The University of Maryland’s Native and Indigenous Student Union hosted a fundraiser on Friday to remember Native and Indigenous children who were separated from their families and sent to residential schools in the United States and Canada.

The fundraiser, in front of McKeldin Library, recognized Canada’s National Day of Truth and Reconciliation on Sept. 30 — also known as Orange Shirt Day — where people wear orange shirts to spread awareness about residential schools.

Starting in the late 19th century, Native and Indigenous children were sent to government and Christian missionary boarding schools meant to erase their culture and assimilate them into American civilization, according to the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

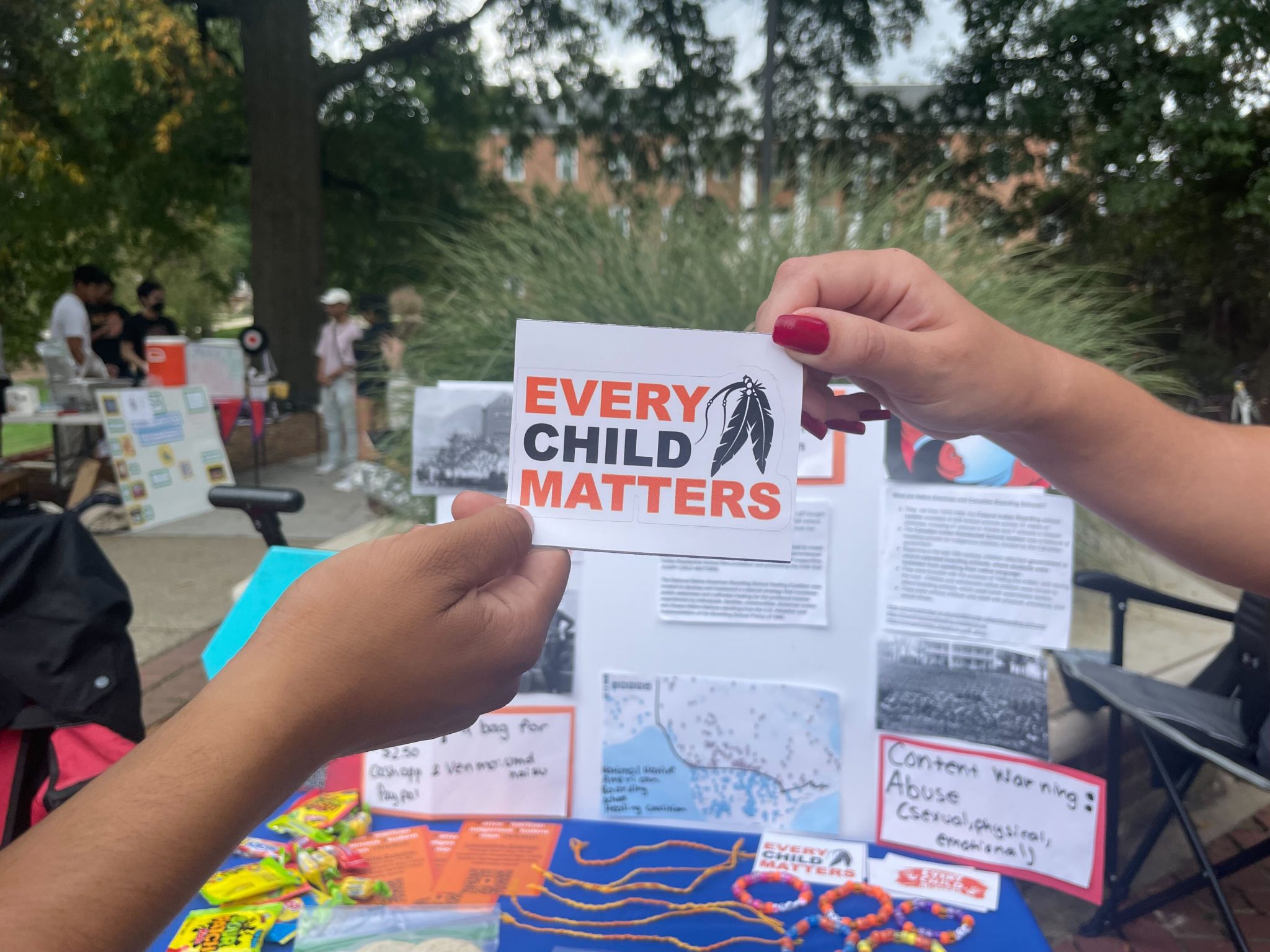

To bring awareness to these schools, NAISU sold cookies, orange bracelets and stickers with the message “Every Child Matters,” along with displaying a board detailing the history of residential schools.

[New diversity and inclusion assistant vice president emphasizes importance of student voice]

A percent of the group’s proceeds will be donated to the National Native American Board Healing School Coalition, according to senior elementary and middle special education major Paulina Martinez, the president of NAISU. The coalition advocates for and provides resources to Native and Indigenous people impacted by residential schools.

Martinez said people are often unaware of the legacy of residential schools because they are rarely covered in the media and in educational curricula.

“We just want to bring awareness to it because every child matters,” senior English major and NAISU vice president Vy Thompson said. “That’s collectively what we want to agree on, that the residential schools were wrong and they were damaging and it was traumatic. These children should have never had to go through that.”

The idea to wear orange shirts came after six-year-old Phyllis Webstad was stripped of her own orange shirt upon arriving at a boarding school in 1973. She was one of tens of thousands of children who were sent to schools through which the government aimed to “kill the Indian, save the man,” according to the coalition.

“They were sent to these schools and a lot of them never saw their families again, never saw their tribes again,” Thompson said. “A lot of them didn’t make it out of the schools because [of] abuse, neglect, tuberculosis, disease.”

Thompson said there are still unmarked graves of children who did not survive residential schools. Some Native and Indigenous children were also forced into assimilation after being adopted into non-Indigenous families, she added, leaving some individuals still attempting to reconnect with their tribes.

Bayley Marquez, an assistant American studies professor at this university, said although federal funding for residential schools ended around the 1960s, some of these schools still serve Native and Indigenous students. Some schools have transitioned to supporting Indigenous life, but others are still tied to systems of education that are inconsiderate of Indigenous issues, she said.

[UMD Latinx student group hosts US Census Bureau director]

“Our education system has shifted a lot from ‘kill the Indian, save the man,’ but it still has a lot of problems in how it represents Indigenous people,” Marquez said.

The legacy of residential schools still affects people today because there is a sense of distrust of educational institutions in some communities, Marquez said.

For Martinez, this is evident through generational trauma in families where older relatives once endured residential schools.

“A lot of people don’t know how long the system existed, but it still affects Indigenous communities today.” Martinez said. “There’s a lot of generational trauma and a lot of kids had grandparents who went to residential schools. So you know… a lot of healing that still needs to be done.”