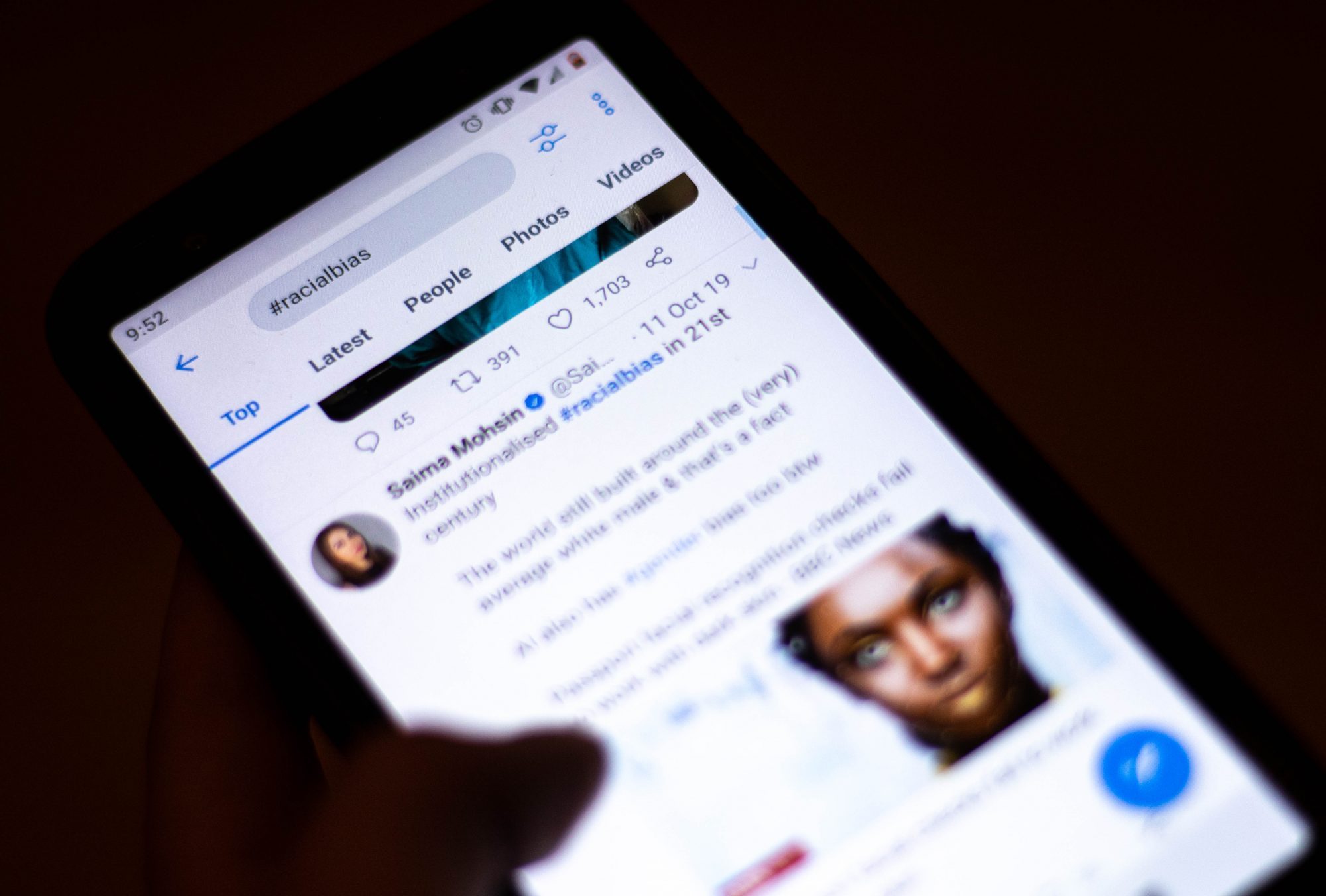

For the last five years, a University of Maryland research team has been exploring the connection between racial bias and community health — by using Twitter.

From 2015 to 2018, the team tracked tweets that mention race and saw how they lined up with the cardiovascular disease cases in an area. They found that negative sentiment towards racial and ethnic minorities is associated with overall poor community health.

Last month, Quynh Nguyen, an epidemiology and biostatistics professor, and her doctoral student, Dina Huang, summarized what they had discovered in a paper published in the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities.

“We’re trying to characterize racism just in community,” Nguyen said. “To measure some of the social environment characteristics rather than just individual-level experiences, which is important but I think it misses some data points.”

[Read more: Here’s how a UMD student-led drone company is taking flight]

Now, Nguyen and her colleagues are expanding their analysis, pulling in tweets that mention the coronavirus to account for a rise in discrimination against the Asian community.

In the early stages of the project, Nguyen’s team created a list of keywords, which quickly grew to over 500 race-related terms. Using this list, a program pulled out a collection of more than 30 million tweets that included one or more of the monitored words.

Then, using machine learning, the team categorized the compiled tweets as “not negative” — which included positive or neutral tweets — or “negative.” From there, they compared what they found with self-reported cardiovascular disease cases on a state and county level.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States for most racial and ethnic groups, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It became a central point to the team’s research since stress is related to certain risk factors — such as high cholesterol and hypertension — associated with the disease.

Racial bias and discrimination are two things that can increase a person’s stress level, Nguyen said. Over time, a person’s response to this stress can damage their bodily systems and make them more susceptible to cardiovascular disease.

The pattern researchers found was generally consistent, Nguyen said — communities where more racist tweets originated also experienced a higher rate of cardiovascular diseases.

“Environments that have more hostility are associated with worse health,” Nguyen explained.

[Read more: Public health faculty educate about coronavirus at UMD event]

For instance, in Mississippi — where almost half of all race-related tweets collected were found to be negative — there is a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, strokes, heart attacks and other conditions associated with cardiovascular disease. States with more positive race-related tweets, such as Utah, had lower counts of the same conditions by up to 11 percent.

And Nguyen pointed out that the higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease is not isolated to ethnic and racial minorities — people who don’t identify with marginalized groups are also affected. That’s because the social climate is stressful for the population as a whole, Nguyen said.

Olivia Carter-Pokras, another epidemiology and biostatistics professor who studies the relationship between race and health, praised Nguyen’s research. She said the team’s findings add to the evidence that unconscious bias can have a negative impact on health.

“We all have unconscious implicit bias, and we do need to take an active effort to make sure that that doesn’t result in differential care and differential health outcomes,” she said.

Hongjie Liu, chair of the epidemiology and biostatistics department , also spoke positively about the approach Nguyen’s team took in measuring the impact of racism, calling it “innovative.”

Liu said the traditional approach to measuring racism — asking people to self-report whether they have experienced discrimination — does not tell the whole truth. Nguyen and her colleagues, though, measured racism at an environmental level, rather than on a personal level.

“And the finding is very clear,” Liu said. “The environmental level of racism is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.”

Moving forward, Liu hopes the approach Nguyen’s team took will be picked up by researchers in similar fields and used to conduct further public health research.

To Nguyen, the research her team is conducting is a step in the right direction to fully understand what factors influence health.

“We are also recognizing that there is a digital environment,” Nguyen said. “What goes on… digitally and online matters for health too.”