Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

When students enroll at the University of Maryland, we sit through a training on sexual assault prevention. I remember clicking through the videos, listening to the narrator discuss the importance of consent. That’s something we’ve been taught since health class in middle school: consent is key, consent is important and sexual assault is wrong. I’ve met very few people who disagree with those statements.

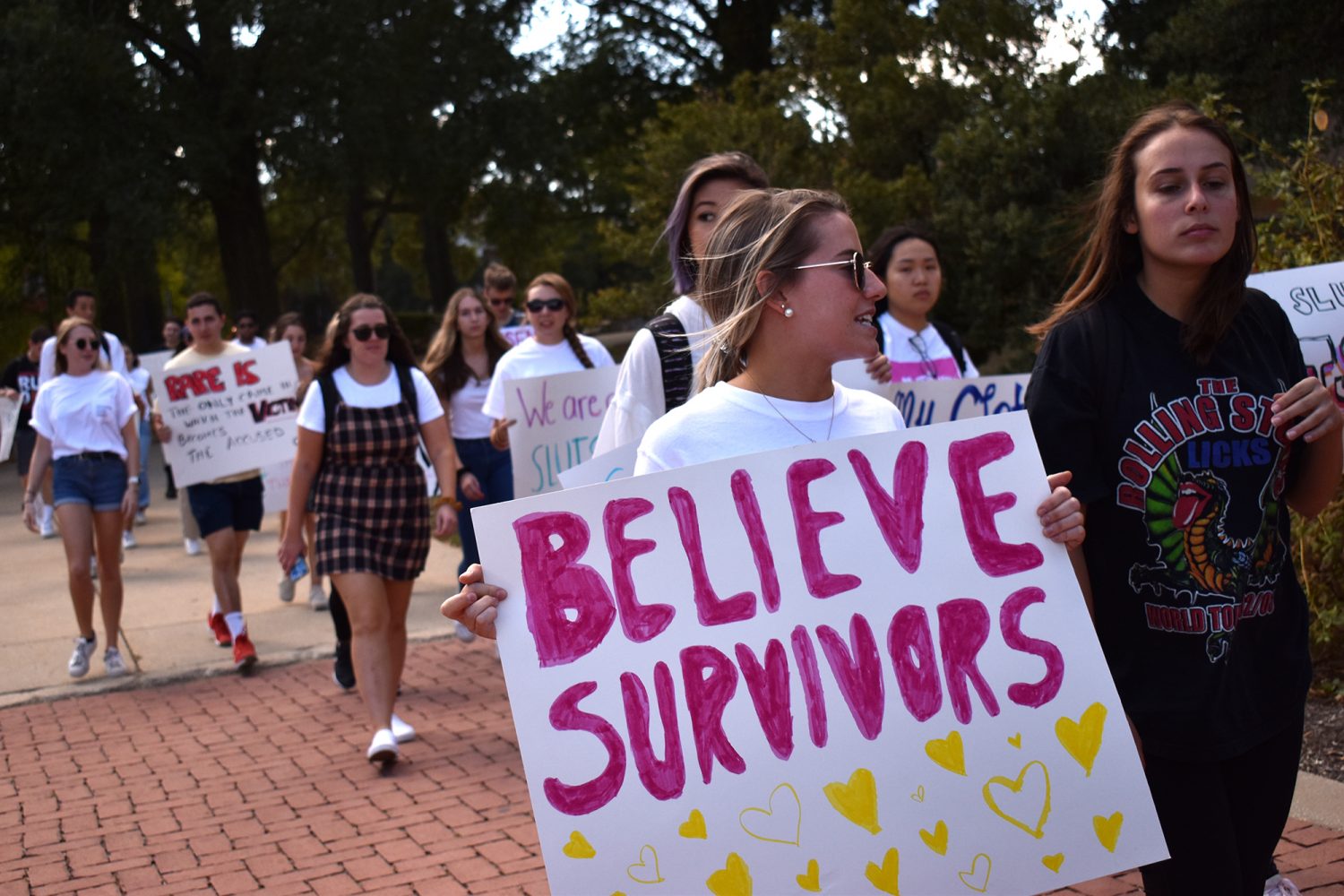

So, if we’re all in agreement that consent is good and sexual assault is bad, why does it take so long for survivors to be believed — if they are believed at all? To help campus members believe survivors and hold assailants accountable, the university must implement better training for students on why cases of sexual assault are not as clear-cut or simple as other cases.

I remember when Christine Blasey Ford testified in chilling detail as to how she claims Brett Kavanaugh assaulted her during his nomination to the Supreme Court in 2018. I remember the doubt from others who gruffly asserted it was all a political scheme to stop Kavanaugh’s nomination, that it made no sense that Ford just so happened to recall this after decades, that there was no way the Catholic father of two could have done such a thing.

I remember the testimony of Olympic athletes from earlier this month, relaying the horrific abuse they suffered under Larry Nassar, a man who was supposed to be caring for their health. Though Nassar is currently serving an effective life sentence in prison for his crimes, complaints of his misconduct were ignored for decades.

While they emerged in 1997, Nassar was not convicted for the abuse of many gymnasts until 2018. When interviewed by the FBI about Nassar in 2015, athlete McKayla Maroney relayed her traumas in detail to the agent. She was met only with silence.

And the case at the forefront of my mind is allegations of sexual assault against the University of Maryland’s chapter of the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity — allegations that feel anything but new.

There’s a continued lack of belief in sexual assault survivors because institutions are failing to adequately educate their communities on the reality of sexual assault and its psychological impact, which makes it easy for some to use misinformation to dismiss claims of sexual assault.

Take this university’s sexual assault prevention training. Not only is the course online, making it easier for students to skim through it and ignore half the information being shown to them, but it focuses more on the importance of consent and caring for survivors of sexual assault after the fact. Both are certainly important, but survivors don’t just want sympathy — they want to be believed, and they want justice.

Presenting the issue to students and staff in a simplistic, forcibly uncontroversial fashion only erases the nuanced approach sexual assault requires. It hinders the ability for survivors not only to be believed but to have their allegations taken seriously and treated with care by the university. It allows too many people to turn a blind eye, to mourn the tragedy rather than doing something to actually solve the problem.

Survivors often aren’t believed because they don’t produce enough “evidence.” This evidence can often only be collected right after the assault has occurred, which is extremely difficult after such a traumatic experience.

Additionally, there’s unjustified hysteria over false sexual assault allegations. Studies show only between two and seven percent of sexual assault allegations are false, and yet countless of women don’t report out of fear of not being believed. The same people demanding documented evidence and timely confessions to believe survivors are the ones inadvertently shutting them down and perpetuating rape culture.

If the university and other institutions presented this information in a more engaging and meaningful way to its students and employees, perhaps we wouldn’t still have to explain this when survivors bravely come forward. Perhaps the university itself would do a better job at condemning sexual assault and reprimanding the assailant as soon as possible. It’s impossible to combat such a nuanced and complex issue with simple, cut-and-dry PowerPoint slides.

And it’s impossible for any of us who haven’t been sexually assaulted to ever understand what survivors go through. But if institutions adequately train students and employees on the psychology behind sexual assault instead of ignoring the complex examination the issue demands, that education can help make our communities safer and more supportive.

Rebecca Scherr is a sophomore government and politics and english double major. She can be reached at rsscherr101@gmail.com.