Going viral: It’s usually something that happens organically, when a joke, poignant statement or goofy video drops at just the right cultural moment to blow up.

In other words, it’s typically not something students are instructed to do for an assignment, especially amid a pandemic. So, when tweets and posts from University of Maryland students began circulating last month, soliciting likes and favorites for that very reason, people wasted no time in expressing their confusion.

“What typa clout chasing assignment is this,” someone wrote.

Another chimed in, “now wtf is the point of this,” adding a laughing-crying emoji after writing, “imma like the tweet to support but why she assign this.”

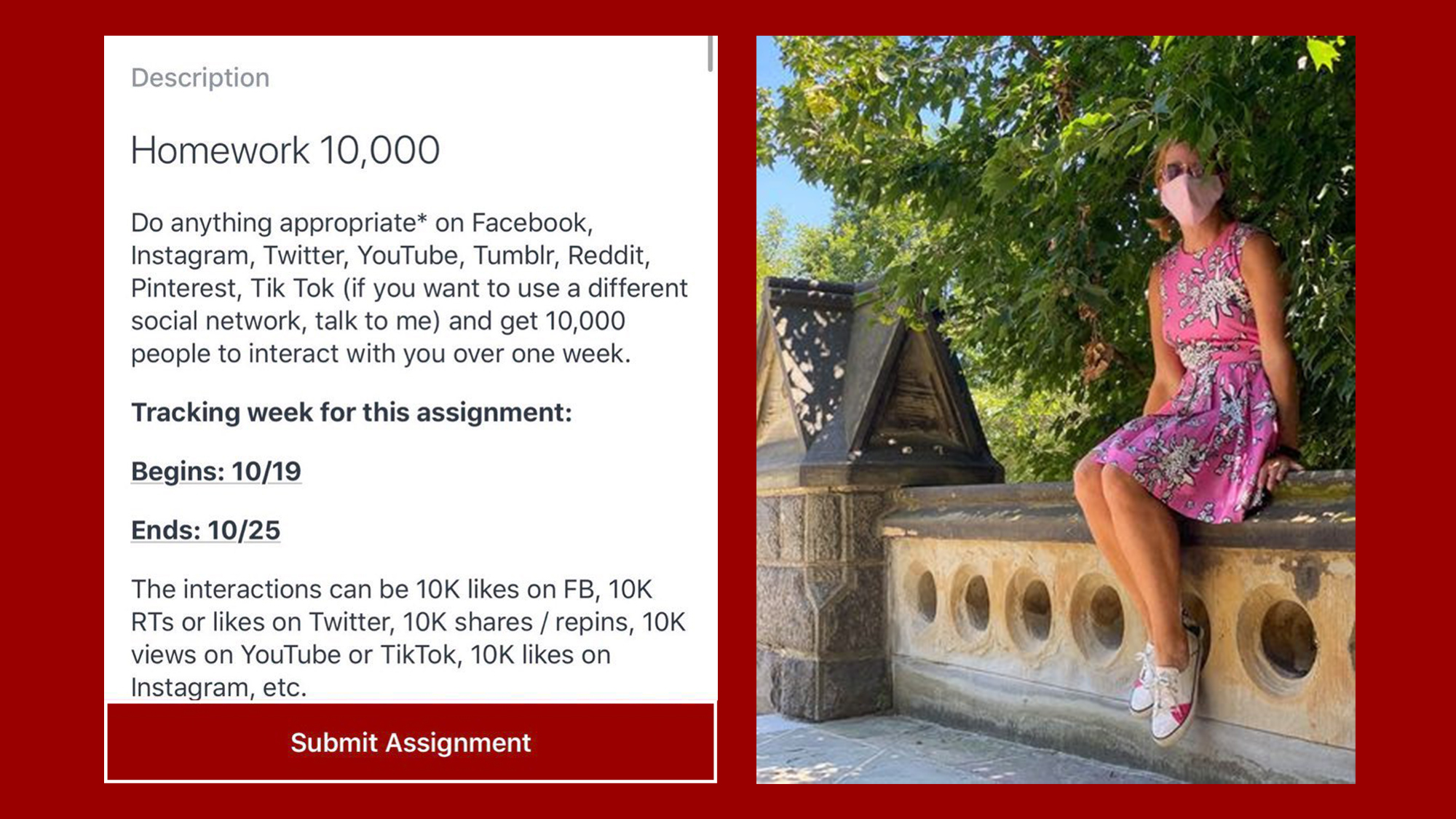

But Jen Golbeck, the information studies professor behind the assignment, stands by it. She said those who react adversely to it typically don’t understand its purpose — or that only a small percentage of her students’ grades are tied to how much engagement their posts receive.

“It tests their understanding of a lot of structure and how things propagate through networks,” she said. “I mean, we use the same kind of models that the CDC uses to track the spread of flu or COVID … so it’s really a very practical application of a lot of interesting theory that they’ve spent six weeks learning up till that point.”

For a decade, Golbeck has taught classes on social networking and the way information and posts spread on various platforms. She currently teaches INST155: Social Networking, a class in the information studies department. By the time she asks her students to attempt to use Reddit, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter or any other social media platform to collect 10,000 or more interactions on a post, they’ve already spent weeks studying how social networks function.

[UMD student group spends day calling Pines’ office to intensify push for union bargaining]

Plus, she said, the grade students receive relies mostly on the strategy they use to make their post go viral rather than on how many likes or retweets they receive. Only four of the assignment’s 14 total points are tied to how much users engaged with the post, and the allotment is based on a logarithmic scale: If they get 10 likes, for instance, they’ll get one point. If they get 100 likes, they’ll get two points.

Golbeck shared observations on the posts that tend to see the most success: Many that perform well, she said, are the ones that involve “begging for likes.” This year, one of those posts hit ten times the required goal.

“That’s never happened before. And it’s basically a post that said in much better Twitter language, ‘Y’all, my prof is crazy, I need to get 10,000 likes,’ and everybody thought it was great,” Golbeck said.

There have been outliers, though. One particularly successful post last year came from someone who had never really used social media, Golbeck said. That student went onto a subreddit of awkward tween photos and posted one of himself at his Bar Mitzvah when he was 13. It had just the right caption, Golbeck said, and it really took off.

Golbeck is coming into this course as an experienced social media magnate: Her Twitter account, “The Golden Ratio,” follows the lives of her multiple golden retriever dogs (and now one labradoodle). She started the account in January 2017, and it has since garnered over 100,000 followers and has an associated YouTube channel, merchandise and Fandom Wiki. Plus, she even got her own Twitter account verified after someone tried to impersonate her.

But junior information sciences major Isaac Santamaria chose a platform other than Twitter to shoot his shot at virality. Having seen other TikToks blow up rather easily, he made a seven-second video with the assignment’s rubric as the background, writing, “These assignments are getting outta hand -_- pls help lol” as the caption. He chose to use Ray J’s “One Wish” as the background track, since it was already trending at the time.

“I posted it, and then I went to work. And then I checked it, and it was [at] 1,000 [interactions],” Santamaria said. “And then a couple of minutes later, [it] was at 2,000 … The assignment was done in like three hours.”

He thinks one of the big reasons behind his success was the support of his friends and family: His brother posted a link to the video on his Golden State Warriors fan page, which has thousands of followers.

Golbeck affirmed Santamaria’s suspicions. Unless you’re an influencer, she said going viral is all about getting the post in front of the right people, who will then share it with others.

“[You] have to think about, how do you get a lot of people to share it so it reaches a much bigger audience?” she said.

[Richard Rothstein discusses housing segregation at public policy school webinar]

Not all of Golbeck’s students manage to go viral: The image freshman Segun Awe tweeted, for instance, peaked at around 800 likes, only to level off for a few hours. The next day, though, he said engagement on the post surged again. Currently, the tweet — an image of Baltimore Ravens quarterback Lamar Jackson sitting on the sidelines with sunglasses on, captioned with a description of the assignment and a request for likes — sits at nearly 4,000 likes.

Though he said he thought the assignment was insane when it was first announced, once he read its rubric and realized he could get a good grade just for trying, he felt better.

“While I was doing that assignment, it was pretty fun to me,” he said. “And I enjoyed it.”

For people trying to become influential on a big stage or even just reach others and create content for a smaller passion space, Golbeck said being skilled just isn’t enough sometimes.

In these cases, she said, understanding how posts can pick up steam on social networking sites can be useful — that way, you’re not sending out good stuff and having it go unseen.

“Even if it’s a really small group, understanding the structure of these things and how they spread … that becomes important,” she said. “You have to understand the structure of these things and how it works if you want to be successful.”