Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

U.S. President Donald Trump has been on the warpath of injuring every major trade relation the country holds. Recently, he paused proposed tariffs of 25 percent on goods from Canada and Mexico. Trump continued his promised “Liberation Day” via tariffs last week by announcing a 25 percent auto tariff on car parts imported from other countries, which is expected to be implemented by May 3.

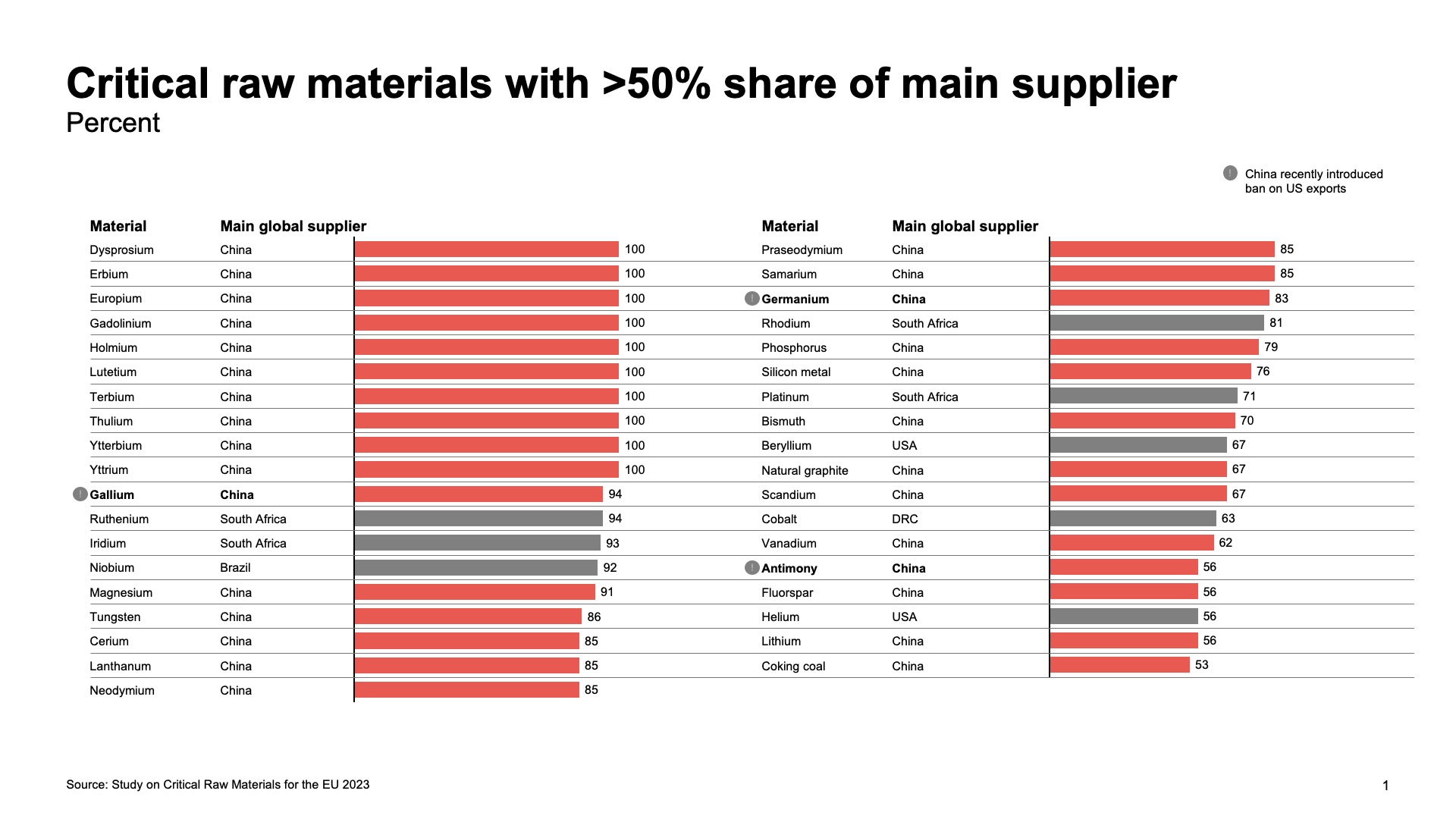

While all of Trump’s proposed tariffs pose significant ramifications for Americans, one that may be most alarming targets the United States. In December 2024, China announced a ban on exporting gallium, germanium and antimony to the U.S. These three elements are essential for technologies such as solar cells, batteries, medicines, LCD and OLED displays and integrated circuits.

China’s export ban of these critical materials pose significant risks to the U.S. economy, technological advancement and national security. These risks are exacerbated by the U.S.’ overdependence on importing these materials.

If the U.S. is going to remain competitive in technological areas such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence, it must develop the necessary facilities to mine and process key materials, such as gallium, domestically.

China is the world’s largest supplier of critical raw materials, which are used across multiple industries. Gallium is one of these, and is used for radio frequency electronics, power electronics, photonics, light-emitting diodes and solar cells.

The U.S.’ problem is twofold: lack of domestic supply and lack of necessary facilities to process critical materials. Investment from the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act will likely lead to increased development, but the focus so far has only been on processing facilities.

The bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act led to investment in developing semiconductor supply chains in the U.S. As a result, the U.S. commerce department announced in 2022 a plan to build 16 new semiconductor manufacturing facilities. The commerce department previously said it expects the U.S. will produce nearly 30 percent of the world’s computer chips in 2032.

With federal budget slashes, including the recent firing of the now-reinstated nuclear weapons staff, it’s likely the Trump administration will also attempt to cut investment in critical materials.

While semiconductor production was set to rebound by 2024, there has been a continued shortage to support a growing market that is likely to experience further shortages throughout 2025. Due to high demand in the industry, increasing dependency on capital markets and technological demand, the need for critical materials is increasing and the U.S. continues to lag behind China.

Countering China’s dominance on critical elements may be impossible without continued investment given the ever-increasing demand. Even the European Union sources most of its critical materials — including as much as 98 percent of imported rare earth minerals — from China.

Addressing the insecurities created by over dependence on China as a supplier and processor of critical materials can only be countered by investing more in mining development and domestic processing. While the CHIPS Act achieved some positive counterbalancing of China’s dominance, more mining sites must be located, developed and fully operational as early as 2030.

Failure to develop more mining facilities will likely exacerbate China’s dominance due to lacking a sufficient supply of key materials to meet the U.S.’ needs. By not developing mines domestically, the U.S. risks pushing allies toward Chinese dependency, while also failing their own at home.

The critical material export ban to the U.S. will hinder military and technological advancement that is often dependent upon them. These actions will further weaken the U.S. as a hegemonic power and may lead to unexpected challengers given the current volatile policy climate.

For the U.S. to remain competitive in the technology industry, including in artificial intelligence, Congress and the executive administration need to push for allocations of funds to support investment in critical material acquisition and processing, not semiconductor facilities alone.

Autumn Perkey is a government and politics doctoral student. She can be reached at perkey@umd.edu.