The University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s oyster hatchery will help plant more than one billion oysters in the Chesapeake Bay to improve its health next summer, said Don Meritt, the head of the center’s Horn Point Lab Oyster Hatchery.

Oyster populations in the Chesapeake Bay have decreased rapidly over the past several decades, said Stephanie Westby, an oyster restoration coordinator working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Chesapeake Bay office. As of this year, one percent of the historic levels of oysters are left in the bay, she said.

In efforts to curb this decline, NOAA awarded the Maryland Natural Resources Department an $800,000 cooperative agreement, which is similar to a grant, but it allows donors to be involved in the project, according to the National Institute of Justice. The funding was publicly announced at the end of August, but it becomes available at the beginning of the next fiscal year on Oct. 1, said David Blazer, fisheries director for the state’s Natural Resources Department.

The Maryland Natural Resources Department subcontracted the hatchery and the nonprofit organization Oyster Recovery Partnership, which will help plant the oysters next summer, Westby said.

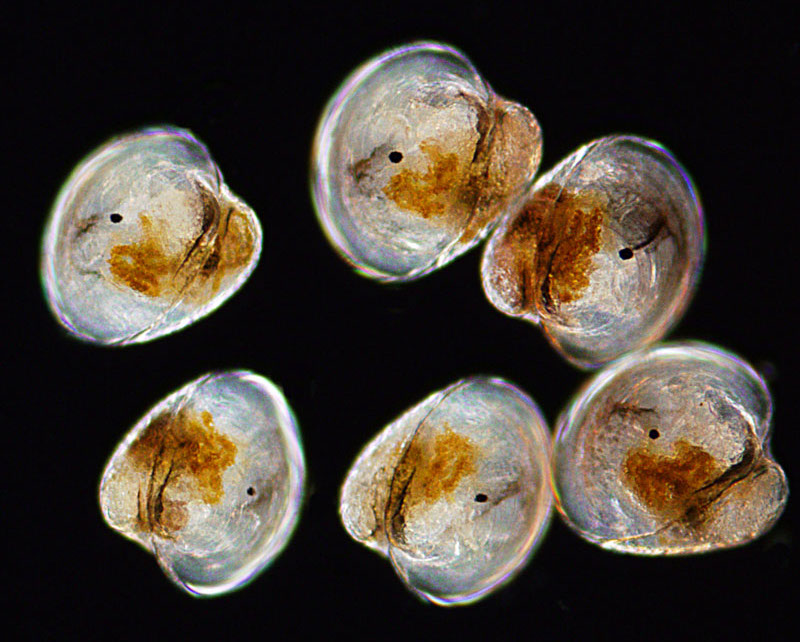

The hatchery was chosen because it’s the only hatchery in the state, Meritt said. It’s also the largest hatchery in the world for this species of oyster, he said.

In areas with reefs that are still intact, the oysters will increase remaining populations. However, the Oyster Recovery Partnership will need to rebuild inhabitable reefs, Westby said. They’ll use stone, concrete or old oyster shells to do so, she added.

Their reefs also provide habitats for a wide variety of other marine life, Meritt said.

Oysters, which are filter feeders that clean the water around them, are “a critical component of a healthy bay system,” Meritt said. “Generally the other species on the oyster reefs increase with a healthy oyster population.”

A bay overpopulated with oysters, “would be a nice problem to have,” Blazer said.

Oysters have been missing from the Chesapeake for so long the ecology of the bay was “thrown out of wack,” Blazer said, and bringing them back will increase populations of other species.

The project-bred oysters will be placed in the rivers and creeks the partnership has listed as sanctuaries. Hopefully, Westby said, these new oysters will repopulate enough to spread beyond the sanctuaries and benefit the commercial harvest as well.

“Realistically we’ll never get back to that … level but we’re trying to make it better than what we’ve got now,” Westby said.

Correction: Due to a reporting error, a previous version of this story incorrectly stated that the Horn Point Laboratory is a part of the University of Maryland. The University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science is an independent member of the University System of Maryland. This story has been updated.