Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

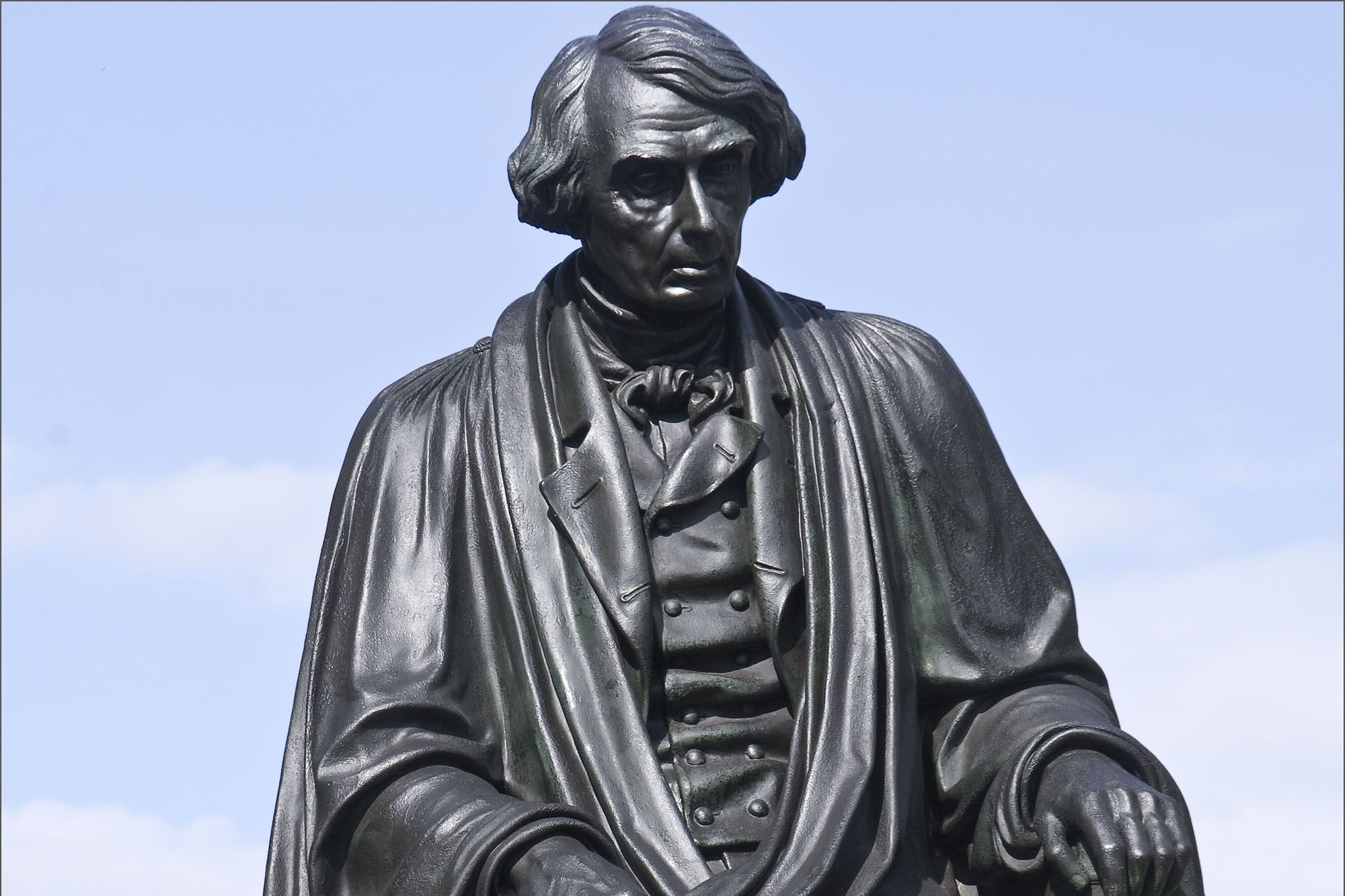

After more than 130 years, the statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia, is finally being removed. It’s understandably become one of the biggest news stories of the last few weeks — removing one of the most notable monuments to the Confederacy from its former capital is a significant step toward dismantling the rosy way too many people view the racist Confederate Army.

However, no matter how important it may be, removing Confederate monuments is still a symbolic gesture. Decisions like these should be viewed for what they are: necessary first steps in confronting racial inequality that must be followed by more direct, radical actions that adequately address the oppression people of color face today.

Let’s take a look at one issue disproportionately affecting people of color: poverty. Black and Hispanic Americans are more than twice as likely to live in poverty as white Americans. This is not an accident — it is the intended result of centuries of white supremacy.

Expansive and fully funded anti-poverty programs could help mitigate this. These social safety net programs provide benefits, including food assistance, health care, shelter and tax credits to people who often could not get by without them, and they could help even more people if they were adequately expanded.

These are programs that have been shown to reduce poverty and boost pathways to economic mobility and serve a significant number of people of color. For example, a majority of people who receive Medicaid benefits identify as non-white. Expanding these benefits would improve the prospects of millions of people of color, yet when this policy option gets brought up, it’s not very easy to get it enacted.

Lawmakers, especially those who oppose these programs, rarely bring up racial inequality and the social safety net in the same context. However, any serious look at either issue will show that they are connected.

The effects of racism have always been tied to economics — racial inequality cannot be comprehended if economic status does not play into it. Not funding these anti-poverty programs feeds the white supremacy which created these inequalities to begin with.

This larger context gets lost in most debates about racial inequality. It is easy to stand up to the most overt, obvious racism in symbolic ways, but it is harder to address the complex economic effects systemic racial inequality yields. The decision becomes easier when there are no prospects of economic mobility to be considered.

This is why the proposal to make Juneteenth a national holiday passed easily, but proposals to expand social safety nets have been in congressional limbo. These are programs that could actually lead to increased economic power and thus increased political power for people of color, which is a threat to the current power structure.

But even things that should be easy decisions, such as removing Confederate monuments, have become a subject of debate. When the simple decisions are fought tooth-and-nail, there is no oxygen left to discuss more complex solutions. The no-brainer decision becomes the great achievement that leaders can pat themselves on the back for without doing anything to address the terrible economic situation so many people of color find themselves in.

Removing the Confederate statues is a necessary and overdue decision, but it has dominated way too much of our national conversation. We need to stop debating what should be easy decisions and move on to considering more consequential solutions to racial and economic inequality. Our social safety net is a key part of that equation. Expanding it will create more opportunities for people of color who have been kept in poverty for too long.

Adam Cullen is a junior government and politics major. He can be reached at acullen@umd.edu.