Content warning: This story contains explicit mention of violence and death.

University of Maryland community members learned how art is used to heal from trauma in a Thursday screening of “Las Muertes Más Bellas del Mundo,” a story of Salvadoran artists who found sanctuary in Washington, D.C., after fleeing the El Salvador civil war.

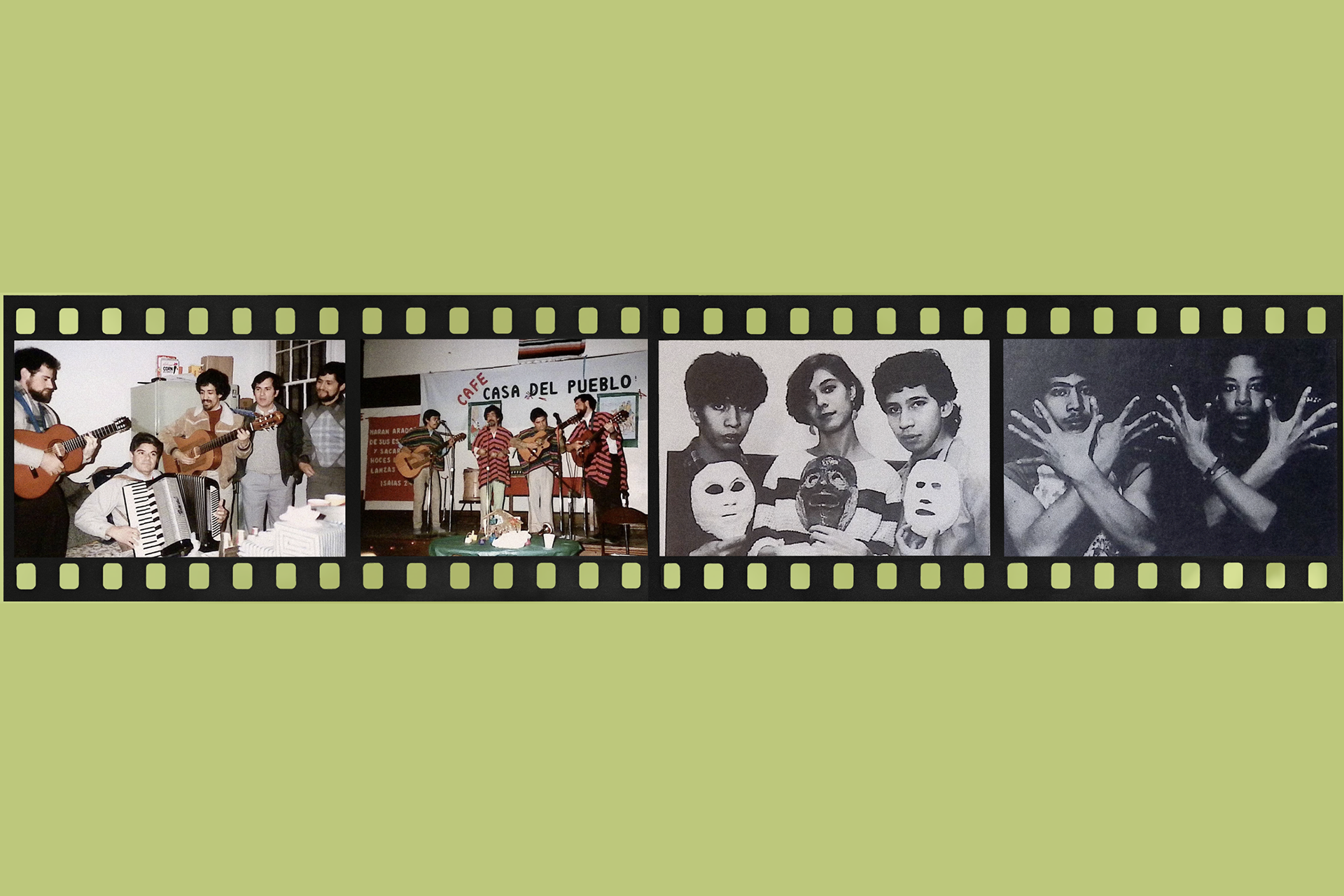

The documentary screening, hosted by the languages, literatures and cultures school and multiple co-sponsors, also featured a panel discussion with its featured artists as part of Latine Heritage Month. Through personal interviews, archival images and grainy videos, viewers follow artists as they explore the intergenerational traumas in Washington, D.C.’s Salvadoran community.

[Zine Club relaunch invites students to create, connect through design]

The Salvadoran Civil War killed more than 75,000 people — mainly civilians — according to Encyclopedia Britannica. Guerilla forces fought against the U.S.-backed El Salvador military forces after years of increased human rights abuses, according to the encyclopedia.

Poet Quique Avilés, one of the documentary’s directors, said the Salvadoran military invaded his town and killed civilians involved in the leftist movement before he left for the U.S. with his grandmother.

Avilés later learned that many of his family members and childhood friends were killed in the war, he said. Forty years after he left, Avilés returned to El Salvador to search for his dead relatives and complete a poem about his wartime experiences — one he struggled to recite in the film.

“Have you seen Chamba, Esmeralda, Noemi? How many did they kill last night? Where did they dump them? Please lead me to the bodies,” the poem read.

According to Avilés, the film intended to teach a new generation of Salvadorans who might not have learned about the war’s resulting trauma.

Brenda Merino, a senior economics major and screening attendee, first learned about the Salvadoran Civil War when she asked her parents about it two years ago for a class assignment. Merino said some of her parents’ friends were also killed in the civil war.

“It was pretty normal for everyone to know people that have died,” Merino said as she wiped her tears. “My parents are in their 40s and 50s. They’re still here and they lived through that so I think it’s very important to highlight what they went through.”

The documentary also allowed Salvadorans to mourn as many were stripped of the ability to say goodbye to their loved ones, Ana Patricia Rodríguez, a Salvadoran and an associate professor in the Spanish and Portuguese department of the languages, literatures and cultures school, said.

[Charli xcx drops another set of club classics on ‘Brat’ remix album]

Many people who migrated are undocumented, Rodríguez added, which means they can’t return to El Salvador.

Avilés said art is an outlet for telling El Salvador’s story because it allows people to express things they wouldn’t be able to convey through a regular conversation.

One of the documentary’s subjects, Flamenco dancer Edwin Aparicio, used dance to process political turmoil in Washington, D.C., in the 1990s. Muriel Hasbun, another documentary subject, turned to photography to explore her roots and her family’s diasporas, through the lens of her camera to try to understand their traumas.

Alirio Gonzalez created a rock band in an effort to express himself.

“My anger, my trauma. It comes out through the way I play the guitar, the way I write the songs,” Gonzalez said in the film.

In the documentary’s final scenes, Avilés completed his poem after he put his dead relatives to rest beside a river in his hometown.

“I find one, then another one, and I do what any decent human being would do in front of a dead loved one. I kiss them. I hug them,” Avilés said. “I wash them … I give them a new baptism and I give them names that are beautiful. I give them dignity.”