Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

As a society, we standardize important things such as food safety and emergency procedures — and college admissions. Standardization can be a good thing when people are provided with the resources to meet those standards. However, when it comes to college admissions, standardization will never account for the educational disparities across this nation or for the huge range of applicant backgrounds.

Last week, my colleague Kevin Hu argued that standardized testing should be replaced by a standardized portfolio-based assessment of student ability. Despite acknowledging there are disparities in our education system, his argument still presents forms of standardization as the solution.

Even with a portfolio-based assessment, how can we compare a student who grew up in a low-income community with underfunded schools to a student who attended private schools all their life? These two students would have wildly different experiences; the lower-income student might not have had the educational tools or the time necessary to complete projects with the same quality as a higher income student.

This is an age-old argument — higher education admissions need to be more well-rounded to account for dips in academic achievement and blips in our careers. But well-rounded admissions don’t address how often those issues are linked to systemic racial and socioeconomic inequality.

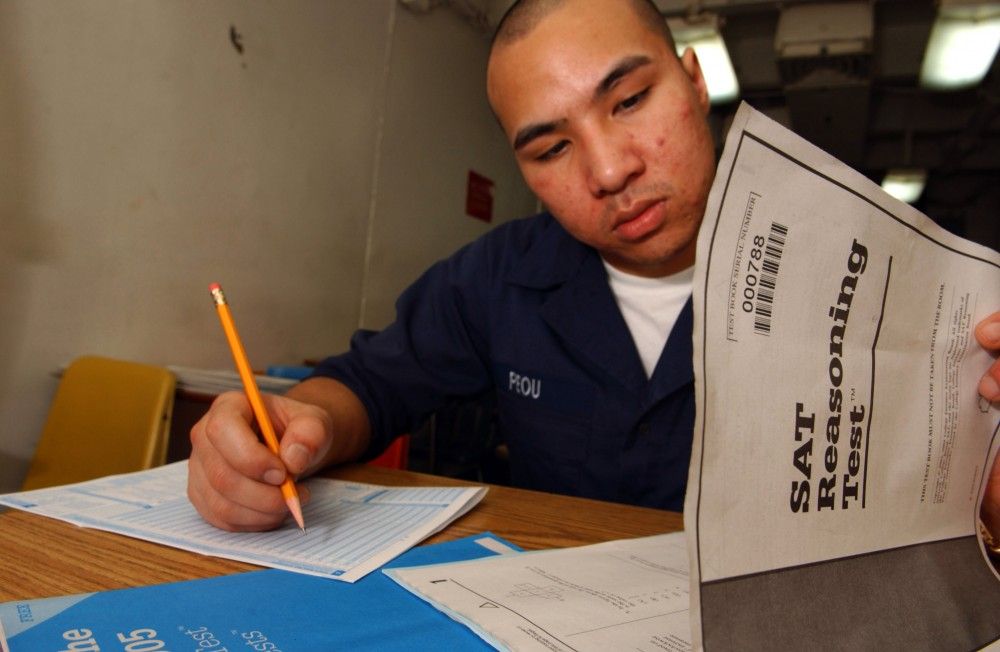

For example, the SAT’s Writing and Language portion focuses on “grammar, vocabulary in context, and editing skills.” But the grammar on the SAT is Standard American English, inherently discriminating against people who speak other dialects of English — such as African American Vernacular English — that have their own grammar and syntax rules.

Would a portfolio-based assessment be able to properly recognize a student who is intelligent, with the ability to think independently, who writes in AAVE? Would it be able to understand that a student who does poorly on math exams and projects went to an underfunded high school with a shortage of math teachers? Or, just like the SAT, would it presume that fluently speaking SAE is an important marker of intelligence?

We can make small revisions to college admissions, but they won’t change the fact that the U.S. education system is inherently racist and classist. At the most basic level, communities of color frequently receive lower education funding than white communities.

In a 2018 report by The Education Trust, it was shown that high poverty districts received about $1,000 less per student than those with low poverty rates. Additionally, districts with the most students of color received approximately $1,800 less per student than districts with the fewest students of color. These structural issues are not in the hands of the students, so students shouldn’t be punished for them. Standardized assessments can’t account for these inequalities, even if they are portfolio-based.

The tasks assessed in the portfolio still rely upon having received a higher standard of education that may not have been possible depending on one’s socioeconomic status. It’s not just a matter of not being able to afford tutoring and supplemental help to pass the SAT, but a result of a structural flaw in our education system that is out of one’s control.

Ultimately, the only way to have a truly “fair” college admissions process is to revolutionize the education system as a whole. There shouldn’t be educational disparities because of one’s socioeconomic status or race — and any standardized assessment that doesn’t account for these systematic issues is placing equality over equity.

Liyanga de Silva is a senior English and women’s studies major. She can be reached at liyanga.a.ds@gmail.com.