Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

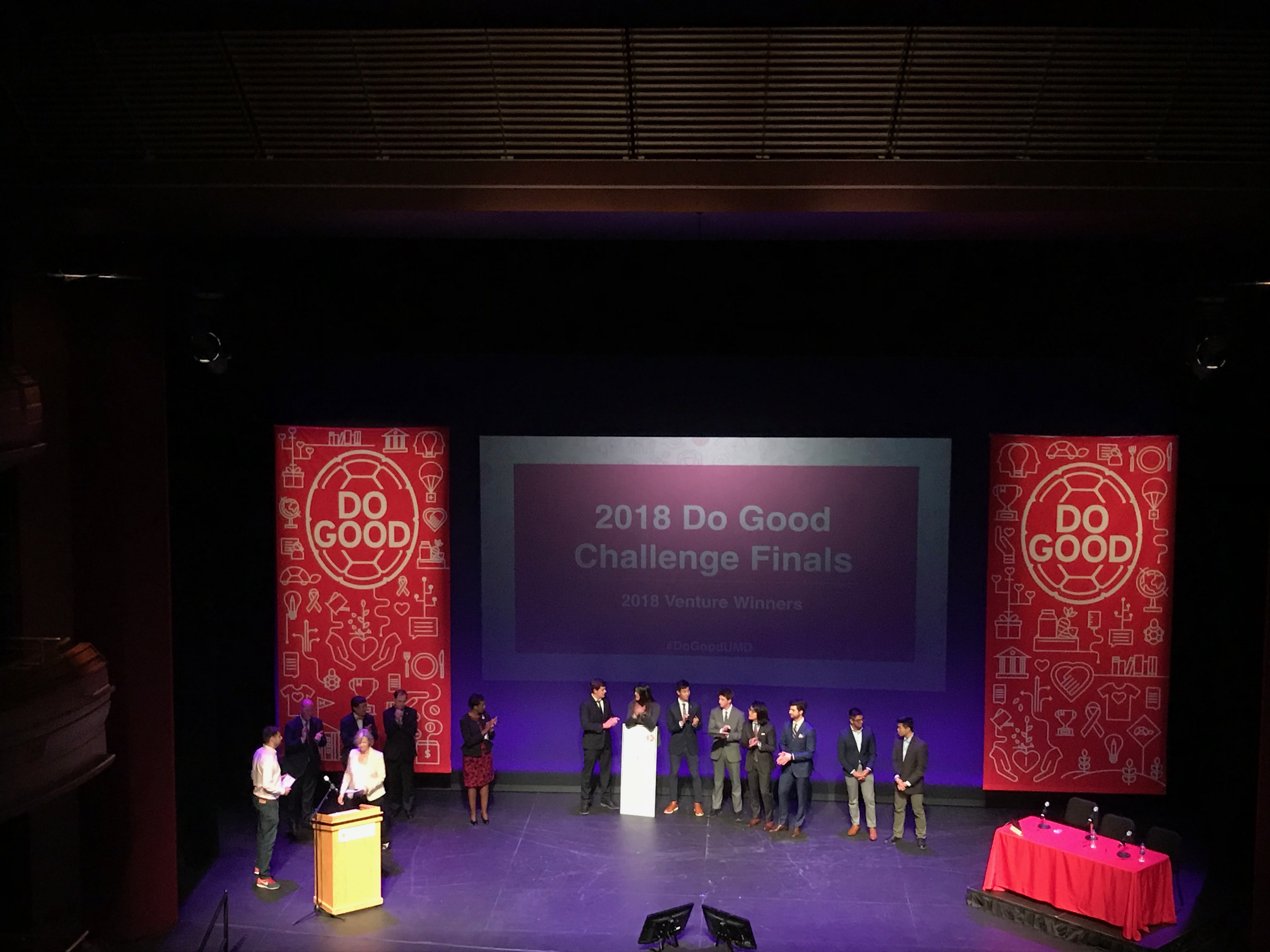

In another University of Maryland PR stunt, the Do Good Institute is hosting the Do Good Challenge finals on Thursday. Launched in 2014, the Do Good Challenge “inspires students to take fearless ideas, spark innovative solutions, and create social impact for today’s most pressing problems,” according to its website.

In the Do Good Challenge, students form teams to design and “make the greatest social impact they can for their favorite cause.” They then pitch their solution in front of a panel of judges, including a past winner of the challenge. If the judges deem a team’s pitch worthy, they award it up to $5,000 in funding, benevolently doled out by corporate sponsor Morgan Stanley Private Wealth Management.

In the course students can take to get credit for participating in the challenge, students attempt to apply “design thinking” to tackle their “favorite” social problems. In the design thinking model, students are directed to conduct interviews to empathize with their users, then define the problem, ideate innovative solutions, test out a prototype and refine the design.

But nice-sounding procedures like “ideation sessions” and “empathy interviews” with prospective clients portray the designer’s ideas — not those of the people they claim to help — as paramount and encourage participating students to project their own priorities onto people they are trying to serve.

Competing for scraps given out by one of the largest investment banks in the nation — which earned its wealth through serving corporations and the affluent and has fostered a culture of discrimination and abuse — affirms a morally bankrupt assumption that redistributing wealth to hand-picked charities excuses the corrupt means through which that wealth was accumulated.

The challenge only encourages students to engage in superficial, short-term projects. It doesn’t get students to examine the root causes of inequality or critique the reasons why the institutions they’re investing in don’t have resources in the first place.

When I was a student in the course, my professors encouraged my team to start a project in which we merely dropped off used Maryland apparel to a community center. We did not contact the community center staff after the course ended, nor were we encouraged to engage in any follow-up or evaluation of our impact. We were simply patted on the back and sent away with another line to add to our resumes.

Raising some money for a hospital, designing a mental health resource app or dropping off recovered dining hall food might make some students feel good and may benefit some individuals. But the projects are restricted to the narrow framework of the Do Good Challenge, which refuses to address social issues on a structural level. As a result, they’re often little more than superficial gestures that fail to advance substantive change.

To truly do good, the university should teach students organizing skills and activist tactics, providing course credit and excused absences to students participating in mass movements or leading organizations that radically challenge the status quo. The university should teach students to lobby elected officials to make college free, cancel student debt, pay teachers and teaching assistants living wages, hold police officers accountable, divest from unjust corporations — or any number of other things that would fundamentally restructure our society’s resource distribution.

By teaching us how to superficially brand ourselves as do-gooders and participate in an inadequate, short-term approach that is fundamentally incompatible with achieving lasting change, this university is doing harm.

Olivia Delaplaine is a senior government and politics major. She can be reached at odelaplaine15@gmail.com.