Stefania Amodeo speaks wistfully of a little house folded into the countryside of Genova, Italy. In the summertime, the trees that surround it are filled with cherries.

Amodeo moved to America in 1968, married an American and has American children, but most of her family remains in Italy. Normally, she visits them once, maybe twice a year. But with the coronavirus ravaging the country, she wasn’t able to make the journey this summer. Now, she longs for Italy, for her friends and sister.

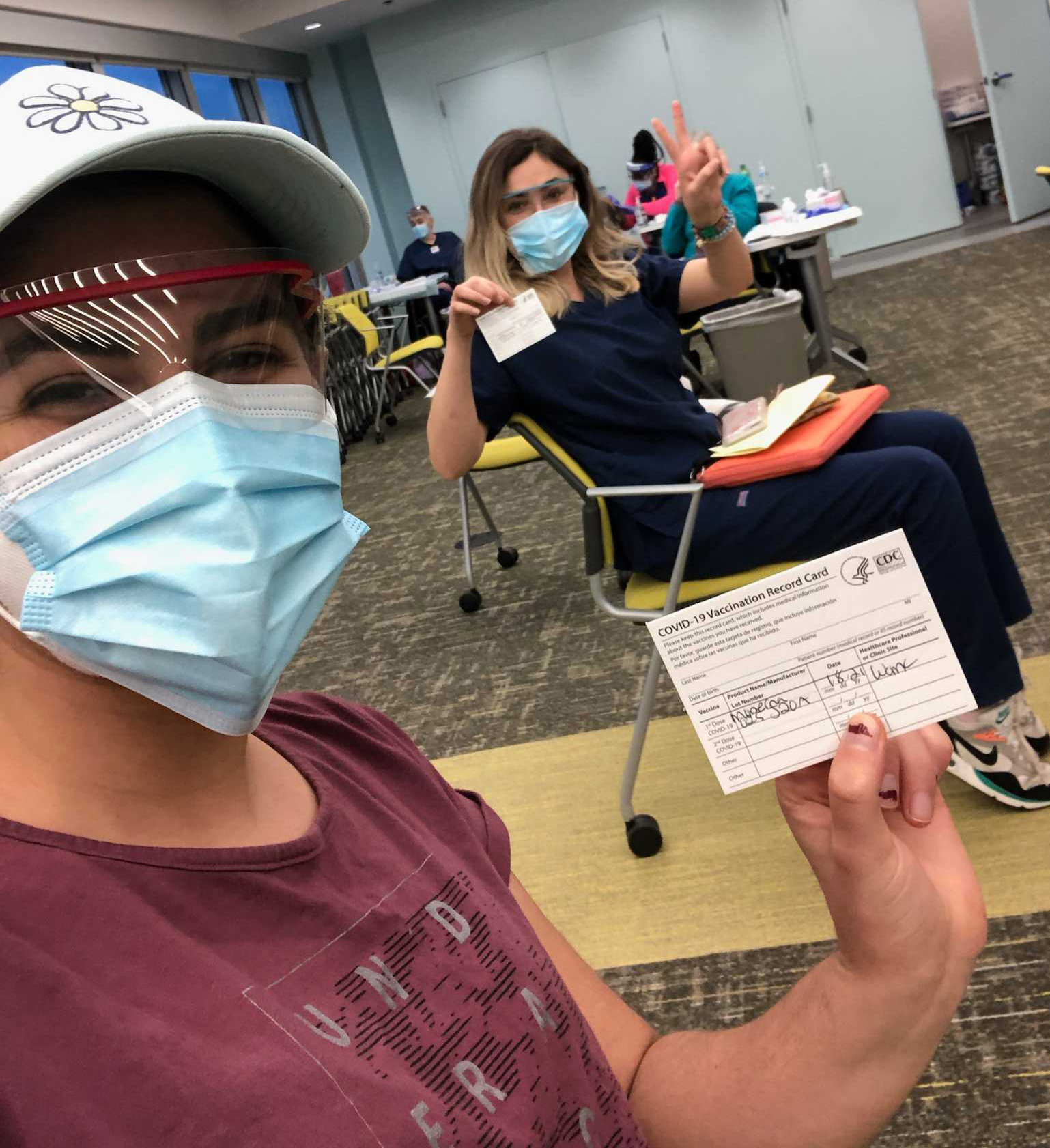

However, their reunion now seems a bit closer. On Jan. 22, Amodeo and her husband received their first doses of the coronavirus vaccine.

And yet, Amodeo — a lecturer in the University of Maryland’s languages, literatures and cultures school — says this does not mean she and her husband are free from the virus. They wonder how long the vaccine will protect them. They are still wearing their masks, she said.

“You hope,” she said. “There is hope. But not certainty.”

As of Tuesday morning, over 39 million Americans, or about 12 percent of the country’s population, had received their first dose of the coronavirus vaccine. Among them are faculty, staff and students at this university who are eligible under Maryland’s immunization plan. Like Amodeo, many are facing conflicting emotions as they confront a split-screen of dueling realities.

Yes, they feel a little lighter when they visit with their god-babies or come home to their grandparents. But more than 485,000 Americans are dead, a disproportionate number of them Black, Indigenous, Latino and other people of color. The vaccine rollout is moving slower than anyone would like, with just 5 percent of people in Prince George’s County inoculated. And new variants of the virus are now onshore, with the potential for even more to develop.

“Maybe it’s Wednesday in the middle of this pandemic. Maybe it’s Hump Day,” said Celina Sargusingh, a clinic coordinator at the University Health Center. “I’m not going to breathe easy yet. But, you know, I do feel more hopeful than I did before.”

[Here’s what you need to know about the COVID-19 vaccine in Prince George’s County]

***

As of Friday, Sargusingh is fully vaccinated. She received her second dose of the vaccine at the same place she got her first: a little tent on the indoor track of the Prince George’s Sports and Learning Complex.

Walking into the center to get her first shot last month felt surreal, she said. The tents clustered around the indoor track and folding chairs stationed six feet apart reminded her of a science fiction movie — more specifically, the ending scenes of the 2011 movie, Contagion.

“I was thinking a lot about that movie like, ‘Oh wow, we’ve gotten to this part of the movie, where it’s time to get our vaccines,” she said, laughing. “That’s nice.”

Now, Sargusingh is comforted by the fact that she is less likely to pass the virus to her children, one of whom has asthma. Her son is also that much closer to returning to school in person, something he’s been itching to do.

But she can guarantee she will not be doing anything differently than before she was vaccinated. She is going to wash her hands just as much, remain socially distanced and keep her mask on, she said.

“I want [the vaccine] to be in my body, doing its job,” she said, “but I’m just going to pretend like I didn’t get it.”

This is precisely what scientists want us to do, said Dr. Stephen Thomas, a public health professor at this university.

Although the race to distribute vaccines has begun, public health experts aren’t telling folks they can relax, Thomas said. Instead, they’re urging people to double up on their masks. Even though Thomas received his first dose of the Pfizer vaccine last month, he is still following that advice.

“If I didn’t know so much, I’d think, ‘Oh, let’s have a party! Come on over for dinner! Bring your grandkids!’” he said. “But what they don’t know is off in the distance, there are clouds.”

As of Thursday evening, 22 cases of the COVID-19 variant first identified in the United Kingdom and seven cases of the variant identified in South Africa had been diagnosed in Maryland. And so long as the virus can get into a human and replicate, Thomas said, it can evolve — possibly to a form that the current vaccines do not work on.

Meanwhile, vaccine distribution efforts are coming up short in Black and Latino communities, even though these communities have been disproportionately devastated by the virus. According to data released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention earlier this month, only 5.4 percent of those who had received the first dose of the vaccine were Black and 11.5 percent were Hispanic or Latino.

As director of the Maryland Center for Health Equity, Thomas is doing his part to push for an equitable vaccine rollout. The network of Black barbershops and beauty salons he initially mobilized in Prince George’s County to promote colorectal health is now distributing information about how to stay safe from the virus and answering the questions people have about the vaccine. Considering the history of medical racism, Thomas emphasized that the distrust some in the Black and Indigenous communities have toward medical institutions has been earned.

But now, he says the country has the chance to right past wrongs.

“We have a window of opportunity of actually solving this problem once and for all,” he said. “Or, we’ll simply go back to the fragmented system that we’ve been living with, with Black and brown people living sicker and dying younger.”

“So, I do not want to go back to normal.”

***

About a day and a half after Jessica Klein had gotten the first dose of the coronavirus vaccine, she drove to an urgent care center, her temperature spiking and her body covered in hives.

The vaccine had given her an allergic reaction. When she consulted with her general practitioner, he advised her not to get the second dose. But that didn’t feel right to Klein. So, she met with an immunologist, who told her that if she were to get another dose, she should be observed for a while afterward to make sure she was alright.

When she got shot number two, Klein, a junior physiology and neurobiology major, brought along an Epi-Pen, just in case. But this time around, the reaction wasn’t as severe. She took an antihistamine that cleared her hives — which weren’t as bad as they were after her first dose — and her muscle aches and mild fever had all cleared by the next day.

It was worth it, she said.

“Despite everything that I went through, I would have done it 1,000 times over again,” she said.

During the pandemic, she watched her friends grieve family members lost to COVID-19. Her uncle also died two weeks after he beat the disease. Her family said goodbye over FaceTime.

She first witnessed the devastation of the virus as a paramedic in her New Jersey hometown during the early stages of the pandemic. After the university sent students away from campus in March, she would often leave in the middle of a lecture that was being recorded to answer a call at the station a minute’s walk from her house. At that time, it seemed like every patient she responded to had COVID-19. The station also didn’t have enough N-95 masks to go around, she said. Any time someone called in with respiratory symptoms, Klein and her fellow EMTs would instead zip themselves up into protective costumes similar to hazmat suits.

One day, she responded to a house in her own community. Now, every time she passes it, she wonders if the woman recovered.

In May, Klein started work as a patient technician in two hospitals. It wasn’t long before she saw someone die from the virus. It was gut-wrenching, she said.

By this time, she says some of her colleagues and friends at the two hospitals have become desensitized to death. But not her. Each time she witnesses somebody die, she thinks of their family. She doesn’t think those feelings will ever go away.

[Dr. Anthony Fauci fields COVID-19 questions at Prince George’s County webinar]

“One night, I had a couple who were the same age as my parents and they were celebrating the same year anniversary as my parents. And they were very, very sick,” she said softly. “It puts it into perspective.”

Sometimes, she’ll hold an iPhone for a patient as they say goodbye to their family. The first time she did this was so hard, she remembered. But now, she tells herself these conversations will bring closure to the family.

Throughout her time at the two hospitals, Klein has also noticed how the pandemic is taking a toll on everybody — from the cafeteria and custodial staff to the nurses. She knows at least four people who left their nursing jobs during the past few months to pick up contract work instead. The burnout had become too much for them to handle.

Despite everything she has seen, however, Klein still wants to attend medical school after college and become a physician. She wants to use her experience as a staff member to push to improve the work environment for others. Doing so will not only support nurses and other health care workers, she said. It will also lead to better health outcomes for patients.

“I’ve always wanted to be a doctor, ever since I was little,” she said. “The goal hasn’t changed, but the why behind it has.”

***

A few nights before Hannah Aalemansour received her first dose of the Moderna vaccine, she had a crazy dream. Although she wouldn’t consider herself to be a particularly wild person, in her dream, she went “haywire” after being immunized, going to restaurants and running all around town. In her dream she even got a single dot tattooed on the injection site.

“Which is totally not something I would do,” said Aalemansour, a senior biology and French major at this university who works at a pediatric doctor’s office in Gaithersburg. “I woke up laughing. But I just carried that energy to the day I got the vaccine.”

One month later, Aalemansour says her habits haven’t changed very much from. Still, she feels more comfortable now when she goes for walks with her grandmother around Washington, D.C. After her grandmother received her second shot earlier this month, Aalemansour took her to visit her sister, who she hadn’t seen in months. It was a sweet moment to witness, she said.

She’s noticed that she isn’t anticipating the end of the pandemic as much as she used to. She wonders if this is because she’ll be graduating soon and doesn’t know what her life will look like in a year. It’s hard to have expectations with so much uncertainty, she says.

However, she knows things will be different even after the pandemic is over. With parents from Iran, a grandmother from France and other ties to Italy, Aalemansour has roots in cultures where kissing, hugging, shaking hands and other physical expressions of affection are huge. But when her aunt leaned in to give her a hug recently, Aalemansour automatically seized up.

“I don’t even know why, because we’ve both been vaccinated,” she said. “In my head, there’s still this huge barrier.”

Although it might take a while, Aalemansour believes the world will eventually return to some form of normalcy. It’s not hard for her to imagine this new reality including a regular dose of the coronavirus vaccine, either.

“When I went to go get my second dose, it was like that sense of novelty was completely gone,” she said. “I just felt like this is a normal thing, and I’m probably gonna do this, like, 100 times in my lifetime.”

Amodeo, the lecturer in the languages, literatures and cultures school, will be getting her second dose of the vaccine sometime next week.

[La Plata Hall residents must restrict activity or return home after uptick in COVID cases]

After 38 years of teaching at the university, this is her last semester. On July 22, she will be turning 80. By this time, she hopes to be in Italy once more.

She will eat cherries straight from the trees and see her sister and friends in person, she said, giggling at the thought of it. She’s looking forward to other things, too.

“Hugging people,” she said. “I am going to hug people.”