This past week, more than a hundred major media organizations (through guidance from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists) released a collection of stories about the “Panama Papers,” a series of leaked information detailing nefarious tax-dodging mechanisms orchestrated by one of the world’s leading global legal corporations, Mossack Fonseca.

This tidal wave of damning financial information included assets related to public figures reportedly ranging from Russian President Vladimir Putin to Argentine soccer star Lionel Messi, sweeping up 12 national leaders and 143 other major politicians in the process. However, the revelation that this extensive network of tax evasion and fiscal deviancy even exists might prove less significant than the process by which it was discovered.

Ever since the onset of large-scale globalization in the 19th and 20th centuries, the world’s rich and powerful have utilized access to international investment as a means of circumventing domestic financial responsibility. Increased economic ties between previously isolated countries offered an exclusive advantage to those people and corporations wealthy enough to exploit them: tax shelters.

Due to differences in corporate, capital gains and personal income taxes, oligarchs and the conglomerates they run often employ shell subsidiaries (companies which serve as vehicles for business transactions without having any significant assets or operations) to move their corporate headquarters overseas. For example, a single building in the Cayman Islands is the registered corporate address for 18,857 different companies, as their government levies no corporate taxes on businesses operating there. While this process costs the U.S. alone more than $100 billion in lost tax revenue per year, the numbers appear even more staggering on a global scale.

Experts estimate that between $21 and $32 trillion of private financial wealth was hidden in tax shelters by the end of 2010, more than the entire GDPs of the U.S. and Japan combined based on purchasing power parity. Even more discouragingly, this practice results in what economists call a “tax incidence,” or a shift in the distribution of economic welfare via tax policy, falling on the middle and lower classes. In other words, the rich have an institutionalized monetary advantage through tax shelters that they use so effectively and promiscuously that they have forced the poor to have an outsized tax responsibility compared to their modest wealth.

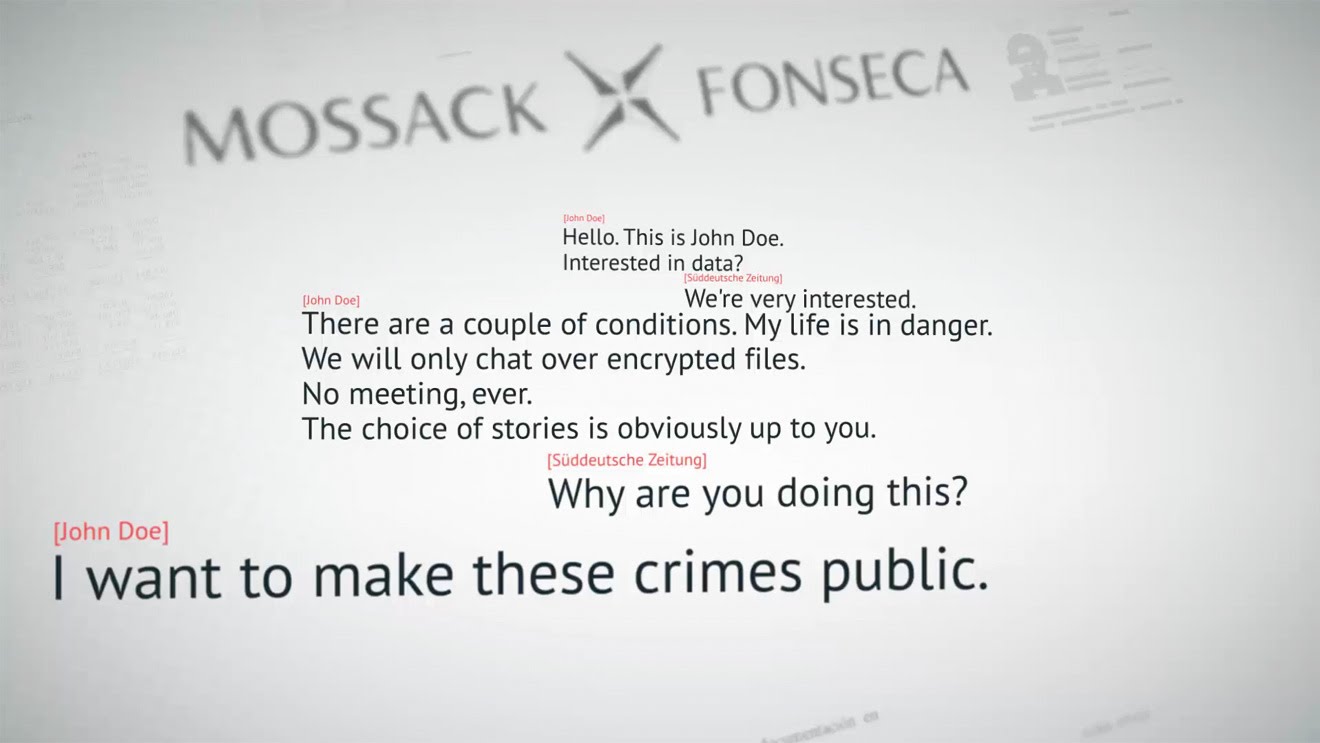

But while expanding economic globalization has contributed to the rise of a previously unassailable oligarchic class, increasing information-technology globalization has also begun to accelerate its downfall. In 1969, disenfranchised former State Department employee Daniel Ellsberg photocopied 7,000 pages of classified documents relating to the U.S. government’s involvement in the Vietnam War, then delivered them by hand to The New York Times two years later. These documents, known as the Pentagon Papers, helped amplify anti-war sentiment among the American public. However, as a result of the inefficient methods of acquisition and transmission, this large-scale leak was only plausible in a major industrialized country. The odds of any employees of a Panamanian law firm having either the resources to acquire, or the connections to transmit, this amount of information at the time seem highly unlikely. Now fast forward to 2014, when a single encrypted chat message to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung sparks a 2.6 terabyte, 4.8 million email mega-leak, the contents of which are swiftly dispersed to more than 400 journalists worldwide.

This international electronic coalition spends more than a year sifting through the massive amounts of data, as a search engine, database and live chat spring up to guide any reporter in need of assistance. This level of global cooperation and technology-based reporting allowed the media nearly unfettered access to one of the world’s most secretive institutions, and brings to light corruption with a remarkable level of scope and clarity.

In past decades, the economic benefits of globalization could only be reaped by those with enough economic clout to access them, unleashing a shadow economy solely dedicated to hiding money overseas. Now, through advances in technology, these same forces of interconnectivity which allowed the wealthy and elite to construct vast fortresses of tax evasion and legal loopholes have now begun to permeate the very mazes of monetary fraud they helped build.

Reuven Banks is a freshman enrolled in letters and sciences. He can be reached at rbanksdbk@gmail.com.