By Thomas Hughes

For The Diamondback

Time comes for us all. It is a truth country music seems uniquely equipped to understand, a genre that idolizes reverent platitudes and starry-eyed references woven between lines, the modern descendant of folk tunes passed across countries and states until the very dirt they crossed became sacred.

Even so, it’s difficult to comprehend the wave of grief since John Prine, the oddball turned paternal folk figure, passed away last week due to complications from the coronavirus.

The comeback is hard-wired into American culture and occupies near cult-like status in country music. Luminaries have descended from their outlaw pedestals to return to their studios, their voices, coarsened by years of hard living, lending their time for one more critically-acclaimed turn, from Johnny Cash’s 2002 cover album American IV to Tanya Tucker’s While I’m Livin’ in 2019.

But the “comeback” label does not lend itself well to John Prine, an artist who averaged an album about every 2 ½ years since Nixon’s first term until 2018. Was his comeback in 1996, following his diagnosis of neck cancer and subsequent treatment that left his voice — and its charming Ohio River valley twang — with a gravelly tone that would make Cash blush? Or was it in 2013, when he underwent surgery for lung cancer and returned to touring in just six months?

It’s possible our notions of narrative simply weren’t designed for the singing mailman. In a time when urgency has invaded our lives, when every election is hailed as the most important ever, when outrages and celebrity soar past us, fizzling like comets once we dare to look away, there’s something striking about a man whose songs seem better suited to a campfire than a stadium.

[Read more: Review: Ashley McBryde’s fourth album is everything great about country]

Frenetic energy has overtaken music, with pulsating beats that feel naive next to the easy strumming of Prine. The protege of outlaw country icon Kris Kristofferson and child of Chicago’s Vietnam-era folk revival vacillated from the haunting songs that won him praise from Bob Dylan to the goofy songs that seem more suited to the Muppets than the Highwaymen. Belying it all was Prine’s masterful marriage of the absurd and brutal reality.

The former mailman’s literary range far eclipsed his vocal stylings. There’s “Sam Stone,” possibly the saddest song ever, where Prine ruminates, “There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm where all the money goes … Jesus Christ died for nothing, I suppose.” Then, there’s “In Spite of Ourselves,” where Prine ruefully sings, “She thinks all my jokes are corny, convict movies make her horny,” only for frequent collaborator Iris Dement to retort, “He ain’t got laid in a month of Sundays, caught him once and he was sniffin’ my undies.”

Of recent, a lone guitar has become a sort of well-laid trap, its vulnerability luring its audience in for songs turned manifestos. In Prine’s hands, however, country’s bygone days of near-prudish euphemism over gentle chord progressions seem less distant. There’s 1999’s In Spite of Ourselves, where every song (with the exception of the album’s closing track) is a duet with a celebrated woman in country music, including Patty Loveless, Emmylou Harris and Trisha Yearwood.

The album’s remarkability is only eclipsed by its successor years later in 2016’s For Better, Or Worse, featuring the likes of Kacey Musgraves, Miranda Lambert and Alison Krauss. It’s hard to discern whether the album is a better watermark of the respect Prine has earned, drawing such a vast collection of musical forces, or the humility to dedicate such energy to collaborative projects.

Despite its relaxed demeanor, his music never lacked exigence. His urgency is not absent, but rather hidden. It’s there in “Some Humans Ain’t Human,” his excoriation of genteel reactionaries. It washes through his gravelly tones as he recounts his irritation with the Silent Majority’s seemingly unquestionable patriotism in the self-explanatory “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore.”

Prine seems to have gladly embraced his role as grandfather to a new generation of eccentric innovators. It’s clear as he sits, smiling, opposite Kacey Musgraves before her critical darling Golden Hour, convincing her to perform a track she never released, “Burn One with John Prine.”

It’s clear as he stands under bright lights with confessed fan Stephen Colbert, crooning his old standard, “That’s the Way That the World Goes ‘Round,’” together. And it’s clear as he warbles along to “In Spite of Ourselves” on stage alongside Amanda Shires. Just behind them is her husband, Jason Isbell, penman in his own right, whose Iraq War protest song, “Dress Blues,” has Prine’s fingerprints all over it, plucking along on the guitar.

[Read more: Review: ‘The New Abnormal’ provides melancholic nostalgia]

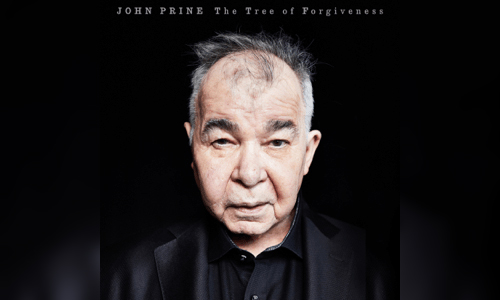

Prine’s contradictions are most evident in his 2018 release, Tree of Forgiveness. He bounces from one paternal instinct to another, from the ageless joy of “I Have Met My Love Today” to the spryly nonsensical “Egg & Daughter Nite, Lincoln Nebraska, 1967 (Crazy Bone)” to the wistfulness of “Summer’s End.” It was this album — where he perhaps lays most bare his own mortality — I turned to for comfort as I heard news of his dire condition.

Prine’s greatest attributes are all there, beginning with the cover art: a simple photo of him against a black background in all his wizened glory. The trademark mullet and mustache are replaced by silver tufts of hair and a mouth permanently askew. Time has creased his face but his eyes are dark, and sharp as ever. His thoughtful eye on America’s disappointing reactionary tendencies has not faded with age, as he lets us know with “Caravan of Fools.” Nor has his radically forgiving humility, as he ruminates on his own shortcomings.

It feels jarring to listen to such contented music now. Tears welled in my eyes during “Lonesome Friends of Science,” as he remarked upon the hard luck of the dwarf planet Pluto. They subsided before “When I Get to Heaven,” the album’s final track. As he outlines his plan for good-natured chicanery upon his death, the delight of a life well lived is in his croaking joy. “I wanna see all my mama’s sisters,” he sings. “‘Cause that’s where all the love starts.”

Suddenly, I found tears streaming down my face as his unbridled love rang with a glory hard to imagine in a voice so unapologetically scarred. Perhaps the one best prepared to consider the eventuality of a world without John Prine was Prine himself. And for that, we owe him a debt.

The day after he passed was a glorious one. With his words echoing through my head, I set off on a run. A few miles in, I stopped at a deserted red light. A mail truck pulled past me and Prine’s song “Hello in There” — most relevant in a time of quarantine and the prime choice of tributes — echoed through my head. I smiled and waved as the truck trundled on past. The mailman within turned and his face broke into a grin as he waved right back.

We cut a strange pair — me in my electric blue running shorts, panting and sweaty, and him, thin but ruddy-faced, hair like steel wool poking out from the mask pulled down around his neck. The sun shone through the moment, tragedy and beauty crystalline and surreal.