The Black and natural hair communities carry a long, painful history of battling with Eurocentric beauty standards.

“[Throughout segregation] we were also being demeaned for the things that we are, whether it’s our facial features, our hair, stuff like that,” sophomore psychology major Nana Buachie said.

Africans have been doing elaborate hairstyles with cloth, beads and shells since the 15th century, wrote awarded educator and scholar of fashion design Dr. Tameka Ellington in a paper titled “Natural Hair.”

“In West Africa, hairstyles could indicate a person’s marital status, religion, age, ethnic identity, wealth, and position or rank within the community,” Ellington wrote in the article.

The different ways slaveholders used enslaved people’s hair against them is part of how hair, especially natural, textured hair, has been politicized, said Dr. Jason Nichols, a lecturer in the African American studies department at the University of Maryland.

Black women were forced to cover their hair or cut all of their hair off to make them “less attractive” to Europeans and avoid relationships between slaveholders and enslaved people, Nichols said. This did not prevent sexual assaults or relationships.

Slaveholders would also compare the soft, fluffy nature of natural, textured hair to the coat of animals, intending to justify ownership and abuses, Ellington wrote in the article.

“Part of white supremacy and what was done to enslave people was to dehumanize them and make them think that white is right in terms of a standard of beauty,” said Nichols.

He said this increased after emancipation, in an attempt to create a “grotesque” and violent stereotype as a form of racism against Black people.

“In addition to making Black people seem as though they are violent … [there were] images in the media that justified trying to control Black bodies,” he said. “Hair was a big part of that.”

There was pressure placed on Black people and other groups, such as Indigenous people, to emulate white beauty, Nichols said.

“So we’ve seen throughout history Black people put themselves through really painful processes, in order to make their hair seem closer to whatever the white standard is,” he said.

Madam C.J. Walker, the first Black female, self-made millionaire in the U.S., sold hair products that catered to Black women and helped them grow their hair in the early 1900s.

From the 1920s to the 1960s, Black men would straighten their hair into the “conk” style using relaxers. Musician Chuck Berry and civil rights activist Malcolm X — before his religious conversion — were among them.

The process involved applying a product that contained the chemical lye, which can be found in drain-cleaning products, Nichols said. The risks of getting a conk included burning your scalp, never growing hair again or even damaging your eyes if the lye got in them.

A push against the years of hair discrimination occurred during the civil rights movements and Black power movements, when Black people, including musician Jimi Hendrix, wore their afros and other natural hairstyles to represent “cultural freedom and nonconformity,” Ellington wrote in the article.

It definitely can be a political statement to wear hair as it naturally grows out of one’s head, said Nichols.

“It might not be for other groups of people,” he said. “But for Black people, because there has been such an assault on our aesthetics … to wear your hair naturally was a statement that said, ‘I’m Black, I’m proud.’”

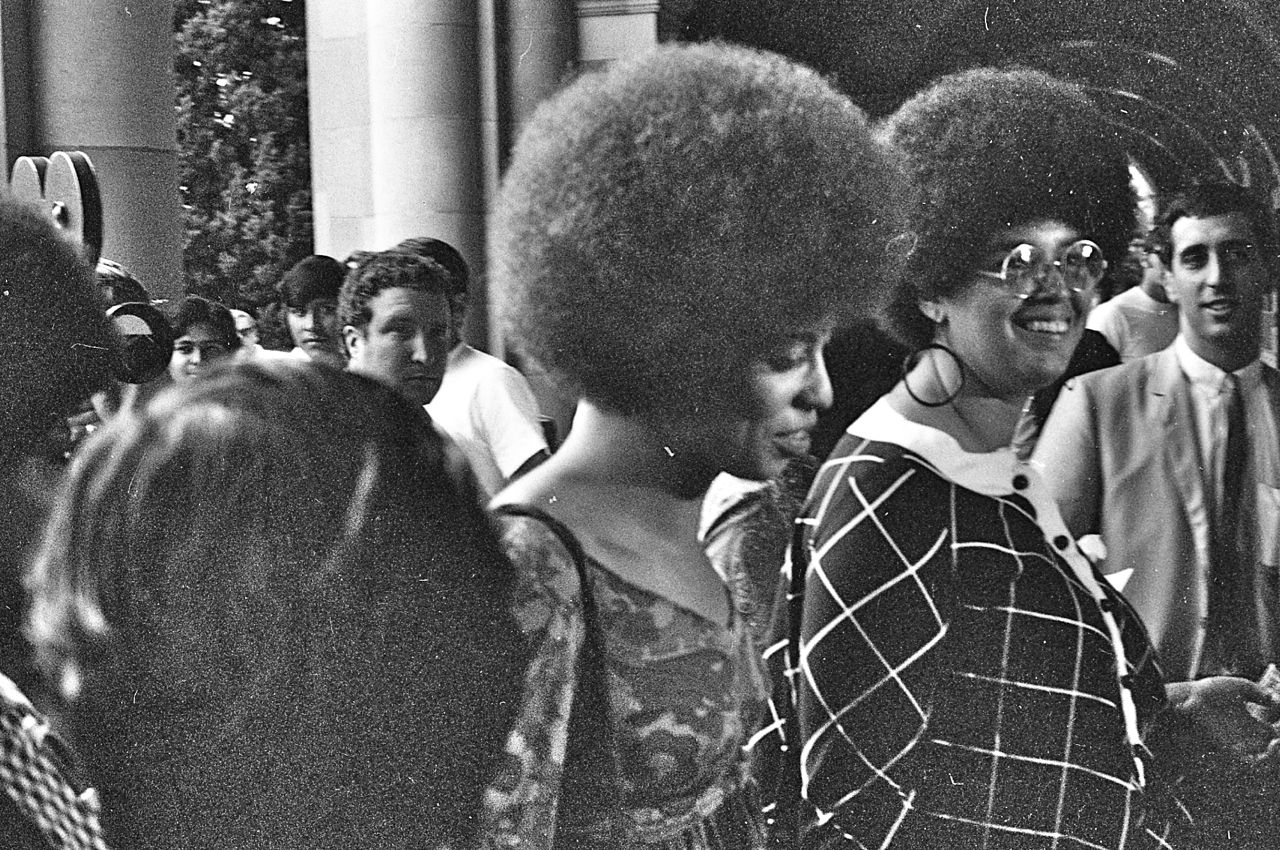

Activist Angela Davis was known for making a statement with her natural afro.

Davis, an important figure in the civil rights and Black liberation movements, was put on trial for her alleged involvement in a politically-charged murder connected to members of the Black Panther Party but was acquitted.

Nichols sometimes feels bad that people focus more on her hair than her contributions, but said that she is still an important hair icon through the impactful image of her going into the courtroom and throwing up the Black power salute with her lustrous afro. This courtroom moment was an inspirational moment for Black people.

“Even though she’s on trial for her life, she’s so free,” he said. “She’s politically free, she’s mentally free and you can see with her hair, she’s physically free from the chains of white supremacy.”

In the D.C.-Maryland-Virginia region, another historical moment came years before in the 1960s, when Robin Gregory was the first homecoming queen to sport an afro at Howard University.

“The audience saw her silhouette, and they saw the outline of her afro while all the other women had kind of accepted that you had to have your hair pressed in order to win this beauty pageant,” Nichols said. “But she kept her afro and the crowd just exploded.”

Nichols explained that white supremacy adjusts to these cultural changes and presents itself in different forms, with different hair relaxing styles surging.

The Jheri curl became popular in the 1980s and 1990s when those with tight curl patterns would use chemicals to loosen their coils.

“Maybe it didn’t look like a white person’s hair, but it looked in a way that was closer to a white standard,” he said.

The style worn by Michael Jackson and rappers Ice Cube and Eazy-E took off in Afro-Latino and Black communities and is currently making a comeback for those with natural hair to adopt styles such as the Jheri curl and waves without chemicals.

Nichols said it’s important to note these chemical changes in hair aren’t always necessarily to fulfill a white standard of beauty. He grew up in Baltimore where women would do hairstyles involving finger waves, glitter and perms to meet the Baltimore standard of beauty.

Nichols has recently started to notice some Black women say, “I am not my hair. Stop obsessing about my hair because I’ve stopped obsessing about my hair.”

Protections for people with natural hair to freely decide how they want to wear their hair is a step forward, said Nichols. One of these is the Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair Act, known as the CROWN Act, which prohibits hair discrimination in the workplace, it was passed in Maryland in 2020.

Nichols remembers when he graduated college during the 2000s and guys around him were talking about it being time for them to cut their locs to get a job.

Now he sees young Black people wearing their hair how they want to rather than conforming to society’s standards of beauty.

“It’s so freeing, and I’m loving what I’m seeing,” he said.