe a major key. Then, the person in the video balls their hand into a fist or holds it flat up in the air. They punch an imaginary glass wall in synchrony with the music. (Hence, the name of one of the trend’s hashtags, #knockonglass).

A caption materializes, often describing some difficult realization: “Me on my wedding day knowing everyone has to see my side profile”; “When you realize that dressing like a boy who skates won’t attract a boy who skates”; “When you’re legit obsessed with yourself but still insecure,” etc.

They open their mouths and speak. “That’s some bullshit,” they say. Except the voice isn’t theirs.

That voice belongs to the TikTok creator Berleezy. He’s Black.

The people making these videos are of all different races and ethnicities — but there’s something particularly dysphoric about white girls imitating African American Vernacular English.

[Review: Madison Beer’s debut album was held back by indecisive style choices]

I felt the same unease — perhaps more strongly — about the audio clip that circulated for a short period this fall of rapper Cardi B saying “That’s suspicious. That’s weird.” The clip quickly became a shortcut for expressing skepticism.

Why was the trend of lip-syncing to Cardi B’s quote so disturbing to me? Maybe it’s because she has a more recognizable “Blaccent,” although the limits and definitions of the Black voice are hotly debated.

Not all imitation intends to harm, but content can take on a nightmarish quality when it’s divorced from its source, Parham writes. “The way someone or something can so quickly and easily be warped, diluted, recast as something other. The way one’s culture can be stolen and made monstrous, made meaningless,” he writes.

In September, The Diamondback’s diversions editor Manuela López Restrepo wrote “Leave the hot cheeto girls alone,” a piece explaining that a popular TikTok trend that involved dressing in a manner typical of young Latina women — but dialed up a notch, with long eyelashes, longer nails, and big hoops — was yet another instance of ethnic parody.

Black culture seems almost irresistible to young content creators on the internet; leveraging its swagger is a surefire way to be part of the online conversation. The most popular white TikTokers, such as Charli D’Amelio (109.3 million followers and a deal with Hulu, as of December) and Addison Rae (77.5 million followers) rack up views on videos of them dancing and lip-syncing to Black musicians’ music.

If only some TikTokers could integrate the struggle that comes with that swagger.

In white imitation of Black art, there is a kind of flattening — culture context, commiseration and tenderness is excised, leaving only a voice behind. Despite almost a year of widespread racial reckoning, the imitation continues.

We must ask ourselves: Is this the kind of content we want to create? Is this even creating, or is it simply riding on the backs of those who have already done the work for us?