When Saul Walker saw the footage of Rayshard Brooks, a Black Atlanta man, being fatally shot by the police on June 12, there was only one thing he could say.

“Here we go again,” Walker said at a town hall held Tuesday by the University of Maryland’s Nyumburu Cultural Center and the Black Faculty and Staff Association. “I mean, here we go again.”

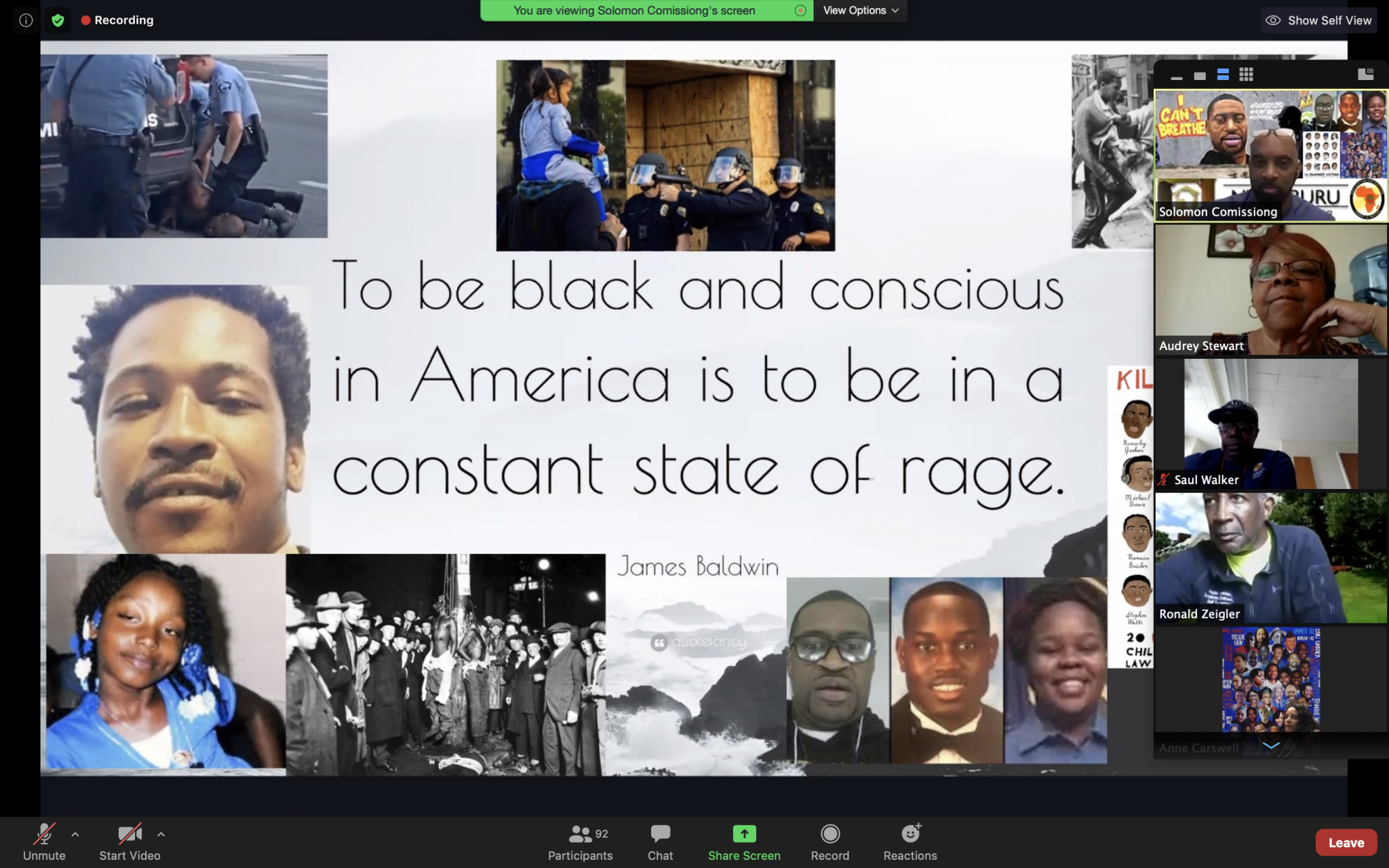

At the town hall, designed to foster a “cathartic and therapeutic medium,” students, faculty and staff were given the chance to talk about yet another case of police brutality. But it was also a place for them to provide testimonials of racist incidents on campus, Solomon Comissiong said.

“We have to start with our campus community,” Comissiong, BFSA president, said.

He’s heard stories of Black students being called racial slurs on their way home from the bars. He’s heard the story of a Black student who has been pulled over by police officers more than 20 times over their four years as a student. He’s heard the story of a professor in the African American Studies department who was arrested because of suspicions he stole the brand new SUV he was driving — the brand new SUV that belonged to him.

These racist incidents, Comissiong said, create a culture that allows “heinous” things to happen, such as the death of 2nd Lt. Richard Collins.

“This university needs to do more than just lip service,” Comissiong said. “We need policies in place that ensure … it is not something that’s accepted on this campus.”

[UMD professors discuss racism on campus, consider policing reform at town hall]

In a statement, a university spokesperson said the town hall is a critical way for community members to speak about their experiences.

“The conversations shed light on topics that the university is actively engaging in, including providing necessary resources that serve to aid and support our Black students, faculty and staff, and working to create an anti-racist campus,” the statement read.

Several in the town hall also criticized diversity reviews the university has released, saying they’re part of the university’s “pattern of silencing” racial issues on campus to avoid negative effects on enrollment.

An external review of diversity and inclusion at the university was highly criticized after it was released in late November 2018. At the time, Comissiong said he was shocked to see next to no individual quotes, perspectives or anecdotes from the campus leaders interviewed.

Black and Latinx students “bled their hearts out” to those working on the report, Comissiong said. They told the stories of their experiences on campus as students of colors, only to receive an erring response from the university, Comissiong said.

“The university said … ‘We don’t want your narratives out there,’” Comissiong said, his voice rising with anger. “We don’t want the university and the broader world to know your pain and what you have gone through … we don’t want that to get out there. We don’t want it to mess up our dollars and our investors and students … we don’t want parents to hold back their money.”

The death of Jordan McNair, a Maryland football player, was cited as an example of this pattern.

McNair suffered heatstroke during a team workout in May 2018. When treated properly, heatstroke has a 100 percent survival rate — but medical personnel failed to recognize the severity of McNair’s condition, and paramedics weren’t requested until he had a seizure. He died two weeks later.

In August 2018, the university publicly claimed “legal and moral” responsibility for his death — two months after the fact. The situation prompted two external investigations: one into McNair’s death and one into the football program’s culture.

“He died, lost his life tragically, died, in late spring,” Comissiong said. “And when did the university acknowledge that? It wasn’t until August, and it wasn’t on their own. It was because ESPN blew the story up.”

For Jerry Lewis, who has been the executive director of academic achievement programs for almost 50 years, today’s climate is the most promising in terms of change, he said.

“The opportunity is really ripe to have improved campus climate, hiring patterns on the campus and treatment of employees on campus,” Lewis said. “I really want us to sort of dissect what we’re feeling into an action plan on some very specific things that we can deal with on the campus.”

As a start, they need to get the records of student complaints against police, he said.

“It should be public information. If police have been accused of brutalizing people and making arrests, we need to talk about it. But they have to make reports,” he said. “There’s no reason why we can’t focus on trying to ascertain those kinds of reports, put them in some kind of order and some type of position proposal, and move forward to eradicate some of the changes that we’re talking about our police department on the campus needs to deal with.”

[At town hall, UMD black community members vent anger after George Floyd’s death]

Shortly after Lewis spoke, an attendee invited University Police Chief David Mitchell, who had been in the town hall as some shared their negative experiences with officers, to speak.

Mitchell started off by denouncing the situation that resulted in the death of George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black Minneapolis man who was killed in police custody. The police officers involved should have been arrested immediately, he said.

He then pledged to continue holding his officers to high standards, referencing their training academy and explaining that the current training class will be watching the recording of the town hall to learn how the community feels.

“I feel the anger, I am angry as well,” he said. “I want to continue to make a difference here on our campus.”

Mitchell said he will not stand for racial policing, but people need to file complaints so he can take appropriate action.

“But it’s well beyond me and the university now,” he said. “This is nationwide.”

Additionally, he said, University Police are in the process of reviewing their procedures. They have committed to not using pepper spray on lawfully abiding protesters. They produce annual reports on the use of force.

Toward the end of the town hall, an attendee raised a question — if the United States had a civilian organization that killed over 1,000 largely unarmed people every single year, what would the U.S. government call that organization?

Another attendee answered: “Terrorism.”