Editor’s note:

A previous version of this story used a quote provided in a Prince George’s County Council press release without attributing it to the press release. This misattribution did not meet The Diamondback’s editorial standards and the story has been updated. We regret the error.

The Prince George’s County Council held a town hall meeting Tuesday to gather feedback about residents’ experiences seeking mental health assistance and resources amid an ongoing “mental health crisis” in the county.

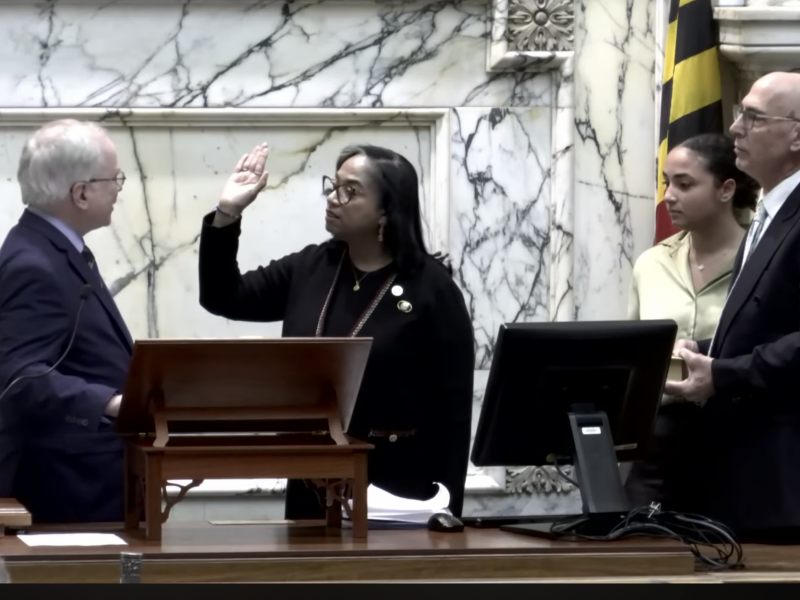

The event, hosted by District 6 council member and health board chair Wala Blegay, drew multiple county residents hoping to find solutions to the crisis and offer support to those in need.

“We are experiencing a mental health crisis, and many are suffering in silence,” Blegay said in a release on Nov. 2. “There are gaping holes addressing mental health in this county and we want to change that.”

Prince George’s County has seen an increase in reported mental health challenges in recent years. In 2018, almost one in five high school students in the county reported contemplating suicide, according to the Prince George’s County Department of Health.

The health department introduced several programs focused on children, families and individuals at risk. This year, the department has trained 40 mental health professionals from schools and behavioral providers across the county in Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy — a type of trauma intervention geared toward children, youth and families.

Laurel Medical Center, a new University of Maryland Medical System hospital located in the county, will also see a new mental health program for adolescents through startup funding. The Adolescent Partial Hospital Program is designed to provide comprehensive care and support for adolescents, according to a presentation at the town hall.

[Prince George’s County cannabis reinvestment board aims to address inequities]

Matthew Levy, the county health department’s director, emphasized the county’s ongoing commitment to expanding its mental health programs.

“Whatever we have is not enough,” Levy said. “We are building more things and trying to develop more programs to address and help the community and all the mental health and substance use disorder needs of the community.”

Council members and county residents voiced concerns about shortcomings in addressing mental health issues in Prince George’s County.

District 3 council member Eric Olson emphasized the shortage of inpatient beds for children in the county who require mental health treatment.

The University of Maryland Capital Region Medical Center is the only hospital that offers inpatient beds for children who need mental health treatment. The hospital offers 26 total behavioral health residential, inpatient and crises beds, but only two are children’s beds, according to a presentation from the town hall.

“We have to do a lot better on that, so two beds in the county for children,” Olson said.

Some also shared personal stories about navigating the county’s mental health resources and national resources.

Rhonda Wells-Wilbon, a licensed clinical psychotherapist, said she’s struggled to access resources for her 24-year-old daughter who has a mental health disorder.

[Prince George’s County to mandate security cameras in some housing facilities]

“As a mother whose daughter is 24 years old suffering from mental health, every time I call the crisis response line, 988, I got no staff and I never got connected to any services,” Wells-Wilbon said.

Since the 988 suicide and crisis lifeline — a national call line staffed largely through state and local call centers — was launched in summer 2022, several callers have reported long wait times and other challenges.

Wells-Wilbon urged the county health department to offer more resources and support programs to people with mental health disorders as well as their caregivers and family members.

Others, like resident Bill Barnes, said knowledge of county-offered resources isn’t widespread.

Barnes said he has spent 42 years in the Prince George’s County school system in multiple roles, but was not aware of the mental health resources available to him and his family members until his granddaughter needed them, he said.

“I had no clue what these services were,” Barnes said. “It wasn’t until we were in this situation and found out that we need help.”

In response to residents’ testimonials, Blegay requested that Levy and others from the health department provide resources to individuals and meet with them to further discuss their concerns.

District 5 council member Jolene Ivey underscored the importance of residents reaching out to one another for support during the ongoing mental health crisis.

“There are a lot of mental health issues but many of them have their roots in loneliness, and we should all make sure we all reach out to each other to our neighbors,” Ivey said.