Autism research wasn’t on Vibha Sazawal’s radar while she was studying systems engineering and computer science. But things changed after her son, Manoj, was born.

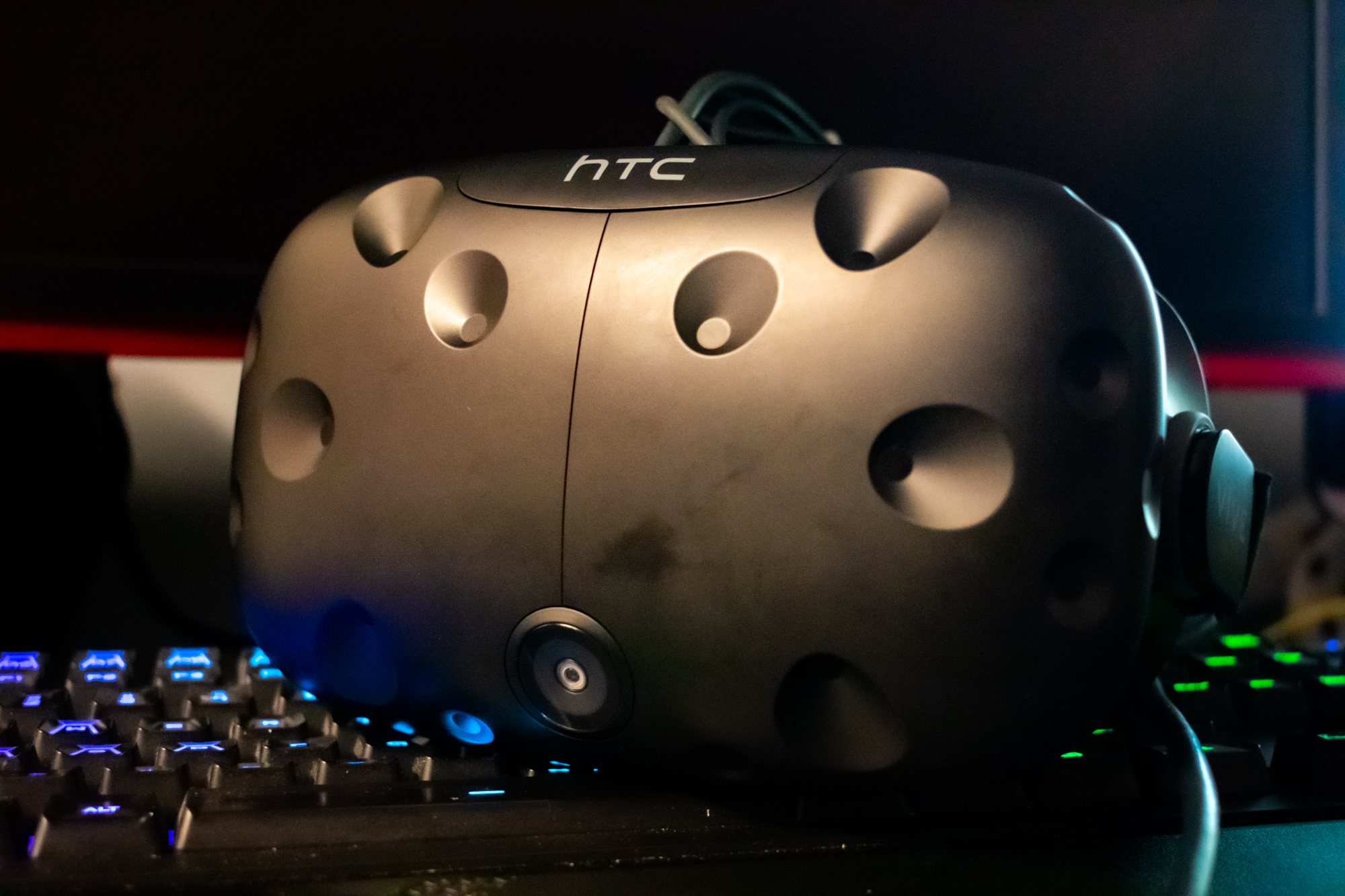

Manoj was diagnosed with autism in 2012, two years after Sazawal quit her job to focus on his needs. And it didn’t take long for him to take an interest in Google Street View and virtual reality, she said.

“This could be a platform that people on the spectrum enjoy,” Sazawal, now a lecturer in the University of Maryland’s computer science department, remembers thinking. “Maybe we should try to use it for something.”

Now, Sazawal is one of the founders of Floreo — a virtual reality application that helps people on the autism spectrum navigate potentially difficult social interactions, including police encounters.

With Floreo, users are able to work their way up a scale of increasingly challenging police interactions, as a facilitator controls the scene. They can start out in broad daylight, for example, and shift toward night scenes with loud sirens.

Knowing how to communicate with police officers is a form of self-advocacy, said Kathy Dow-Burger, founder of the Social Interaction Group Network. The group, supervised by faculty at this university’s Autism Research Consortium and hearing and speech sciences department, is designed to build comfort and confidence in its neurodiverse members.

“When you think of the autism spectrum,” Dow-Burger said, “It’s not like everybody’s the same.”

[Read more: Neurodiverse students at UMD encounter challenges while job-hunting]

Individual ability to use and understand language vary from person to person, Dow-Burger said. Sometimes, a person on the spectrum might not comprehend they are being spoken to, which can lead to misinterpretation.

There are also differences in sensory processing among people with autism and other developmental disabilities, Sazawal said. Some individuals might be sensitive to noise, others might be under-responsive, and still others might have a “mixed profile.”

In the case of police encounters, especially, this can be dangerous.

“Interacting with police, fire department, any kind of first responder, is a really important skill,” said Judith Miller, the clinical training director at the Center for Autism Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “It’s one of those things that doesn’t happen very often, and it’s usually stressful.”

In 2013, Ethan Saylor, a Frederick County man who had Down syndrome, died after an interaction with off-duty sheriff’s deputies in a movie theater. He had tried to walk in without a ticket, and — according to a civil lawsuit filed by his family — the guards dragged him out despite his screams of pain. He stopped breathing, and though his death was ruled a homicide, the deputies were cleared of criminal charges.

[Read more: UMD no longer recycles glass. Here’s why.]

According to a 2016 study by the Ruderman Family Foundation, a private philanthropic group, people with disabilities make up between a third and a half of all people killed by police.

Miller, a research partner with Floreo, is currently working on a study on its efficacy, focusing on teenagers’ and adults’ interactions with law enforcement through the app.

Sazawal first set her son up with a virtual reality headset when he was seven. He loved it, she said, quickly adapting and eager to interact with every character he discovered there.

Manoj had already mastered some of the skills offered in the first prototype — which included exercises dealing with attention and focus — so he wasn’t learning anything new. The police safety modules, though, were something that Manoj hadn’t encountered before.

“That’s another thing that VR makes so great — because it’s very hard for us to simplify the real world,” Sazawal said.

By now, though, Manoj has had experiences with lots of police officers, since they’ve worked with them for Floreo, Sazawal said. She said he’s “thriving,” and whenever he comes along to a Floreo outreach event, he’s encouraging other kids to try it.

Though Sazawal said she wished training like Floreo weren’t necessary, she’s glad that the technology has the potential to make law enforcement interactions easier for people with autism.

“In an ideal world, you have this kind of autism acceptance, where people can just be who they are,” Sazawal said. “But in the real world, you know, it’s dangerous.”