Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

This year has been pretty rough on my faith in humanity. Our leaders can’t seem to figure out how to work together on fighting the pandemic and there seem to be so many geopolitical spats threatening to boil over.

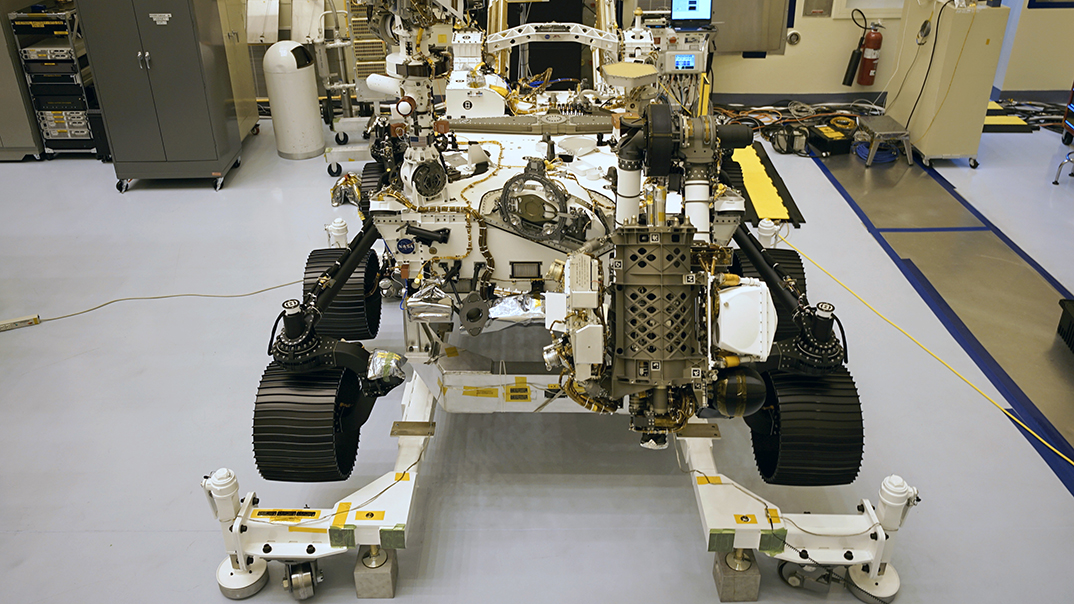

But no matter what, the scientific community remains seemingly insulated from the regular political conflicts of the world. This feels especially true with modern space exploration. Any enterprise that gathers information from beyond our little ball of water and rocks is a huge societal advancement for everyone on the planet. Unfortunately, NASA’s latest project to land people on the moon — adorably named the Artemis program — has already run into political and policy problems.

After NASA awarded SpaceX, a private space exploration company, a $2.89 billion contract to help land the next group of Americans on the moon, the two other companies that were passed over for this contract are protesting NASA’s decision with the Government Accountability Office. As a result, the contract was suspended, and the project is inevitably going to be delayed.

This shatters the shallow illusion that STEM is isolated from politics and policy. Every scientific endeavor, from climate change to COVID-19 relief, is controlled by politics. Government affairs have a huge impact on what scientists and engineers can do. It’s easy to forget that regulation, trade and protests control what resources are accessible.

People who work in STEM need to be more involved with these bureaucratic and political decisions. It can be frustrating for the scientists and engineers to see their lives’ work mired in red tape, caught up in confusing political deadlock or, worst of all, completely misunderstood. There must be a change in the way both STEM and civics are taught, with an increased emphasis on how the two are intertwined.

I can’t help but think of the infamous Senate hearings from 2018 when legislators struggled to understand basic technological concepts, such as smartphones. Of course, behind the scenes, there are tons of people who actually do know what they’re talking about. There are agencies full of scientists and engineers, such as NASA, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institute of Standards and Technology and other agencies who work with policymakers on topics as varied as climate change and nuclear disarmament.

But these scientists aren’t the decision-makers.

The majority of the scientific community is not invested in government affairs at all. As a government and politics and mechanical engineering major, whenever I introduce my majors to other people, I typically get questions about how they’re related. Just as nearly every STEM field is math in disguise, politics is the puppeteer behind most large STEM projects. They’re not really two separate subjects, they’re just different sides of trying to understand and improve society.

However, the disconnect between STEM and politics is solvable. Current STEM students need to learn how to communicate with regulators and others who decide which projects proceed. We shouldn’t have to watch an important project like the Artemis program stall due to bureaucratic reasons instead of scientific ones. In other words, it’s not enough to just know how to make things work; us STEM folks need to be included in the political decisions that decide our research and projects.

There are actually two parts to this problem. First, civics education, in general, is lacking. I mean, were you even required to take a government class in high school? And at this university, students who aren’t majoring in a topic related to government or public policy don’t need to take courses in these subjects either.

Additionally, STEM students don’t have many incentives to continue to pay attention after the civics course is over because the content doesn’t immediately seem relevant. I’ve seen too many STEM students who can happily spend hours on physics or math problem sets but then immediately shut down when a policy issue is brought up.

Of course, I’ve seen the opposite with government students, too. The crucial difference here is while we don’t all need to understand calculus, we do need to understand the basics of how our government works. For an institution that controls so much about scientific advances, it’s problematic that STEM students are generally politically uneducated.

The big problem is getting people who really don’t care about the policy side of science to take an interest. Part of the solution has to start early, with more civics course standards for everyone in middle and high schools, before people decide whether they’re going into STEM. Here, it could be as simple as mandating that one of the DSHS general education requirements at this university is a government or public policy course.

Within the STEM community, we need to foster a culture of interdisciplinarity instead of specialization. Instead of treating government affairs as an unrelated topic, we need to think of it as an extension of the problem-solving and analytical skills we prioritize. Just as we emphasize project management and teamwork beyond the simple science, we need to treat communicating with the groups that decide the fate of our projects as essential.

Really, STEM people and government people don’t occupy separate worlds. Everything is part of the political world, especially STEM, and the sooner scientists and engineers have more decision-making power over how society-advancing projects proceed, the better off everyone will be. The only way to do this is for education to become more interdisciplinary.

Jessica Ye is a freshman government and politics and mechanical engineering major. She can be reached at jye1@terpmail.umd.edu.