Two weeks ago, the University of Maryland shut off the air conditioning in multiple dorms across campus as part of its efforts to control moisture in the buildings. But, even as temperatures hit the 90s in College Park, work hasn’t stopped in these buildings — and some employees are falling ill.

Since June 26, when the university turned off the air conditioning in these buildings, the union that represents workers on campus says it has heard from several employees who have sought medical attention after working without air conditioning. Each day, the number of workers getting sick grows, said Marc Seiden, an organizer for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Council 3.

“It’s totally unacceptable,” he said.

In the fall of 2018, students found mold growing in at least ten dorms and on-campus apartment buildings. Since then, the university has taken steps to control moisture in dorms, including installing dehumidifiers, replacing roofs and upgrading HVAC systems.

But the union says its latest measure — turning off air conditioning in certain dorms and allowing fresh air to circulate throughout the buildings — puts the health of workers at risk.

Since last week, Nyeisha Clark, a lead housekeeper at the university, has worked without air conditioning in Allegany Hall. Even though she and her coworkers have been provided with fans, Clark said they don’t do much to cool down a hot building. They just blow hot air around, she said.

[UMD union still concerned on-campus workers aren’t getting proper supplies, guidance]

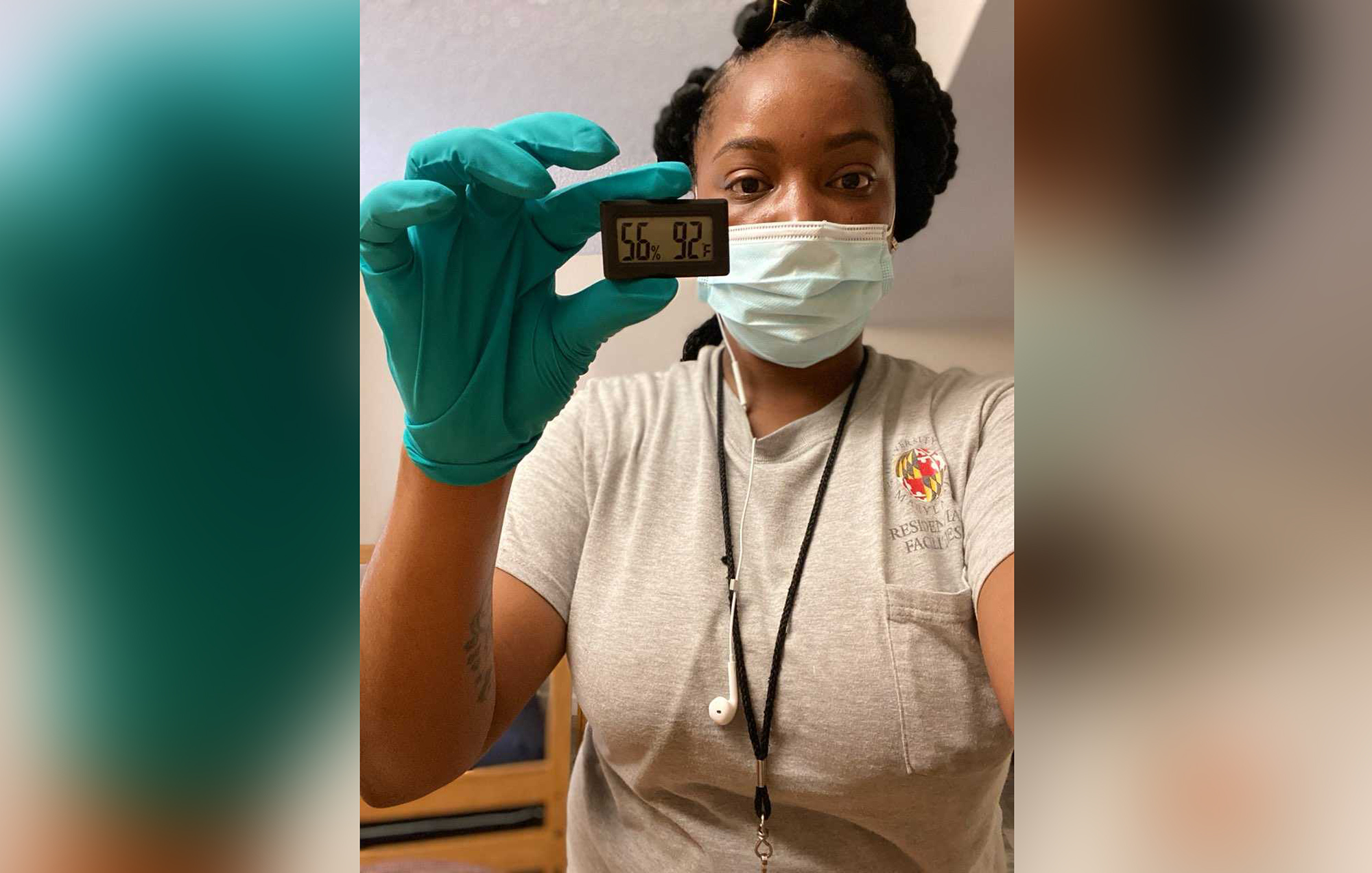

On July 1, Clark was feeling so sick that she left around 8:30 a.m. to see a doctor. There, she was told that her oxygen levels were low. She stayed home the next day to recover, but as of Tuesday, she was back at work in Allegany. Using a thermometer provided by the union, she recorded the temperature as 92 degrees at 9:30 a.m. And it only got hotter throughout the day, she said.

“It’s bad outside with the mask, so imagine working in a hot building for eight hours,” she said.

Along with setting up fans, university spokesperson Katie Lawson wrote in an email, the school has implemented work rotations that minimize cleaning in buildings without air conditioning.

Additionally, she wrote, housekeepers working in buildings without air conditioning are being encouraged to work at a slower pace and take more frequent breaks. They’ve also been provided with access to cold water and an air-conditioned space where they can take breaks, Lawson wrote.

“We are looking – and will continue to look – for ways to have staff work in buildings that do have air conditioning, based on daily weather forecasts,” she wrote.

However, Todd Holden, AFSCME Local 1072’s interim president, questioned whether the university would have shut down the air conditioning systems had the campus been operating as it usually does during the summer, with people attending conferences, kids participating in sports camps and students taking summer classes.

“It matters that people are in those buildings working,” he said. “And whether or not they are contributing to the bottom line at the university or not, their health and safety is just as important as anyone else who would be occupying those buildings in the summertime.”

What the university is doing, Holden said, is trading one health and safety concern for another. During the 2018 fall semester, dozens of housekeepers reported illnesses to the union after cleaning mold-infested dorms, which they said they weren’t provided proper cleaning supplies or guidance to do.

On Monday, Antoine Peterson, another housekeeper at the university, left work early after cleaning in Centreville Hall without air conditioning. Peterson has chronic asthma and began experiencing chest pains after working in a hot building all day. Previously, he worked in Bel Air Hall, another building with shut-off air conditioning.

Now, Peterson is using his personal leave to take time off until Monday. When he returns to campus, he hopes it will be in a building with air conditioning.

“I don’t know if it’s against the law, but I know it’s unhealthy to be working like that,” he said.

[UMD faculty and students say they’ve been getting sick from mold in Woods Hall for years]

While the Occupational Safety and Health Administration does not have specific regulations regarding temperatures and humidity in an office setting, it recommends that temperatures be set between 68 and 76 degrees Fahrenheit.

Additionally, Holden said, the union’s contract requires the university to provide a robust health and safety program. That means the university has an obligation to ensure workers are not being placed in dangerous situations when they come to work, he said.

On Wednesday, Holden says, the union will be speaking with university officials about the school’s decision to shut off air conditioning in buildings where its members are working. At the very minimum, he says, the union is calling for the university to make sure employees have air conditioning where they work.

“AFSCME encourages the university to engage with us on these issues because we represent the employees. We have lines of communication open to them in ways that the university does not,” Holden said. “We’re the ones who are most positioned to come to agreements with them that are going to protect everyone’s safety on campus going forward.”

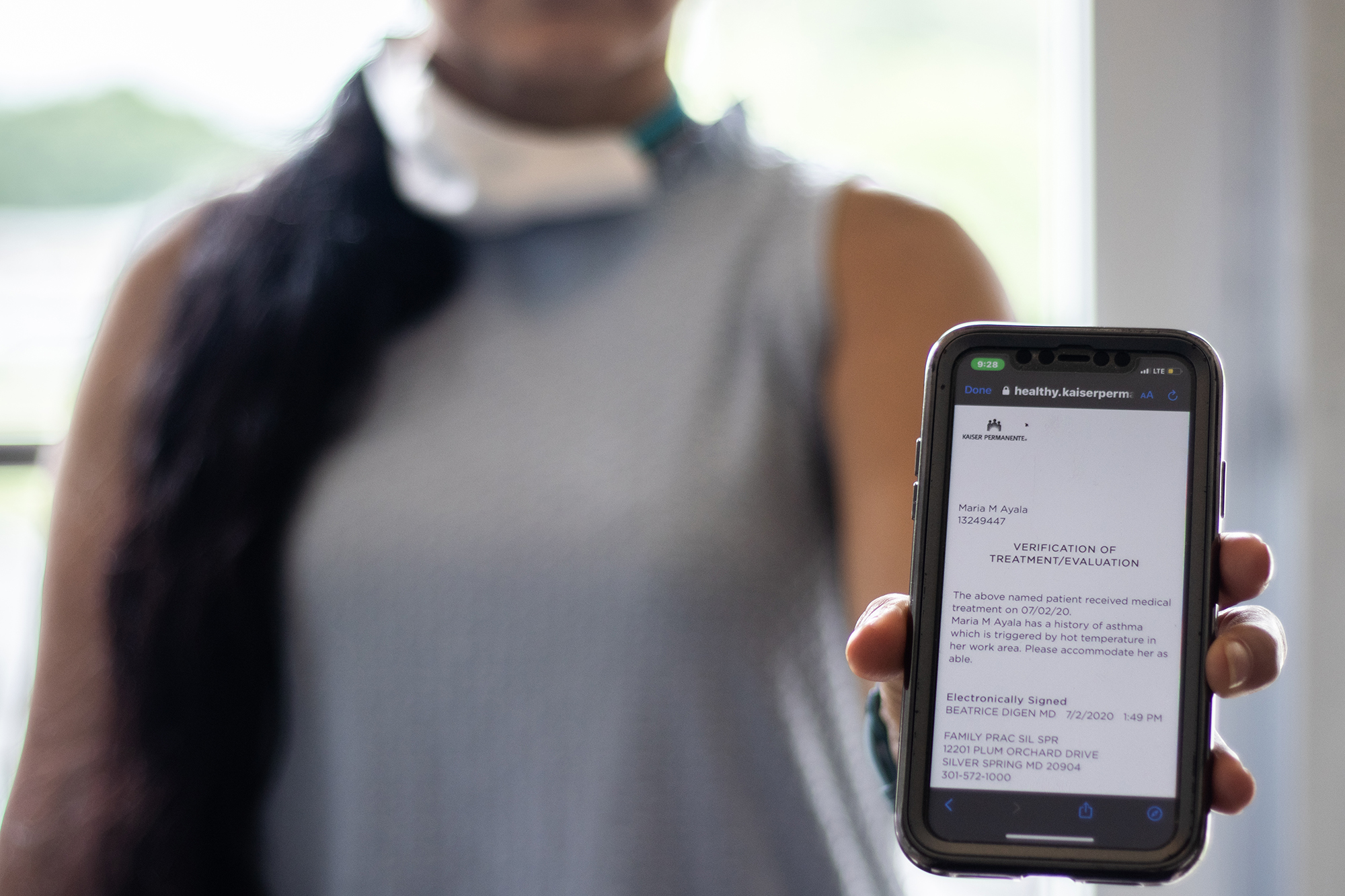

Meanwhile, Maria Ayala, another housekeeper at the university, has been taking unpaid time off since June 24 after falling ill from working in an apartment in Old Leonardtown with no air conditioning. At first, she thought her symptoms signaled COVID-19 — her chest was tight, her head ached and her stomach was upset.

But she tested negative for the virus. Instead, her doctor told her that working without air conditioning — on a day when temperatures hit a high of 89 degrees — had aggravated her asthma. The mask she and all employees on campus are now required to wear only made it harder for her to breathe, Ayala said.

The university spokesperson wrote in her email that a broken air conditioning unit in Old Leonardtown has since been repaired. However, Ayala has stayed home from work — forgoing the $500 check she gets every other week — because she knows her asthma will act up again if she returns to cleaning buildings that don’t have air conditioning. She’s considering returning to work on Monday, now that her supervisor has told her she can work in buildings with air conditioning.

“We deserve better. For the things that we do, we deserve better,” she said.