The melody danced through the floorboards, swirling all across the moody Indianapolis apartment unit. It was a Wednesday afternoon, and Joshua Thompson was hard at work.

A dog paced back and forth, first on the seafoam blue carpet, then on the olive green couch that housed two paint-splattered pillows. His owner was preoccupied, fingers firmly pressed onto piano keys just a few feet away.

The piano was something of an eyesore, a black mark in a sea of color. Thompson’s walls were shrouded with red, yellow and orange paintings given to him by gifted friends. A cardboard dragon rested on a platform on the other side of the room, adorned with pink and blueish pigments.

The piano, sleek and black, seemed noticeably duller. Then, Thompson started playing.

There was beauty, dulcet notes drifting across the room, stringing together one after another like pieces to a jigsaw puzzle. There was madness too, chaos and carnage marked with a muttered curse or a disapproving glare.

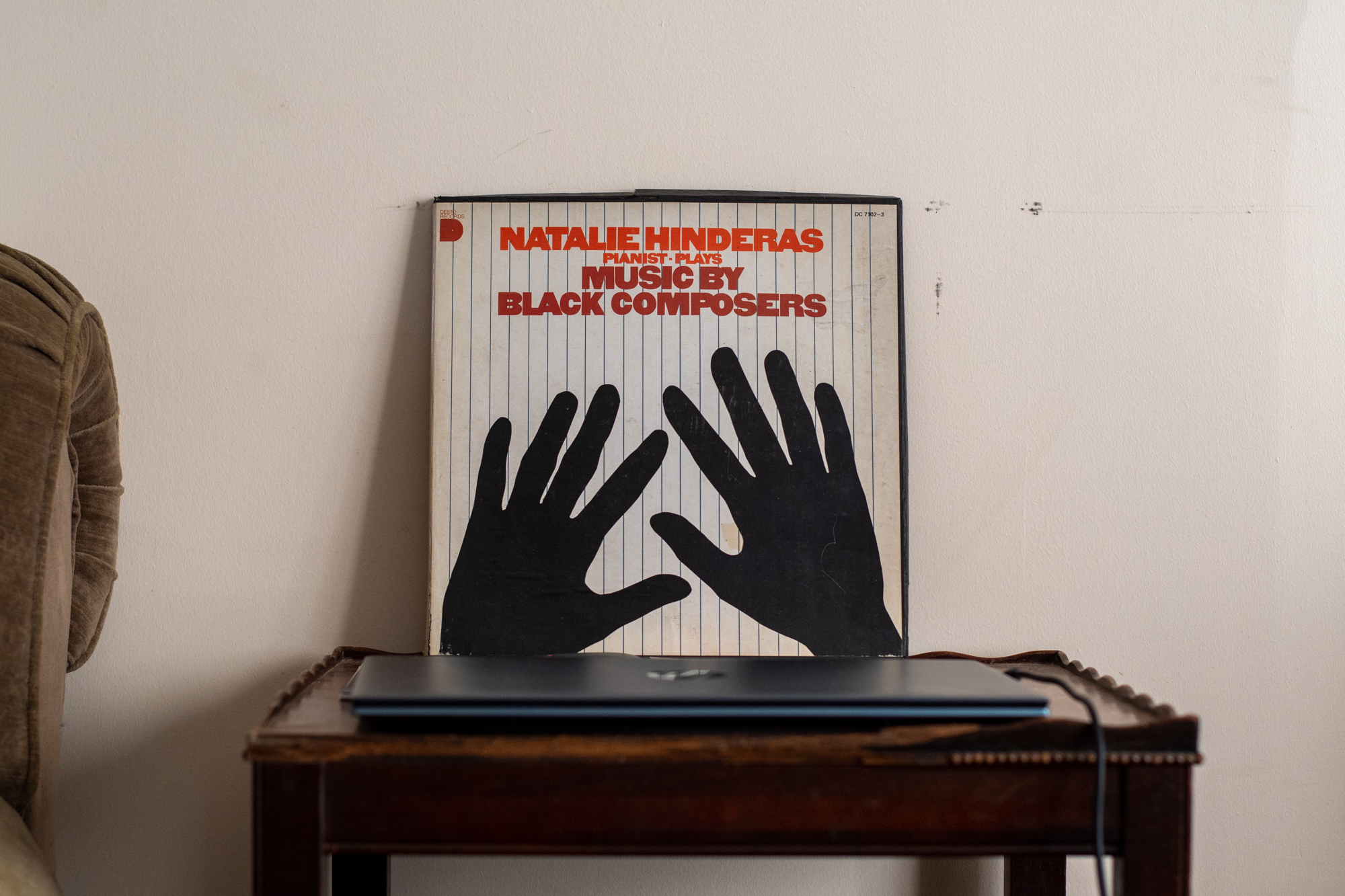

Thompson lay somewhere in between. He’s a classically trained pianist and music sociologist specializing in classical works created by artists of African descent. He’s as much a student of Margaret Bonds and Chevalier St. George as Mozart and Chopin.

He’s also a Hoosier, part of a growing contingent of Black, Indianapolis-based musicians making their mark in the city and beyond. And as the eyes of the college basketball world descend on Indianapolis for the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, those artists will be front and center, performing at different venues across the city.

It’s an opportunity to showcase Indianapolis’ rich musical culture, one that performers aren’t taking for granted.

“Here you get more of a diversity of musical types, but also the world-class musicianship. It’s not one or the other. We get both,” Thompson said.

***

Alan Bacon is well aware of the importance of Indianapolis’ music culture. It’s in his blood. His great-uncle was a musical luminary of sorts in the city, taking the stage alongside big band pioneer Lucky Millinder back in the 1940s.

His dad carried a similar musical inclination. One of Bacon’s earliest memories was watching his father perform at the Pan-American Games as a child. And much like his family before him, Bacon found solace within Indianapolis’ studios and lounges, carving out a 20-year professional career of his own.

“Being around Indianapolis, I kinda fell into the same pathway,” Bacon said.

Bacon’s dedication to the arts has only grown in recent years. Last fall, he and co-founder Malina Simone Jeffers announced the creation of GANGGANG, a cultural development firm dedicated to “producing, promoting and preserving culture in cities.”

The collective helped organize a six-week outdoor music series during the holidays, offering Black, Indianapolis-based artists a chance to rekindle their passion for live performances. It was a precursor of what was to come.

“They provided a COVID-safe venue … and I got to learn about their initiative and what they’re trying to do for art expression in the city,” said Iman Tucker, who performs as DJ IMN. TCKR.

Word got out to city officials, as well. And in advance of the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, Swish was born, a vanguard of art and music designed to both cultivate connections within the city and flaunt Indianapolis’ rich musical tapestry to the world.

A cadre of curators was enlisted, each tasked with helping bring unique sights and sounds to tents and platforms littered across the city. Hundreds of musicians are scheduled to perform over the course of the tournament.

The artistic expression goes beyond music, though. It’s a holistic experience, with visual creators heavily involved. Murals sprawl across many of the city’s walls, often paying homage to Indianapolis’ two loves: beats and basketball.

Indianapolis’ adoration of hoops has been discussed at length. But, it’s that second passion, music, that has burbled underneath the surface. Now, it’s ready to break out.

***

The sweet sting of incense hit the air as soon as Thompson pulled his lighter away. He sat on one side of the room, a fair distance from the grand piano he had hunched over just hours earlier.

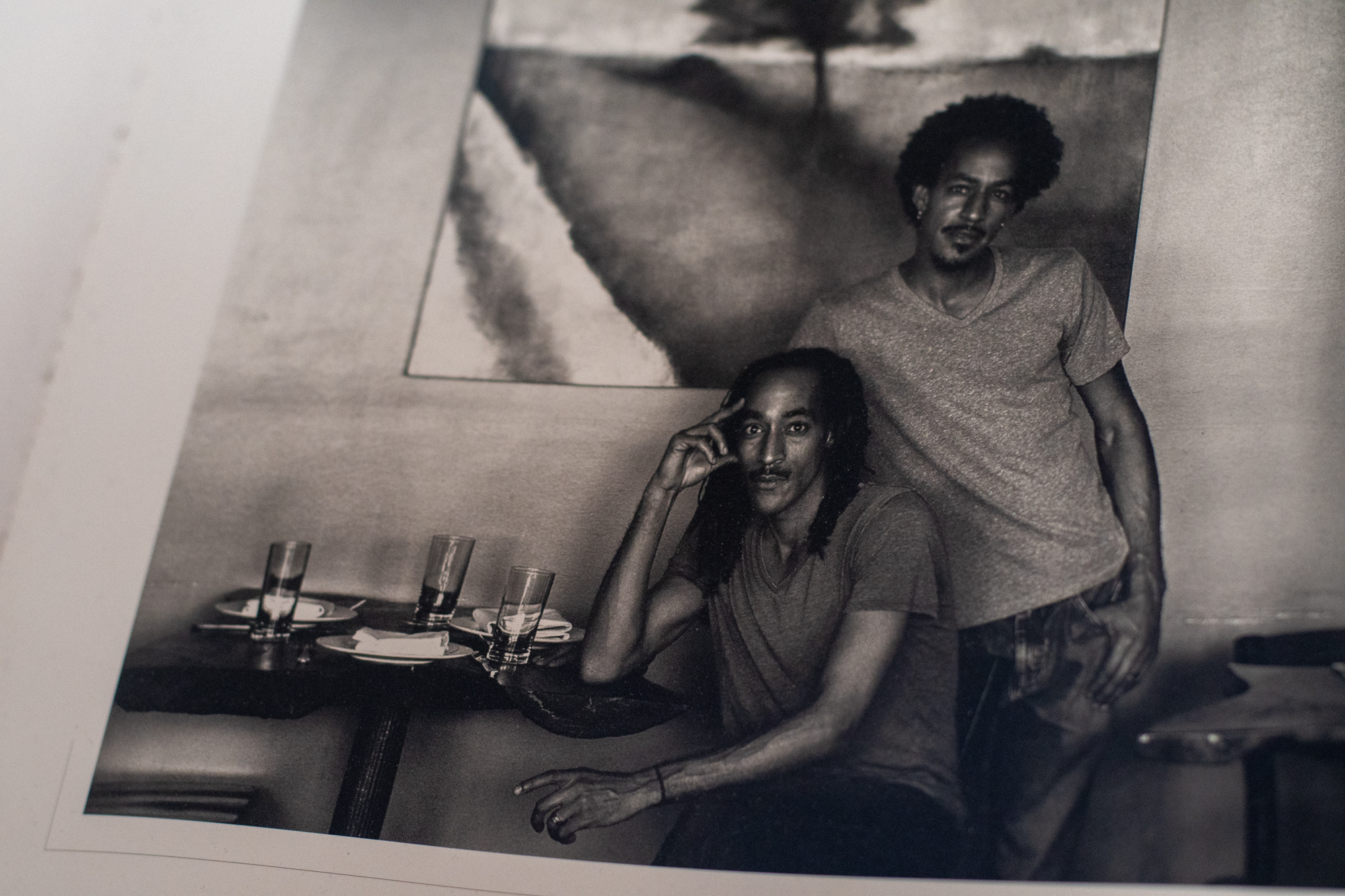

There was a new source that caught his focus: friend and frequent collaborator Richard “Sleepy” Floyd. Floyd is one of Swish’s curators, using his extensive connections across the city to find talent for the tournament proceedings.

He’s also a skilled musician in his own right. Floyd is a drummer and producer, part of the jazz-influenced band Native Sun.

And as Floyd sat in the corner of Thompson’s living room, chatting away under the haze of incense fumes, the pair’s connection was clear. They come from vastly different musical backgrounds — Thompson prefers the classics; Floyd opts for jazz and hip hop. Still, they are bound together through their love for the city’s Black music.

It’s more of a quilt than a blanket, with different musical stylings weaving together over the years. Whether it’s rap, classical, blues or folk, all sorts of music are cherished within the community.

“It’s always a melting pot of different genres that come together,” Floyd said. “That’s what’s cool. It’s different races, different backgrounds. We’re just all on the same page with one common goal: just to be the culture.”

Much of “Nap Town’s” culture stems from its past. Famed figures like guitarist Wes Montgomery, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and trombonist JJ Johnson helped pave the way, drawing eyes and ears into the city throughout the early- and mid-1900s.

Indiana Avenue was their canvas. It was Black Indianapolis’ cultural hub, a place where Black Hoosiers could find relief and comfort outside the reach of white supremacy. The streets were lined with jazz clubs and theaters.

“The African-American culture has been … rich,” saxophonist Rob Dixon said. “I think that it’s been reflected in a lot of the things that happen on the scene today.”

Indianapolis’ rich musical heritage has stood the test of time, fueled by a commitment to storytelling and painting an accurate reflection of life across different intersections of society.

And although the mediums have changed, it’s that pursuit of true artistry that has come to define the Indy sound.

“I think it’s more of a mindset than an actual sound that you can pin yourself to,” Floyd said. “That mindset is something that drives the sound here.”

***

Dixon was one with the rhythm. He drifted back and forth atop the makeshift stage, caught up in a daze as melodies spilled out the end of his tenor saxophone. A small crowd congregated, swaying and nodding as Dixon, Floyd, bassist Willie Robinson and keyboardist Shawn McGowan churned out tunes on Georgia Street — one of Swish’s three venues — on March 13.

Dixon, an Atlanta native, has seen it all during his lengthy career. He’s a regular at Indy Jazz Fest, an annual festival highlighting Indianapolis’ contributions to jazz. He’s recorded multiple full-length albums, carrying on the traditions of Indianapolis’ past jazz titans. And in 2015, Dixon was inducted into the Indianapolis Jazz Hall of Fame.

But for Dixon, commonly called the “Musical Mayor of Indianapolis,” the festivities surrounding the NCAA men’s basketball tournament offer something different: a coronation for Indy’s thriving art community. It’s an aspect of Indianapolis’ culture that has been obscured at times.

“Indianapolis is … not only known for amateur sports or just sports or race car driving but [also] music and art and culture and dance,” Dixon said. “The well runs deep.”

Dixon’s belief is shared among those involved in “Swish’s” production. Indianapolis’ music community has suffered at times amid the strain of COVID-19. Live performances have evaporated, taking away a key part of artists’ incomes.

Still, the city’s Black musicians have continued to make their voices heard. Indy Jazz Fest was held virtually last November. Now, there’s Swish, a window into the lyrics and instrumentals that have soundtracked the lives and experiences of Black Hoosiers across the city and state.

“It’s amazing because this is what we do, this is who we are and if we don’t do it, then we feel a big void in our life,” said Valerie Phelps, who’s part of jazz and gospel quarter, The Phelps Connection. “Without music, we don’t survive.”

This dedication to artistry pushes Indy’s Black music scene forward. It’s a dedication shaped by the city’s history, fostered during the Great Migration when names like Montgomery, Hubbard and Johnson lit up marquees on Indiana Avenue.

And it’s a dedication that will be evident once again when Indianapolis’ Black artists perform throughout the tournament.

“This is the beat and the vibe and the melody of this city, whether there’s conferences, tournaments here or not,” Thompson said. “This is just what we do. And this is what we sound like.”