Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

Black history is American history, and should therefore be studied, remembered and revered year-round. Let’s start there.

But in a country that’s foundation has been built on the erasure of Black narratives — despite the fact Black Americans built this country — the month of February, Black History Month, is known not only for its great importance and reflection, but also celebration.

But Black History Month was not created for the sole purpose of celebrating Black Americans and their endless contributions to this country. The original purpose of Black History Month was, in large part, a political one aimed at transforming the portrayal of Black Americans as exactly that: Americans. With origins in 1926 as a week to celebrate Black history, founders Carter G. Woodson and Minister Jesse E. Moorland had the primary intention of reminding America of the humanity of its most underappreciated people. Woodson believed that appreciating and understanding a people’s history was an essential step toward equality.

But this history is lost on us today.

In more recent years, as the outcry for racial equity has become part of mainstream conversation, the month has been used by corporations as an occasion to capitalize on the celebration of Black life by aligning their brands with a seemingly more “tolerant” or “progressive” agenda. Sound familiar?

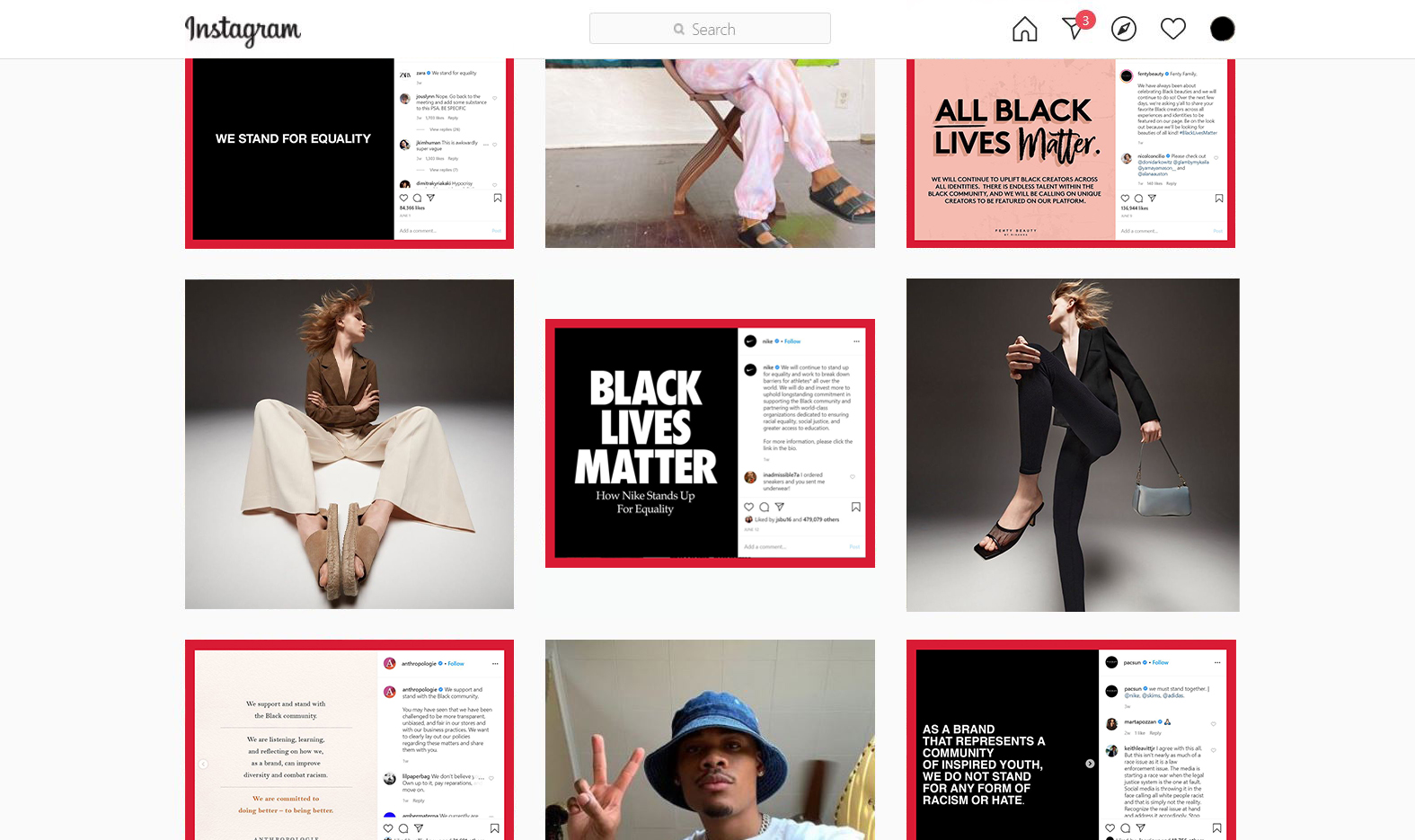

Over the summer, following the police killing of George Floyd, the hashtag #blackouttuesday took flight. Instagram was flooded with black squares — not only from millions of individuals, but also companies who aimed to demonstrate their solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, no matter how performative some gestures may have been.

For example, IBM sent a letter to Congress with policy proposals for racial equality and called for a halt in sales of its facial recognition technology to law enforcement. But, contrary to that promise, IBM continued its ties to law enforcement in ways left unmentioned in the original statement. It proved to be nothing more than a PR stunt.

Other companies followed similar trajectories, choosing to remain silent until called out or until their sales projections appeared to be compromised. One-time donations and cultural sensitivity training weeks were given as long-term solutions, just enough to maintain the support of Black customers. But upon further scrutiny, we can see that many of these “feel-good” campaigns are not even directed toward Black communities at all. These statements are a way to assuage white guilt among these companies’ most prioritized customer base. These campaigns are meant to send the message: “Hey, don’t worry, we’re ethical, keep spending your money here and feel good about it.”

Similarly in preparation for Black History Month 2020, Google released “The Most Searched: A Celebration of Black History Makers.” At a minute and thirty seconds, the video is short, but packs an inspiring punch. But statistics released the same year divulged the bitter secret of performative activism: Only 3.7 percent of Google employees in 2020 identified as Black, a number that has barely increased over 1 percent since 2015. Yikes.

This year, many companies have done no different — despite the protests over summer 2020. On Feb. 1, CBS tweeted a video of a 1955 Rosa Parks interview as a nod toward the occasion, all amid racial discrimination allegations. Facebook has released its yearly Black History Month celebratory visuals while continuing to handle a class action discrimination charge.

Similar to the Black Lives Matter movement, Black History Month presents an opportunity for corporations to profit. These efforts have and will promptly diminish as the month of February comes to an end and companies move on to the next profitable cause: Women’s History Month in March.

However grim, corporations profiting off Black Americans — whether it’s exploiting a movement for personal financial gain, or actively supporting policies harming the community they publicly appear to support — is integral to the American character. But the only way for corporations to truly honor Black History Month year-round is to make structural changes to their businesses that both honor and protect Black life. This means divesting from policing, diversifying their boardrooms and redistributing funds directly to Black communities, to name a few options.

To support Black communities, corporations must go beyond “black squares” and virtue signaling. Without structural change year-round, not just in times of unrest or Black History Month, these gestures amount to nothing at all.

Yahaira Galvez is a first-year poetry M.F.A student. She can be reached at myg@umd.edu.