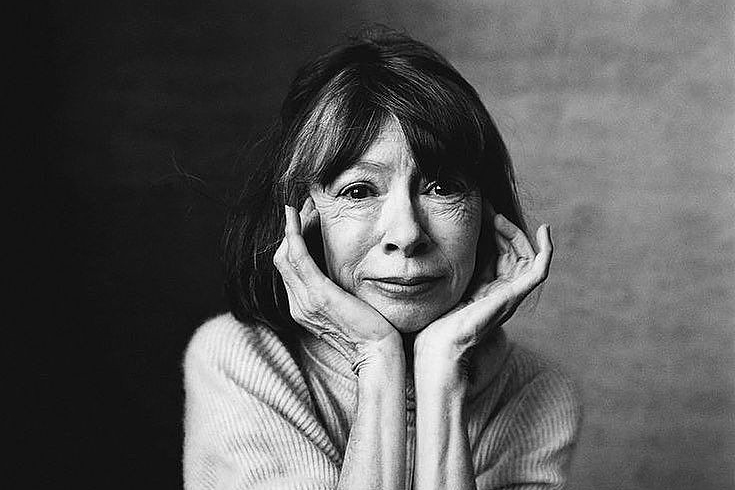

In her 1967 short essay “On Going Home,” Joan Didion held a mirror to that “nameless anxiety” you feel when interacting with where — and who — you come from. And now, as college students have suddenly and indefinitely returned to their childhood homes, today’s generation is faced with the same question Didion posed over 50 years ago: Can you ever go home again?

She offers no solution or remedy — in the most Didion way possible — but just puts words to something you didn’t know existed outside yourself. And as Generation Z steps up to make the next 20 years much different than the last, this question is one we’ll be asking again.

I first read Slouching Towards Bethlehem, a collection of Didion’s essays, during freshman year for an English class, but only the required chapters. I didn’t make it to “On Going Home,” featured in the collection, until last semester — coincidentally the same week the university announced its move to online classes.

I read as Didion carefully and precisely reflected the tension I felt walking into my childhood bedroom; no matter how welcoming, loving and positive my parents were, my bedroom felt so unapproachable that I ended up spending quarantine in the basement instead.

In the span of 1,187 words, Didion takes us through her “home,” where she grew up and occasionally visits her family, versus her home now, where she lives with her daughter and husband. A few paragraphs in, she asserts that “those of us who are now in our thirties were born into the last generation to carry the burden of ‘home,’ to find in family life the source of all tension and drama.”

Didion then confronts the physical house, saying, “Paralyzed by the neurotic lassitude engendered by meeting one’s past at every turn, around every corner, inside every cupboard, I go aimlessly from room to room. I decide to meet it head-on and clear out a drawer, and I spread the contents on the bed.” She goes through her belongings, finding a rejection letter from The Nation, old teacups and a photograph of her grandfather skiing.

[Halle Berry’s apology isn’t enough]

She captures disconnected conversation with extended family — ones who don’t know she’s moved apartments or states. There’s casual mention of the death of a distant cousin, then a birthday party. Didion ends by wishing her daughter a home like the one she had growing up, with cousins and uncombed hair. But no promise can be made in good faith except one to tell her a funny story.

It’s not a happy essay, especially revisiting it after these past few months.

Like Didion, I felt the need to tackle that emotion head-on by undoing my bedroom, by rereading old diaries. There was a rediscovery of old biology tests and books I had forgotten I was obsessed with, such as The Outsiders and Eleanor and Park. And although that satisfied to some degree my need to reconcile with my home, it did not offer me answers.

And Didion captures that feeling perfectly when she wrote, “There is no final solution for letters of rejection from The Nation and teacups hand-painted in 1900. Nor is there any answer to snapshots of one’s grandfather as a young man on skis, surveying around Donner Pass in the year 1910.”

There is a certain level of loss you feel when returning to your childhood bedroom, like realizing you’ve been kicked out of a club you used to be president of. It’s easy to chalk this feeling up to time passing, if you analyze it when you’re finally visiting home at age 30. But for this year’s premature migration home — and all the subsequent events — there seems to be other factors besides 12 years of passed time.

Didion sees it as a generational occurrence: something born out of a romanticized “dark journey,” fueled with questions of drugs, politics, sexuality and independence. Perhaps experiences such as those had made the abyss between who you were and who you are too great to bridge.

[How ‘Hamilton’ highlights lessons to be learned during times of revolution]

In the past few months, Gen Z has seen its own “dark journey,” fueled by what’s been called the “two pandemics” — COVID-19 and systemic racism. Images of police brutality have been projected into living rooms everywhere, forcing a confrontation delayed by years of oftentimes willful ignorance. When those pandemics have claimed all their victims, we will feel their loss, too. I won’t list all the ways we’ve been scarred — and there will be varying degrees of that for everyone — but they will be felt long after all seems healed.

Like Didion’s generation, Gen Z has a lot to face when we inevitably go home again in 20, 30, 40 years. How can we look at a room made up of relics left behind? The stuffed animal you decided not to take to your first year of college, the book you left half-read on the side table. There’s hesitation to move anything in case the true owner and occupier decides to come back.

Not only will the unresolved questions of childhood felt in March still be hanging in the air, but the feelings of rage and confusion, loss and helplessness — yet also empowerment — from a tumultuous year will come flooding back. And we will not be who we were when we last walked out the door.

Our childhood homes are no longer just made up of the hand-painted mugs, band posters and Nintendo devices that seek to remind us we can’t move forward without leaving something behind. Those questions now include any baggage we manage to drop off and attempt to leave in 2020.

When Didion describes home as a “burden,” it feels like a certain betrayal. How can you be thankful for and burdened by the same material? All I know is I couldn’t even finish this article, which I started writing at my home in Connecticut back in April, until after nearly two months of living in New York for an internship. The weight of a home doesn’t give room for active reflection — it’s not until you leave that you can look back.

But as limiting as a home is, you still search for parts of it anywhere you go.

There are no answers in the home, only a reminder of the questions. That was true for Joan Didion 53 years ago when she penned “On Going Home,” and it is true now. And in another 20 years when we are forced to confront the shelves, photos and all their contents, it will remain true.