Hurricane Katrina’s receding waters revealed more than destruction, layers of mud and dead bodies, black leaders say. Underneath the ruin of a natural disaster lies a devastating reminder of overlooked poverty and a strong racial divide.

At the Black Student Union’s first general body meeting last night, several executive board members wore black ribbons on their shirts in support of hurricane victims as students expressed grave concern at how federal response and media coverage of Katrina differed based on race.

A rising death toll and the widespread belief that the federal government could have done more to help victims of Katrina, which wreaked havoc on Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, have angered many, particularly in the black community.

Ron Walters, a government and politics professor and director of the African American Leadership Institute, said blacks have a right to be angry.

“I think that race was certainly one of the factors involved. I don’t think it was the only one. It was inescapable. You couldn’t miss it from the press coverage,” he said.

But, Walters added, this anger has mobilized black Americans to address racism and poverty.

Jessica Gordon Nembhard, economist and assistant professor in the department of African American studies, agrees.

“This is the first time in a long time that we’ve actually talked about race and class,” Gordon Nembhard said. “It’s also given us a way to talk about how important that whole region is to African American history and culture.”

Gordon Nembhard, who described the federal government’s response to Katrina as “extremely and disturbingly slow,” attributed much of the perceived racial bias to “institutional racism” and noted a large number of Americans do not see these biases.

“A lot of it is built into the system,” Gordon Nembhard said. “Decades of overt and covert discrimination whose effects such as poor quality education and high unemployment have cumulative negative impacts on non-whites over generations, at the same time that whites receive cumulative benefits.”

Clyde Woods, an assistant professor in the African American studies department, said the hurricane and its aftermath has particularly moved black Americans.

“They realized they had forgotten about the South. They just forgot about it – they forgot that black poverty defines America. It defines everybody in the black community. The South is still the heartland of the black identity – it really touches African Americans. It’s calling into question a lot of African American institutions.”

Last Thursday, Woods and other faculty members met with student leaders to discuss ways to contribute to the relief effort.

Hank Rawlerson, president of the Black Student Union, said he felt the criminal aspect of Katrina’s aftermath – fear of looting, gangs and violent activity – was often emphasized, both by the media and President Bush, more than the destruction the hurricane caused. He said he feared the focus on crime and government response, which he believes was more about restoring order than helping people, took away from the relief effort.

“The people – watching television, who can’t put themselves in [the victim’s] situation, look at the [victims] … as criminals. It gets rid of their empathy – makes them not want to help. It’s just the way that [blacks] have been portrayed forever. ‘Black’ in this country has become a synonym for crime – especially ‘poor and black,'” Rawlerson added.

Many have cited inconsistencies in news coverage of white and black victims. For example, one photo described two white victims as wading through water after “finding bread and soda,” while a similar one described a young black man as “looting.”

Despite being captioned and released by two separate news organizations – the former was an AFP/Getty Images photo, the latter was released by the Associated Press – the two photos appeared side by side on Yahoo news, and then landed on Internet blogs and media websites, accompanied by questions and speculation as to whether the distinction was racially motivated.

A Sept. 8 survey by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, an opinion research group that studies public attitudes toward the media and public policy, showed a large division between black and white attitudes surrounding preparation for the hurricane and relief effort.

Eleven percent of black Americans surveyed said they felt Bush did all he could to expedite the relief effort, compared to 31 percent of whites. Sixty-six percent of blacks said they felt the response would have been faster had more white people been affected, compared to 17 percent of whites. Seventy-one percent of blacks felt federal response proved racial inequality to still be a “major problem,” compared to 32 percent of whites.

Jaimar Staples, a freshman sociology major from Prince George’s County, said he thought the federal government’s response to the hurricane brought “attention to the fact that racism still exists in America.”

“I’ve talked to a lot of my white friends and they don’t see racism as a big deal,” he added.

Raheem Dawodu, president of the university’s NAACP chapter, said the black community’s next step is to put pressure on the local governments in areas affected by Katrina, as well as the federal government, raising questions.

“After that we can go from there and find policy we can initiate,” Dawodu said. “First and foremost, we’ve got to ask questions. Why are these people so far behind? Why didn’t we do anything to help?”

“It’s troubling and disgusting that these people were forced to fend for themselves. It really doesn’t make sense to me how this happened,” he added.

Jake Levin, a senior secondary education and history major from Columbia, said while the handling of Hurricane Katrina may have brought racial tension to light, now may not be the right time to address these issues.

“Help for the evacuees, finding survivors and taking care of the dead needs to be priority. It looks like it might be much more that it was a poor city than that it was a black city,” Levin said.

But Walters said the relief effort needs to go hand in hand with an assessment of racial inequality.

“I don’t think that this is something that you can push aside. This has been the same response again for two decades. I think that there is an order of things – relocation, resettlement, redevelopment – those things are upmost in everybody’s mind but these things have to run concurrently.”

Gordon Nembhard said both race and class issues should be addressed and the government needs to determine who is accountable for any mistakes made. But most importantly, she said, the country needs to recognize what the residents of the affected cities have been through.

“We have to think more about ways to show the dignity and the heroism of the victims and the survivors. I think that gets lost sometimes. We often don’t think of poor people or people of color as being heroic.”

Contact reporter Bethonie Butler at newsdesk@dbk.umd.edu.

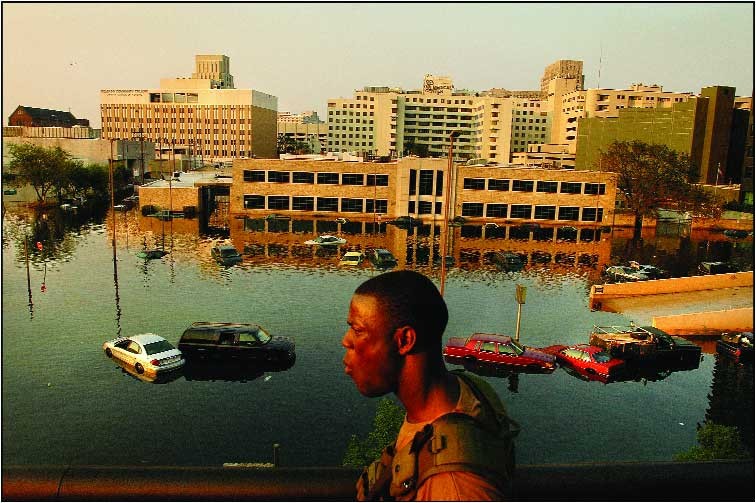

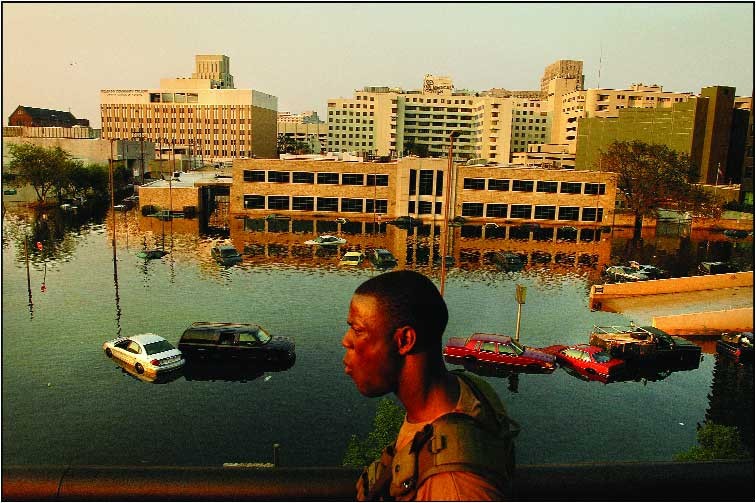

Sgt. Rodney Antoine of the 159th Squadron stands watch outside of the evacuated Superdome in New Orleans.

Air Force troops moved in to secure and evacuate New Orleans residents following Hurricane Katrina. The images in news reports that showed that a majority of those left behind in New Orleans were black and many were poor has ignited race discussions natio