POV: It’s 2014. You just got home from school and you’re feeling more frustrated than ever. Your language arts teacher told you ending your fiction story with “it was a dream” is not a strong (or good) ending. You decide to go on YouTube, and you see a new video titled “The ‘Boyfriend’ Tag (ft. Troye Sivan) | Tyler Oakley.” All is good.

Since those good old days, YouTube content has seen a massive cultural shift, and it’s seen an even bigger shift from the platform’s inception in 2005. Nowadays, it seems you can’t log onto the website without seeing a new apology video. But YouTube content wasn’t always like that.

Something that has always been a part of YouTube was the drama. I have been an avid YouTube viewer since 2013, and I’ve seen a lot of creators rise and fall from grace. I’ve seen lots of drama come up and guiltily watch drama recap channels so I can stay up to date with it. I’ve recently noticed the word “drama” is used too loosely, minimizing the issues at hand.

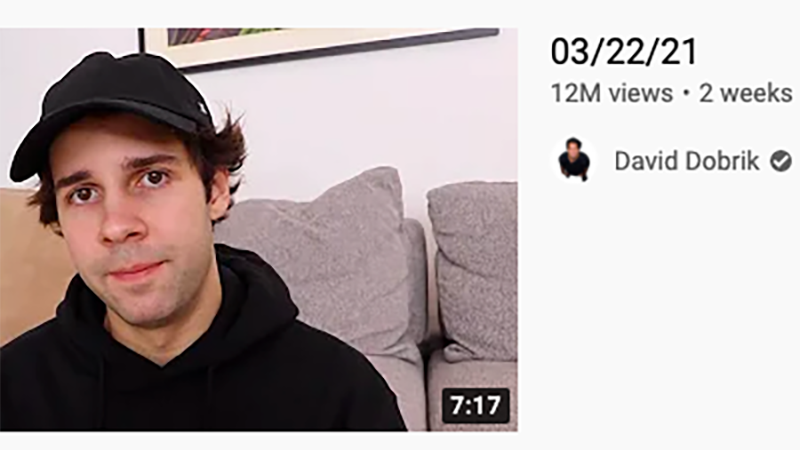

It does not sit right with me that recent situations — including accusations that James Charles exchanged explicit photos with a minor and allegations that David Dobrik facilitated a situation where a young woman was sexually assaulted — have been referred to as “drama.”

[Celebrate spring at these College Park outdoor dining spots]

In 2013, YouTube drama was actual drama, not genuinely criminal and heinous acts. I remember when rumors started to circulate about JennXPenn and Andrea Russett falling out or when Connor Franta left O2L — that was what we considered drama.

Yes, there were instances of YouTubers of 2013 doing inappropriate things, like when Sam Pepper did his infamous butt-grabbing prank. But back then, those incidents were infrequent, and the creators were mercilessly held accountable. It now feels like these instances of criminal acts of “drama” are on a monthly basis.

By referring to these instances as drama, you minimize what is actually happening. By saying allegations that James Charles is talking to minors in a predatory way is just “drama,” you minimize the experience those people went through. To an outsider it’s just “drama,” but you forget actual people went through this; it wasn’t just a piece of content to consume, it was a real-life event.

When reflecting on this change in drama, you look at the content coming out during this original YouTube era and it’s starkly different than content made now. A lot of the videos made were different Pinterest or Tumblr challenges like “The Boyfriend Tag” or “Name that Tune.”

I would look at my recommended tab and could watch Grace Helbig do the bean-boozled challenge, then Joey Graceffa do it, then Ricky Dillon, then Amanda Steele — and still not get bored. I was falling in love with the person, not the content. It was so structured there was nothing you could really do wrong.

And that’s also partially why big hitters at the time like Shane Dawson or Jenna Marbles were so successful. They were creators who made unique content where they, quite frankly, made a lot of poor taste jokes that people ignored. And it wasn’t mostly until this past year both Dawson and Marbles were held accountable for their actions.

One creator who ushered in this new, more unique, era of YouTube with somewhat controversial content was Tana Mongeau. Her infamous “I GOT BANGED WITH A TOOTHBRUSH: STORYTIME,” stands out; I remember that video being hot gossip among YouTube fans. Her content was bold and raunchy and people ate it up as much as they were disgusted by it.

[The RealReal’s upcycled collection reimagines luxury sustainability]

As time went on, more and more creators kept trying to create more new and unique content to get a rise out of people. As opposed to falling in love with the person, you were falling in love with the content — and that’s where things went wrong.

This shift created a culture where creators felt the need to push boundaries. It got to the point where creators (ahem, David Dobrik) would coerce their fans to do things for them. Whether it was providing content for them, or even self-gratification, people felt the need to serve their favorite content creator.

This new era of content has created a toxic environment between fans and creators, in which people look for every wrong step the creator makes to call it drama — but then ignore the genuinely bad things they do because it’s just seen as minute drama.

I think the saying “if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck” is relevant to this situation. If it’s drama, then call it drama. But if it’s something with genuine trauma and serious consequences, then address it as such.