The Philippines has been a cornerstone of United States foreign policy in Asia since the late 19th century. Despite a volatile early history between our two nations, including a three-year insurgency following U.S. colonization, the view of America on the island nation today is rather positive. In June 2015, Pew Research Center reported on America’s trending image across the world, and in the Philippines, the U.S. earned its highest favorability rating of 92 percent. Even as recently as January 2016, the Philippines agreed to increase U.S. military posturing on the island in defense of shared interests in the South China Sea. Yet despite our historical alliance, Filipino president Rodrigo Duterte doesn’t seem to mind testing the limits of acceptable comments. In September, Duterte made headlines when he denounced President Obama as a “son of a bitch” in response to American criticism of his domestic policies, prompting Obama to cancel an upcoming meeting with the Filipino leader. Such incidents exhaust our bilateral cooperation, and as Duterte feels increasingly alienated by the West, he’ll attempt a pivot toward China. In fact, Duterte has already explicitly stated this.

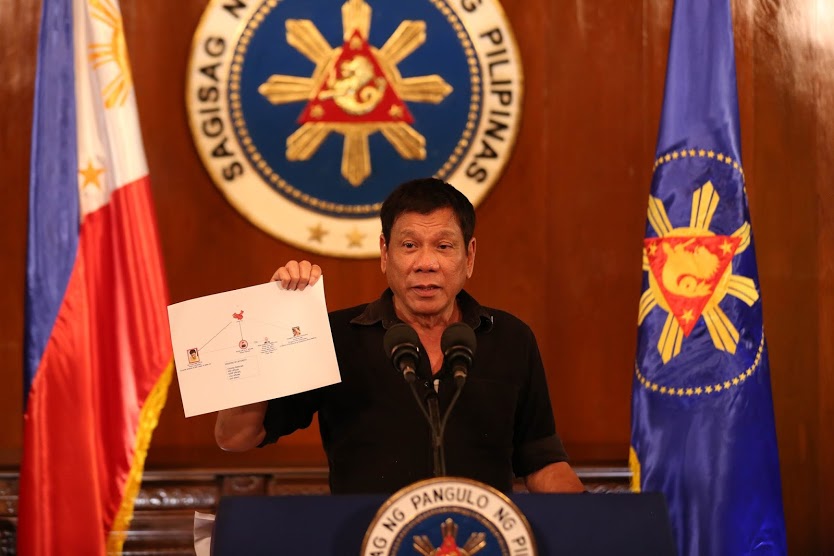

Recently, the Obama administration has been critical of Duterte’s violent crackdown on drug use in the Philippines — a crackdown that has already resulted in an estimated 3,000 extrajudicial killings. Unfortunately, stern words from abroad have only further emboldened him. The Associated Press reported on a recent speech in Manila, where Duterte warned of a split with American interests, and a possible alliance with Russia and China. Indeed, based on his diplomatic itinerary involving an upcoming trip to China with Filipino business leaders, he’s already moving to find new economic partners. Duterte may very well sever our century-long partnership, but if that’s his intention, he’s gambling with how other Asian partners and even his own people will receive such a move, not just the U.S.

China’s increasing aggression in the South China Sea has been met with paralleled aggression from other Southeast Asian nations. Territorial disputes in The Hague and increased maritime patrols in the region have garnered concern over an encroaching China. The South China Sea is strategic for two primary reasons: uninhabited archipelagos rich in natural resources and a trade route valued at $5 trillion each year. As it stands, The Hague rejected China’s claims to the entirety of the sea this summer. Additionally, member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations have cozied up to the idea of American partnership to deter China. Prior to Duterte’s presidency, the Philippines was among them. As a primary plaintiff in the case brought before The Hague, it seems counterintuitive for Duterte to rally behind China now. However, even if he’s successful in securing trade deals with China that his constituents approve of, he still must deal with the consequences of alienating not only American interests, but also other allies in the region.

In Vietnam, relations with the West have been warming for some time. Increased naval partnerships and growing American investment in their security and defense industry have proven popular to the Vietnamese people. Earlier this year, Obama visited Vietnam to announce an end to the arms embargo on the country that has been in place since the Cold War, a relic of policy-making from a time when American and Vietnamese relations were diametrically opposed. Vietnam, South Korea, and Japan, are all becoming ardent allies to counter the growing clout of China. The failure of the Philippines to get on board will have a negative impact on their relations with ASEAN member states.

Of course, there remains the chance that the Filipino people themselves will reject Duterte’s severing of diplomatic ties with the U.S. Even today, America and the Philippines share a unique set of cultural ties. After all, Filipinos make up the second-largest Asian-American population in the U.S., and the largest portion of foreign-born U.S. military personnel, according to a report by the Congressional Research Service. This too doesn’t bode well for Duterte’s ambition. In the end his people may reject the dramatic shift to the Chinese sphere of influence, and in doing so, reject him.

Kyle Rempfer is a sophomore government & politics and Russian major. He can be reached at krempfer@terpmail.umd.edu.