Content warning: This article discusses anti-Asian violence and racism.

As the rain drizzled Wednesday evening, Tiffanie Choi stared into the crowd in front of her by the steps of McKeldin Library at the University of Maryland.

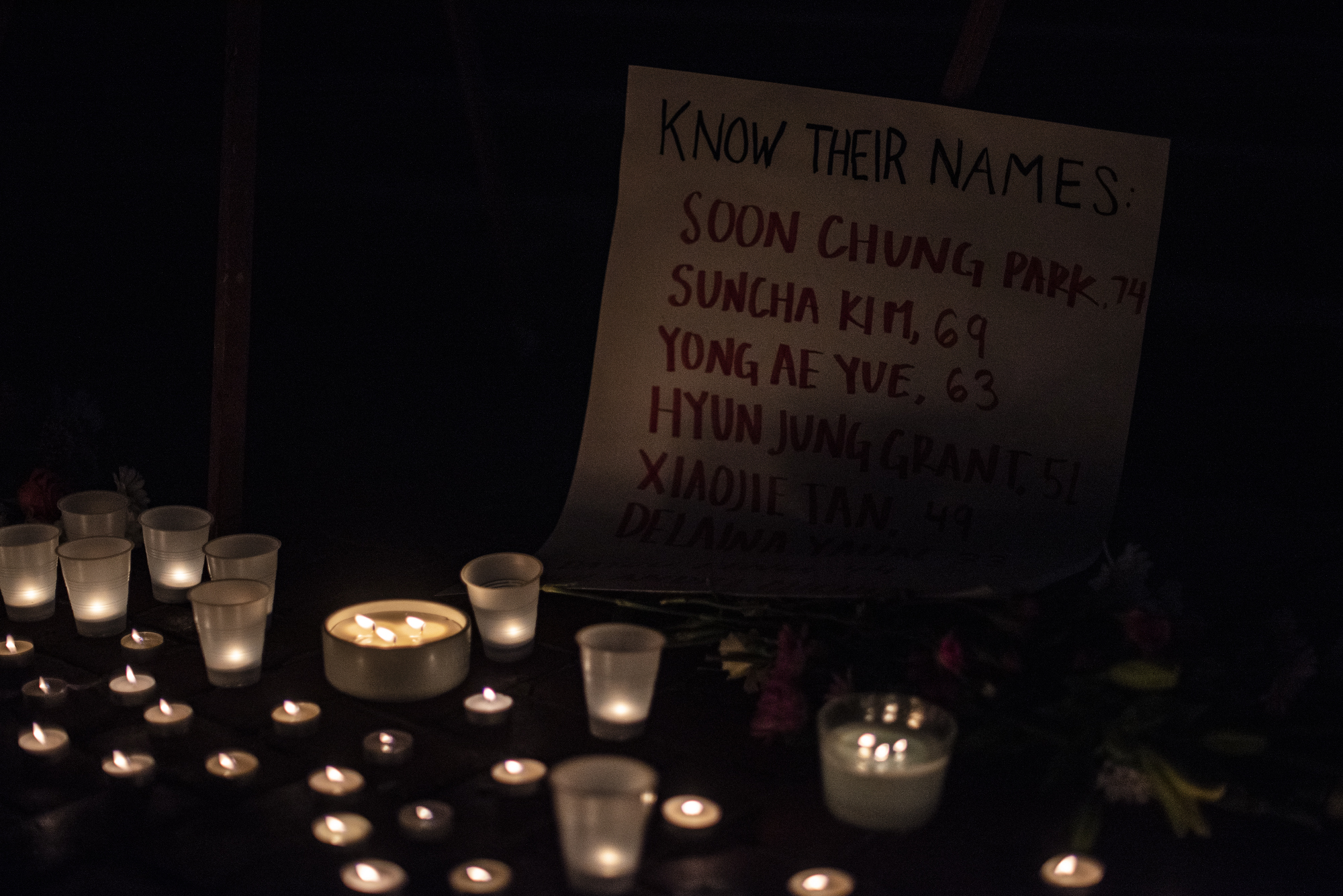

In front of her were large portraits of the eight people who were gunned down at three spas in Atlanta on March 16 — six of whom were Asian women. Many of them reminded Choi of her own mother, she said. She felt lost, as the eyes of about 100 people stared back at her. Heartbroken.

Eight beautiful lives were taken away too soon, she said. She said their names.

Soon Chung Park.

Hyun Jung Kim.

Suncha Kim.

Yong Ae Yue.

Xiaojie Tan.

Daoyou Feng.

Delaina Ashley Yaun.

Paul Andre Michels.

“Do you know what I do on my bad days? What we do on our bad days?” Choi raised her voice. “We mourn. We cry.”

Three sophomores at this university — Elizabeth Hsu, Lily Larson and Choi — organized a vigil Wednesday evening to remember and honor the lives lost and to stand against anti-Asian racism.

For two hours, as the sky gradually grew darker, a series of speakers grieved and called for action, some sharing poetry and quotes from social justice activists. Many shared the frustration that comes with being a person of Asian descent living in a country with a history of anti-Asian hate and discriminatory policies — and having their concerns of racism and hate continually dismissed.

[Asian Americans at UMD grapple with surge in violence against their community]

University President Darryll Pines also spoke at the event, offering solidarity to the Asian and Asian-American communities.

Jackie Liu, one of the speakers and the co-president of the Asian American Student Union at this university, told the crowd they wished they could say they were shocked when they heard the news of the attack. In reality, she was disappointed, frustrated and angry, the biology and women’s studies major said. For the past year, Liu — and the nation — has witnessed a rise in anti-Asian violence.

Right now, people of Asian descent are afraid to live and to walk out their homes, Choi said. There is no system that protects them, the computer science major said.

When someone in one of the Atlanta spas called 911, the caller had to “beg” the police to save their lives, beyond scared, as they hid from the shooter, Choi said. The dispatcher had trouble understanding their English, Choi said, her voice heavy with grief and anger.

This resonated with Choi. The daughter of Malaysian immigrants, Choi grew up watching people bully and harass her mother for speaking English with an accent. They couldn’t understand her, Choi said. She wanted to say something, but she was scared.

“I’m so sorry that I didn’t speak up then,” Choi said. Her voice broke, then rose stronger. “But I promise now to always speak up for you … when you need my help, I’ll be there. When they need help, we will all be there. We will be there for our entire community because we have to support each other.”

The vigil was meant to honor the victims of last week’s attack — and all of those who suffered from violence and hate crimes spurred by anti-Asian hate — and Choi urged attendees to remember them.

“They are more than just eight victims and more than just eight names,” Choi said. “They all have their own stories.”

Choi went on to share those stories.

Daoyou Feng, who was 44, had just started working at the parlor. Friends described Feng as quiet and kind.

Hyun Jung Grant, 51, whose maiden name is Kim, worked long hours to support her sons through college. She had a young spirit and was close with her sons. She loved to watch Korean dramas.

Suncha Kim, 69, emigrated from Seoul, South Korea. Like many others, she wanted to provide a better life for her family, her family said. Her family described her as a pure-hearted person who everybody loved.

Paul Andre Michels, 54, grew up in southwest Detroit. One of nine siblings, he was nice, hardworking and loving, his brother John said, and dedicated to his wife and family.

[Pines condemns last week’s Atlanta shooting, expresses solidarity with Asian communities]

Soon Chung Park, 74, lived most of her life in New York before moving to Atlanta, her son-in-law said. She was very active, he said, and liked to work. Everyone who knew her said she would live up to 100 years old, he said. Park was close to her family, he said, and she planned to move back home this upcoming summer.

Xiaojie Tan, 49, was known as Emily among friends. People who knew her described her as kind, giving and a hard worker. Tan treated her friends like family, they said.

Delaina Ashley Yaun, 33, was the mother of a 13-year-old son and an eight-month-old daughter, family said. She worked at a Waffle House where she met her husband, her manager said, and she liked to blast gospel music at work.

Yong Ae Yue, 63, loved to share home-cooked Korean food with her loved ones, her son wrote. She was kind-hearted and always willing to help others, he wrote. She loved karaoke.

The six women reminded many people of their mothers, grandmothers and aunties, Liu said: women who sacrifice themselves in search of the American dream, who work tirelessly to make it in this country. Women like Liu’s own mother, who emigrated from China looking for freedom, a better education and a land to call her own, Liu said.

But as Liu processed their anger and frustration, they were overwhelmed by a sense of fear — in the faces of those six women, Liu also saw herself.

“I see myself in the women who were killed, and I see the culprit as someone who used Asian-American women as disposable sexual objects to lust over, dominate and eventually eliminate,” Liu said. “And he didn’t come up with this notion all on his own.”

Andrew Zhang, a junior music performance major, shared his own feelings about living as a person of color in a country steeped in white supremacy.

“Every morning I wake up, and I just wonder if today it’s my turn to die,” he said. “Every single day I have to wonder if my family is still alive … I have to wonder if my closest friends are still alive. I have to wonder if my people are alive.”

In the past year, nearly 3,800 anti-Asian incidents were reported to Stop AAPI Hate, according to research released March 16. 68 percent of the people that reported incidents identified as women.

The rise in anti-Asian hate crimes and incidents has often been connected to the rhetoric of President Donald Trump. Trump has repeatedly referred to the COVID-19 virus as the “China virus” and the “Kung Flu.”

These attacks are connected to a larger, systemic history of racism, xenophobia and immigrant exclusion in the United States, Liu said. They cannot be chalked up to lone wolves or isolated incidents, she said.

“Ever since our ancestors stepped foot on this land, the United States government has deliberately sanctioned and codified anti-Asian racism within its laws, policy and culture in order to sustain and uphold white supremacy,” Liu said.

Liu pointed to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited Chinese immigration for 10 years. At that time, the rhetoric that Asian workers were stealing American jobs flooded across the country, they said.

Then, during World War II, there were the Japanese internment camps, Liu said, and the painting of Asian Americans as agents of foreign espionage. 120,000 people of Japanese descent were held in extreme conditions in these camps.

Liu also cited the “comfort women” during World War II, when thousands of Asian women were forced into sexual servitude in Japanese military-run brothels. That furthered the objectification and fetishization of Asian women, Liu said.

The Asian American and Pacific Islander community has been in the United States far longer than people realize, said Dominic Escobal, a junior biology major and president of the university’s Filipino Cultural Association. But Asian-American history is not taught in textbooks or classrooms. It is a history that folks often must discover on their own and claim for themselves, he said.

“Asian-American history is a history of immigration, colonialism and struggle,” he said. “We have been, and we still are fighting — fighting against racism, fighting against xenophobia, fighting a stereotype … We are not strangers or foreigners to this country. We belong here. And we have no intention of leaving.”

The United States is also a patriarchal nation, Liu added, and Asian-American women experience its oppression based on the intersections of their identity, including race, gender and class.

For Nabila Prasetiawan, fetishization is familiar, intertwined with many of her male friendships. Many times, she said, she has wondered if her male friends were there for her friendship or for her body — for what she represented. She said she has wondered if she could trust them enough to be alone with them.

So, she wasn’t surprised that the white man saw the Asian-owned massage parlors as his sexual temptation.

“Asian-American women are not your temptation. We are not your toys, and we are not your fantasies. Fetishization is racism, hyper-sexualization is dehumanization,” said Prasetiawan, a junior philosophy, politics and economics and women’s studies major and vice president of this university’s Student Government Association. “Do not diminish it as anything other than that, do not gaslight us into thinking that it is not.”

Most of the time, when Asian people speak up about a racist act or rhetoric, their concerns are dismissed and belittled, said Grace Cho, one of the speakers. They’re told, “Don’t worry, it’s not racism,” she said.

And they may find themselves believing those lies, Cho said, because the truth can be too painful to confront. When people of Asian descent are called racial slurs, it’s often brushed off, she said. They’re told that it just means they are smart or pretty, Cho said.

Lei Danielle Escobal, a freshman sociology major, told Wednesday’s crowd that she is afraid of a lot of things — eating spicy food without water nearby, telling someone something personal and then being backstabbed.

But, she said, she never thought she would feel claustrophobic. She never thought she would feel trapped in her own body, scared.

“My body should be a safe space, a home, a sanctuary for all the complexities that I am,” she said. “Instead, my body reminds me that to the world today, the only explanation of myself I get to give is the physical reflection of my ethnic identity. My body reminds me that my voice is trapped, locked within the walls of fear and shame.”

Many see Asian people as property, their culture as commodities, their body as entertainment, Yuxiang Lai said. But the situation isn’t hopeless, he went on.

“I know that this oppressive structure of white supremacy and imperialism will decay and fall apart, but it cannot fall without action,” the junior psychology major said. “But we can’t do it alone. Other marginalized people also faced the same enemies: white supremacy, patriarchy, imperialism and capitalism. These are all forces of reaction. And we cannot vote away our oppressors using their own system.”

Cho, a Korean-American woman and mother of two children, told those gathered on McKeldin that she wants her kids to grow up unafraid and proud to be Asian.

“For too long, we have been told, ‘Don’t worry, you’re fine,’” Cho said. “It is not fine. It is not OK. This is racism. Six Asian-American women were murdered.”

Because of this racism, people will never grow old with their loved ones, Cho said. Children will no longer hug their mothers, and grandchildren will never know their grandmothers, Cho said. Because of racism, there are voids in many hearts that will never be filled, Cho said.

“We are done being told we are fine. We are not fine,” Cho said. “To those who ask us, ‘What are you?’ we say, ‘We are Americans. We are proud Asian Americans.’”

Xinqian “Allison” Qiu, a Chinese-American doctoral student at this university, called for funding, staffing and resources for students, faculty and staff of Asian descent. For instance, the Asian American studies program only has a minor, she told The Diamondback, without a four-year major option.

When she was an international student, she wasn’t confident in her English proficiency or her physical power to fight, if necessary, she said. So she would just “suck it up” when called racial slurs, she said. But she urged other international students from Asian countries to seek help. She encouraged them to educate themselves on race and racism.

“Please remember that, international students from Asia. You have brought your unique character and your natural talents,” Qiu said. “You are a valuable part of our university.”

At the vigil, Pines reiterated that on his first day as president, he had laid out two priorities: to make the university excellent and to create a more multicultural and inclusive community. That same first day, he told the crowd, he had announced that a new dorm would be named after two individuals of Asian descent — part of his message of inclusive excellence.

“Part of being here today is not just to show my support and solidarity for our Asian and Asian-American community, but to tell you that we care about everything that happens to you,” Pines said at the vigil.

When Pines created the term “TerrapinSTRONG,” he said, it wasn’t just meant to be a brand on a mask, he said. It was a representation of the diverse and inclusive campus community, he explained.

“So when you see that mask up on McKeldin Library, it’s a sense of solidarity with every community on this campus, including the Asian and Asian-American community,” Pines said. “Together we are stronger when we are TerrapinSTRONG.”

Elizabeth Hsu, one of the organizers of the vigil, said the community needs not only healing, but change. She called on the university’s administrators to act on their words.

“It shouldn’t have to come down to a couple of students who are grieving and not even having time to process these hate crimes for UMD to say something or do something about it,” Hsu said.

Hsu, a computer science major, urged the university to hire more Asian faculty. Hsu pointed out that there’s a marked difference between the population of Asian students — 19 percent of undergraduates are Asian, according to university reports — and faculty. Only about 11 percent of faculty are Asian, she noted.

She has never had an Asian professor, she said. She said she has only ever been taught by cisgender white male professors in her two years at this university.

“You say that you stand for our community, President Pines,” Hsu said, turning to him. “But you need to actually do something for our community. Issuing emails, statements, and just naming residence halls after trailblazers isn’t enough for us, we actually need change. And we need to do better for the marginalized communities here at UMD.”

The university did not issue a statement regarding the anti-Asian attack until after Choi, Hsu and Larson started planning the vigil, Choi told The Diamondback. She wondered why university administrators did not organize something like the vigil themselves.

“It shouldn’t have been down to the three of us to do it,” Choi said.

After the speeches, the organizers and volunteers lit candles held by those who stood on the grassy lawn, and for nine minutes, the mall was silent: eight minutes for each of the people who were killed in Atlanta and one minute for all the lives lost due to the recent rise in hate crimes.

Dozens of warm, gentle flames lit the McKeldin Mall, as people carefully placed the candles under the portraits of those who died, illuminating the bouquets of flowers and the faces of those who had come to bear witness.

At the vigil, Liu urged folks to sit with their feelings, to sit with their pain. Distancing from the pain is how the movement dies, she said.

“I implore you to use these emotions as the catalyst for movement building and for cross-racial solidarity,” they said. “Our struggles are not limited to the Asian-American community but are felt across all communities of color due to the overarching oppression of white supremacy.”

The University of Maryland’s Counseling Center offers counseling services every weekday from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. You can make an appointment by calling (301) 314-7651.

The AAHC Vigil organizers have compiled a list of anti-racism resources, and you can visit this page for an extensive list of AAPI organizations at this university. You can report an Asian American hate crime incident on Stop AAPI Hate. You can search for a therapist that specializes in treating Asian, Pacific Islander and South Asian Americans in the APISAA Therapist Directory