Last year, the World Health Organization declared that the world needs new ways to tackle malaria, a deadly, mosquito-borne disease. Two University of Maryland entomologists — Raymond St. Leger and Brian Lovett — might have found one.

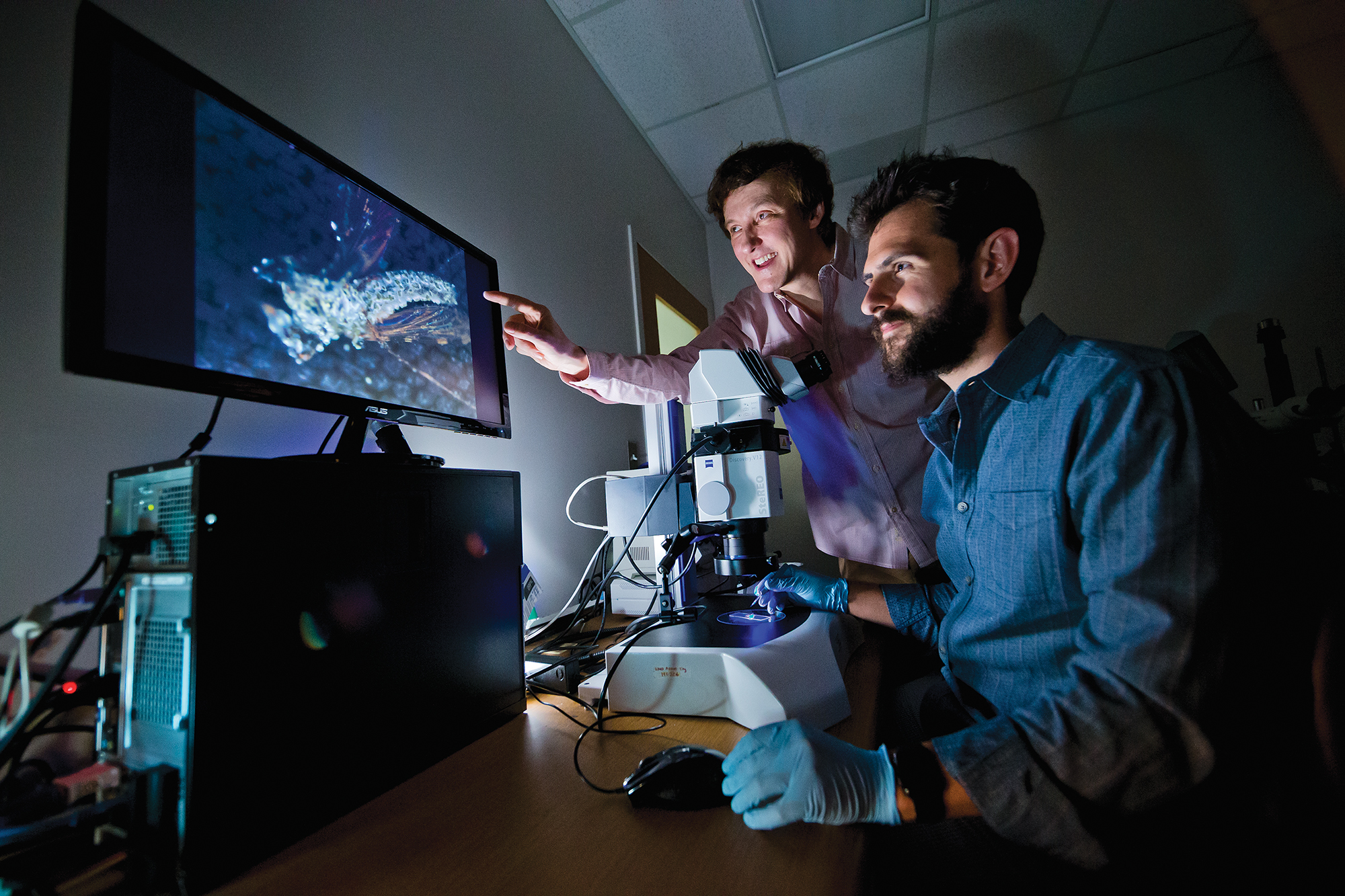

The American Association for the Advancement of Science awarded St. Leger and Lovett its prestigious Newcomb Cleveland Prize for their paper, which detailed how they uncovered a way to kill off insecticide-resistant mosquitoes. Using a toxin found in the venomous Australian Blue Mountain funnel-web spider, the team of researchers reconstructed the toxin’s genetic code, modifying it and adding it to a fungal pathogen that targets mosquitoes. The pathogen would only produce the toxin once it was in the mosquito.

After postdoctoral students developed the genetically modified fungus at this university, the team relocated the study to Burkina Faso, where they conducted the first trial of a transgenic approach to combat malaria tested outside a laboratory. Using sesame oil and black sheeting, they applied the fungus into a 6,550-square-foot structure, which they called MosquitoSphere. It was meant to simulate a rural village, featuring plants and water sources.

“Mosquito population plummeted,” St. Leger said. “It basically wiped out the mosquito population.”

[Read more: RNA research at UMD could give insight on new coronavirus strain]

Eventually, 75 percent of the mosquitoes were infected by the fungus, and the population collapsed within 45 days. This is the first time a transgenic approach, which makes use of genetic modification, has made it this far, St. Leger said. He and Lovett collaborated with researchers at the Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé in Burkina Faso.

Holden Thorp, Science magazine editor in chief and chair of the judging panel, said in a statement that St. Leger’s and Lovett’s research is a new way of approaching the malaria crisis.

“We’re looking for papers that change the way people think about science,” Thorp said. “In terms of the public health, in terms of the science itself, in terms of the way it was rendered, it was a superb study from start to finish.”

Despite efforts to eradicate the disease, malaria infection and death rates have not changed since 2015, according to the World Health Organization. Insecticide-treated mosquito nets, indoor residual spray, diagnostic tests and drugs based on artemisinin were developed to tackle malaria in the last century — and they are still the tools used to tackle malaria today.

The University of Maryland medical school has a research program dedicated to improving malaria treatment and prevention, and on Monday, St. Leger visited the research center to speak about his study.

Professor Joana Carneiro da Silva, who got the chance to talk to him there, said that though the study seems to be a huge development to prevent malaria, she is not sure whether it will be integrated into the ongoing research.

But Carneiro da Silva did see the finding as a step in the right direction.

“If you eliminate the vector, you eliminate [the disease],” Carneiro da Silva said.

[Read more: A UMD student’s research yielded 500 pounds of beans — and a hefty gift to Dining Services]

The program will continue with a wide range of research into therapeutics, intervention, surveillance and preventions through vaccines, said Joanne Morrison, a medical school spokesperson. Lovett and St. Leger are now talking to researchers at the National Institute of Health to discuss next steps.

“We need to show we can actually knock down malaria,” St. Leger said.

Next week, St. Leger and Lovett will go to Seattle to attend the American Association for the Advancement of Science conference. There, they will pick up their awards and meet with possible collaborators, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Over ten years ago, St. Leger was part of a Gates-funded committee researching developments in new technologies for agriculture in Africa and Asia. But they quickly realized that it wouldn’t matter when the health of the people was under attack by chronic diseases like malaria.

Now, St. Leger and Lovett are working with their Burkinabé collaborators and community leaders to develop community engagement plans. They’re also training Burkinabé scientists on the technology.

St. Leger and Lovett are set to discuss further trials to determine if the transgenic fungi could greatly reduce malaria. If further studies are successful, it will be up to communities in Africa to decide if they want to take the work further, St. Leger said, even with the government’s and the World Health Organization’s support.

“At the end of the day, of course, it will be their choice,” St. Leger said.