Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

Over spring break, I went to a Chinese market for the first time in months. On the street outside, I noticed that flags were at half-mast, a reminder of the recent shootings in Atlanta that left eight people dead, including six Asian American women. In light of this, I thought the store would be emptier than normal.

However, inside it was just as busy as ever. People milled around between narrow produce aisles and over the sticky floor near the butcher’s counter. Over shoppers’ heads, the distorted voice of a Cantonese singer crackled through a broken speaker system. Even though the world went on as normal, his unintelligible words conveyed the stress and frustration many feel about the increase in hate directed at Asian Americans over the past year.

I’m not really surprised that this shooting happened. If anything, it was really only a matter of time, given this country’s pattern of mass shootings and racist language. It doesn’t take a genius to assume they’d combine sooner or later.

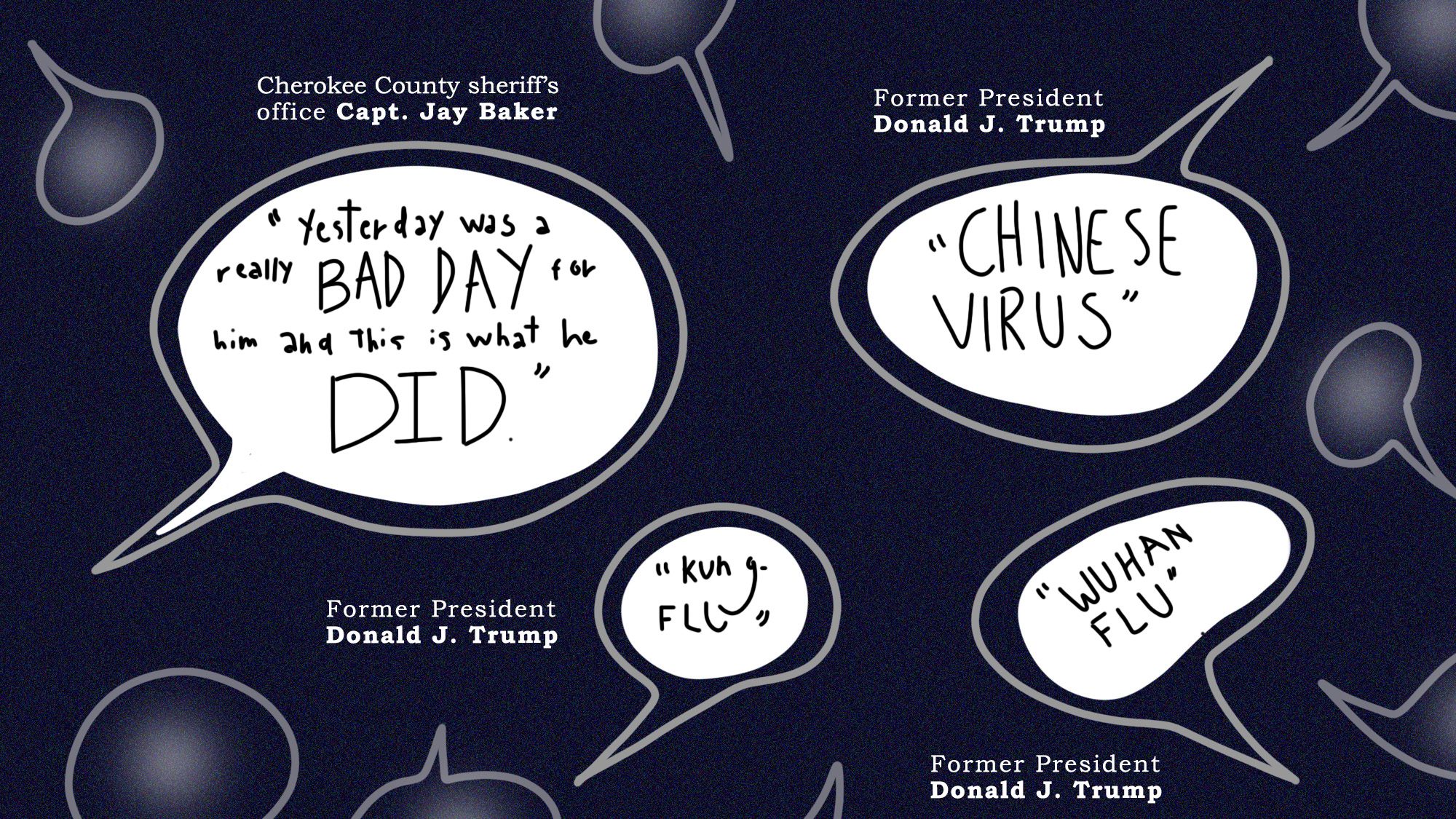

What I am shocked by is how public servants continue to use irresponsible, callous language even after this horrible event.

According to Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office Capt. Jay Baker, the shooter was “fed up” and having a “really bad day,” making excuses for the shooter in the way a negligent mother excuses a naughty child.

The sheriff who tried to clean up this PR mess stated Baker had “personal ties to the Asian community,” as if that excuses his statement. Well thank you, Captain Obvious. Everyone knows an Asian person in America — it’s almost as if there are Asians living all over the country. And what’s with the term “Asian community”? We don’t belong to a cult that meets every week for tea and rice cakes. This term only adds to the perpetual foreigner stereotype that says Asian Americans aren’t part of normal American society, instead consisting of an entirely separate community.

I’m not being petty with word choice because I want to verbally bully some public figures. I’m pulling apart these statements and drawing out what they imply, because implicit messages do a lot more damage than they may seem to do on the surface.

Those words, such as the shooter’s assertion that his actions were due to a sex addiction and not racially motivated, deny the reality that gender and race are inextricably linked in many people’s lived experiences and the public consciousness. His targeting of Asian American-owned businesses shows that he associated Asian women with sexual temptation, probably coming from the stereotype of Asian prostitutes and massages, or at the very least, the perpetually detrimental Yellow Fever, blending sexism and racism into a disgustingly time-resistant smoothie.

Without “sex” implying “Asian women” to him, the shooter probably wouldn’t have targeted businesses he knew employed Asian women.

This is why we all need to be careful of the language we use. Whether or not it’s meant in a joking way or clearly a stereotype, massages in Asian establishments obviously don’t all end in sexual favors. Word choice can betray perceived realities in both the speaker and listener’s minds. Language shapes our perceptions of each other, morality and acceptable behavior — all things that in turn, have serious impacts on people’s lives. As we saw this week, that’s especially true for minorities and people who have less power in American society, such as women, sex workers and those who don’t speak English.

But while everyone is responsible for their speech, public servants in particular must be more conscious of their words, especially in light of the current context regarding Asian people and anti-Asian racism.

For police, this could be as simple as letting their public relations professionals read over public statements before they’re given. Beyond that, they can think about how individual biases might be affecting assessments of crimes. Baker and his coworkers probably already knew there were some issues with how he perceived Asian Americans, if his “CHY-NA” T-shirt controversy is any indication. Given this, maybe he shouldn’t have been tasked with heading this case or speaking to the public about it in the first place.

For politicians, don’t be racist in public — again, this is a place where PR people or other pairs of eyes should check over statements. Steer clear of language that blames Asians for the pandemic. And maybe, even though it’s kind of redundant in policy circles, make more of an effort to separate growing tensions with the Chinese government, for example, from Chinese people. Even though the Chinese Communist Party, Chinese people, Chinese Americans and Asian Americans are pretty different groups, many people tend to not care about the difference. Linking Chinese people with whatever shady CCP policies the U.S. opposes ends up villainizing these people and, by extension, the Asian Americans who look like them.

Being careful about implicit racism in words is, of course, not a substitute for not taking racist actions. If the shooter had stayed silent about his motivations, he’d still be misogynistic, racist and responsible for eight deaths. But there are many other people — whose word choices purposefully or implicitly link sex, Asian women, solving problems with guns and expendable lives worth less than some “temptations” — who are at least somewhat culpable for convincing the shooter his plans were acceptable.

Jessica Ye is a freshman government and politics and mechanical engineering major. She can be reached at jye1@terpmail.umd.edu.