When people think about Flea, they often think about the rowdy free spirit who plays bass for the Red Hot Chili Peppers. And on the surface, it’s hard to imagine more than that — his completely naked performance during the band’s Woodstock set in 1999 is hard to forget.

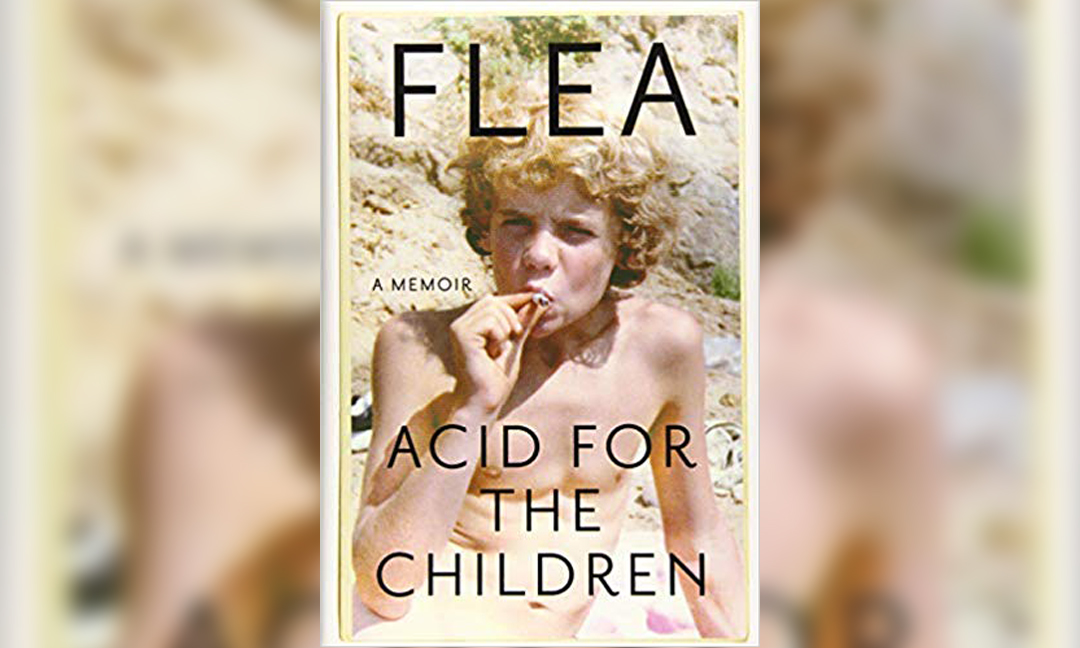

But aside from his outlandish exterior, Flea’s thoughts in interviews and on social media have always intrigued me. When he revealed he was writing a memoir, Acid for the Children, I couldn’t wait to grab a copy. There’s more to Flea than kooky performances, and a memoir is a chance for an artist to highlight a side of themselves many have never seen. In between songs at that same Woodstock set, the bassist exclaimed to the crowd, “I love killer whales, and I love mangoes and Iggy Pop, too!”

When the Red Hot Chili Peppers first catapulted into the Los Angeles rock scene in 1984, their music was more eccentric than the polished Grammy-winning albums they’re known for now. The band’s frontman, Anthony Kiedis, provided a firsthand account of the group’s antics in his 2004 memoir, Scar Tissue. Among them were recording sessions with producer and funk icon George Clinton, paired with $500 worth of cocaine.

I assumed that Flea — formally known as Michael — would provide similar stories in his memoir. How couldn’t I, when the memoir’s cover is a photo of teenage Flea smoking a joint on the beach?

But to my surprise, Acid for the Children concludes just after the Chili Peppers’ first performance. They hadn’t even chosen their name yet. And yet, it feels complete.

[Read more: Review: Taylor Swift’s new documentary shows the pop star like you’ve never seen her]

Flea details the life that led up to that moment — where “four became one” — in a stoic manner. The memoir follows a basic chronological structure, split into three parts: childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. But aside from this structure, Flea exercises a lot of creative freedom throughout the book.

Chapters vary in length, bringing compelling accounts of small childhood moments to life. Flea inserts italicized paragraphs throughout the text, which sometimes work as an extension of his thoughts, or as an author’s note.

A native of Australia, he has a two-page chapter dedicated to the country’s beauty and flaws — and his connection to the land. In a few long-winded, dizzying sentences, Flea explains how a place can hold such beauty yet also terrify him with lethal insects.

He also does an excellent job of reproducing his thoughts as a young child, creating a short list of the main things he thought about as a toddler. The most detailed memory was him imagining his father in the Navy like a sailor in a Looney Tunes cartoon.

Music has been — and will continue to be — a driving force for Flea. It’s sprinkled throughout the memoir in various forms. He includes words mimicking the sounds of the bass, and excerpts from songs at the beginning of certain chapters. He even concludes the book with a list of concerts that changed his life. His enthusiasm to share these musical annotations personalizes the memoir.

Kiedis and Flea have been packaged as a dynamic duo since the Red Hot Chili Peppers entered the spotlight. Flea introduces his longtime friendship with Kiedis by saying nature brought the two together. After calling their friendship “yin and yang, light and dark, beginning and end,” Flea inserts another italicized author’s note of sorts.

The bassist is completely open with readers, describing the difficulty he had writing about this friendship, and his transparency in revealing this decades-long relationship shows his vulnerable side. The fact that Flea felt the need to preface his chapter on Kiedis shows the enormous amount of care he put into it.

[Read more: Maryland student stars in first production of

‘Loserville’ on the East Coast]

Vulnerability, loneliness and the wonder of discovery are key themes in this memoir, and Flea presents difficult stories in a unique light.

When describing his experimentation with shooting cocaine, Flea switches up the chapter’s format. With a typewriter-style font and script format, Flea describes his experience buying syringes at a pharmacy under the guise that he needs them for administering insulin rather than an illicit substance. He commits to his act of pretending he’s just picking up insulin and syringes, like another stop on his wife’s to-do list. His depiction of such a gruesome time of his life helps express the absurdity of it all.

Acid for the Children ends when Flea is just starting his rock career. At age 57, his memoir covers about half of his life, but that doesn’t mean it’s incomplete. He provides a compelling account of the people and experiences that contributed to the person he is today.

In a joking fashion, one of the last pages teases a “Flea Volume Two,” which would answer the many questions that puzzle us to this day, like, “What could rock stardom actually do to a vulnerable human being/guinea pig???” And I’d be happy to tune into volume two.