Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

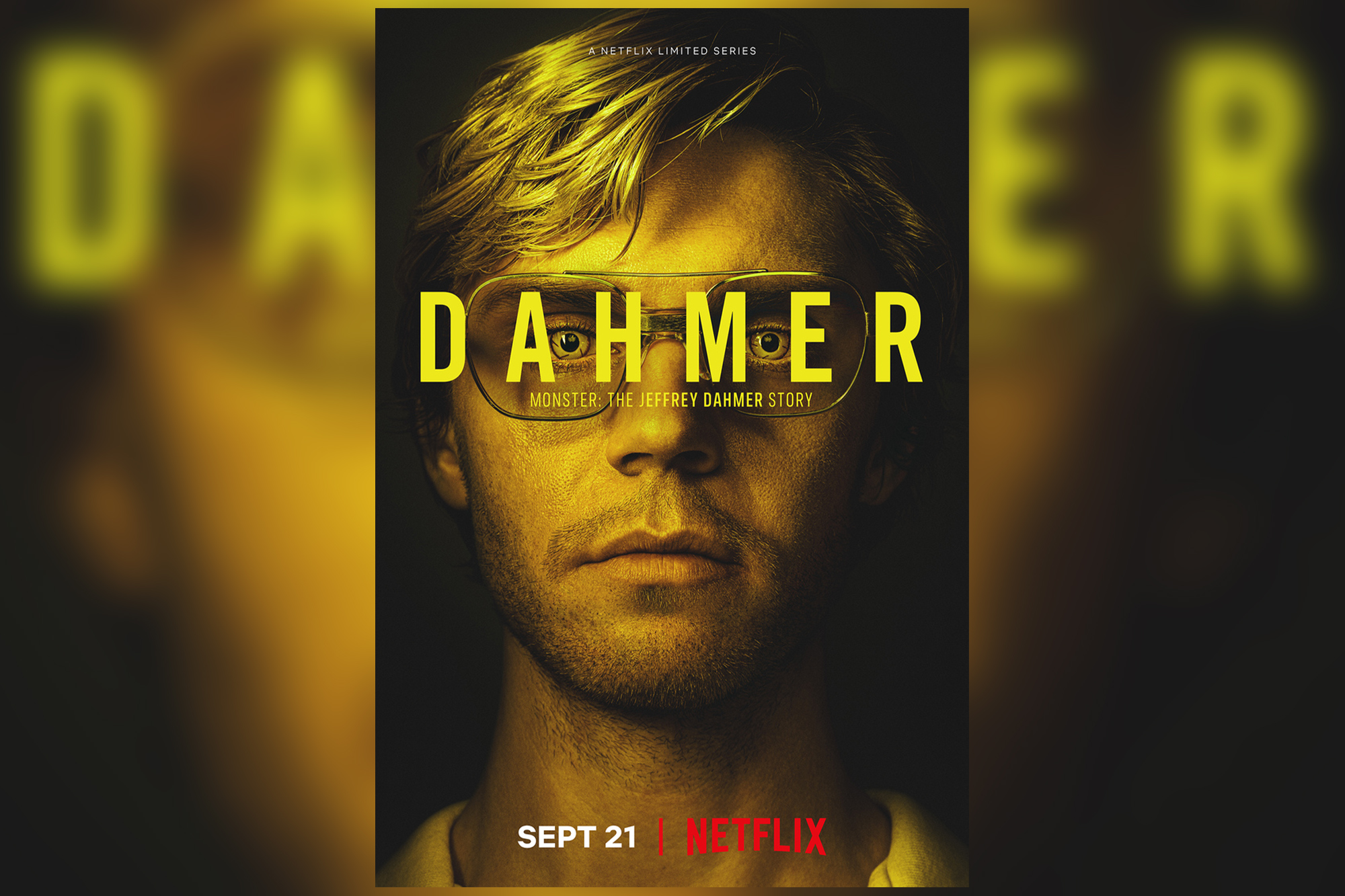

The television show DAHMER – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, has garnered significant media attention after it premiered on Netflix last month. Centered around famous serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, who mostly targeted young men, the show became one of Netflix’s most-watched series of all time.

On the surface, Netflix’s promotion of the show has been strange. To advertise the show, Netflix tweeted a scene in which one of Dahmer’s victims escaped before police brought them back into Dahmer’s apartment, saying it was a scene the streaming service “can’t stop thinking about.” The scene was based on the harrowing murder of Konerak Sinthasomphone, a fourteen-year-old victim of Dahmer’s.

But there are further details that make Netflix’s handling of the show problematic: The company or the creators did not speak to Errol Lindsey’s family about the show premiering. Lindsey was one of Dahmer’s victims. Instead, Eric Perry, one of Lindsey’s relatives, tweeted that he found the series “retraumatizing” and his family was “pissed.”

Movies and television shows like these — slightly fictionalized depictions of real events — continue to prove popular among audiences. But when you’re dealing with real events, you’re dealing with real people. If creators want to ethically make a movie or television show, they must take the necessary steps to reach out to those who lived through the reality of the fictional story they want to tell.

Rita Isbell, the sister of Lindsey, said she didn’t feel the need to watch the show made about her brother’s killer because she lived through it. “It’s sad that they’re just making money off of this tragedy. That’s just greed,” Isbell told Today.

This never had to happen. The solution to this problem is so simple it compounds the frustration around the issue as a whole: All creators have to do is reach out to the family for commentary. Not only might asking for their opinion or experiences surrounding the topic ease their pain at having to watch a reenactment of their loved one’s death, but it has the potential to add more to the piece. It can add nuance, context and truth that may not be available without directly seeking firsthand accounts from people who lived it.

At the very least, production companies should be reaching out to families to tell them the show is going to be made so they don’t wake up to a horrifying shock.

This problem isn’t just present in DAHMER. Lifetime just released a film titled The Gabby Petito Story, about Petito’s murder that occurred just last year despite explicit disapproval from Petito’s family. It’s baffling a network feels it has the right to tell the story of a woman’s murder trumps that of her own family.

This conversation certainly points to a larger issue surrounding true crime as a whole. Is it ever right to consume someone’s death or trauma for entertainment? The concept, on its face, certainly feels wrong.

But it depends on the consumer and it depends on the creator. Some fictionalizations of real-world events focus far too much on the person who committed the wrongdoings. DAHMER mentions the killer’s name not just once, but twice in its full title and fails to highlight undiscussed aspects of the murders that would warrant making the show at all. Instead, the true crime-focused media can and should embrace the opportunity to shed light on the lives of the victims with the help of the victims’ families.

There are ways for this to be done right. Dopesick is a series on Hulu that delves into the opioid epidemic, the horrors of addiction and the heartless marketing of pharmaceutical companies for drugs that have killed hundreds of thousands of people. For a story so deeply personal, the makers of the show rightfully found it important to consult people who were suffering from addiction to make their show more realistic.

DAHMER had the opportunity to take the narrative often told about serial killers and refocus it on those whose lives have been impacted. With the help of the victims’ loved ones, the show could have highlighted Dahmer’s victims instead of Dahmer himself and who they were outside of their deaths. It could have helped viewers grasp why these deaths were so tragic, instead of painting them as a spectacle.

The personal nature of the show is what makes it so powerful — a factor that should undoubtedly be in all stories based on true crime — and a factor which can only be achieved if the victims’ families give their approval and their insight.

Rebecca Scherr is a junior English and government and politics major. She can be reached at rsscherr101@gmail.com.