I FaceTime my grandmother — vovó, in Portuguese — about once a week. She lives in Goiânia, Goiás, a town in Brazil that has reached 100,000 COVID-19 cases.

I try to cheer her up, telling her the silliest things that make her say “Ah nem, Clara!” — the equivalent of “Clara, stop.” Sometimes, she’ll tell me to not date American boys. Don’t do anything that will make you stay in the United States.

“Just come back home,” she tells me in Portuguese.

Mostly, I tell her I miss her. I tell her I miss swinging in the hammock as she waters her roses. I tell her I miss taking her to the movies. And then, I tell her I miss her biscoitos de queijo.

“Ah nem, Clara,” she goes with a laugh “I don’t even make those anymore.”

I ask her for the recipe. She says she doesn’t remember.

Now, I beg to differ. I think she does remember. She just doesn’t tell us. She never did tell us her recipe. Whenever we watched her making the biscoitos, we would find out new things — different measurements of butter or a tad of milk cream that was never mentioned before.

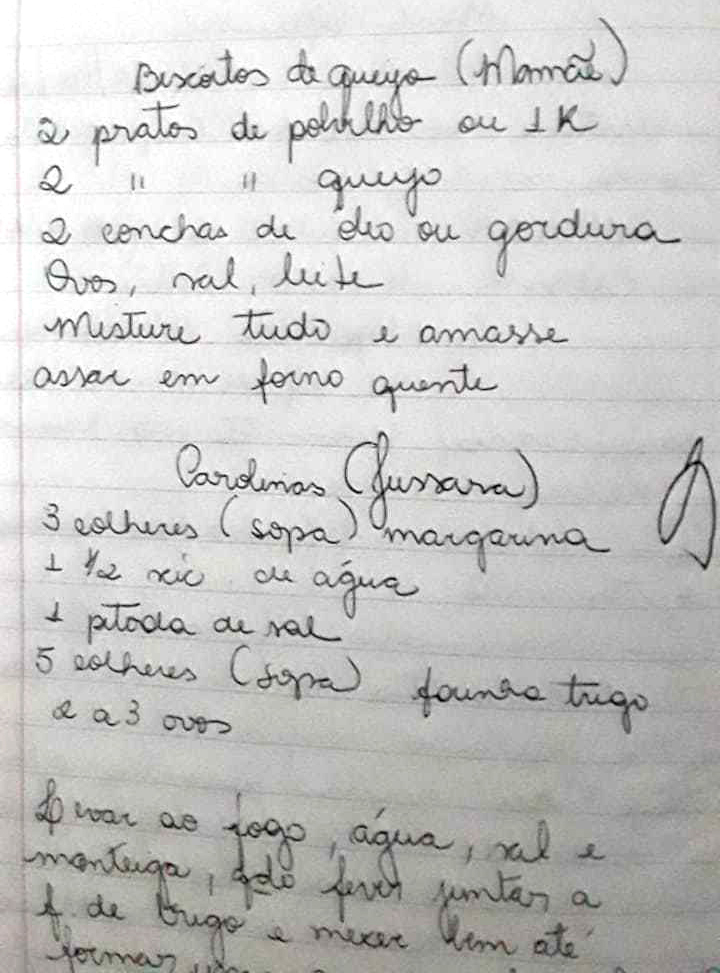

One thing I was able to get from her, in one of these FaceTime calls, was this:

“You just go by the eye, you have to feel the dough.”

What is biscoito de queijo?

If you ask any Brazilian, they will tell you it’s the same thing as pão de queijo, a cheese bread that gringos — non-Brazilians — are more familiar with. But if you ask a goiano, someone from the state of Goiás, they will tell you it’s an entirely different thing.

A biscoito de queijo is crunchy on the outside, soft on the inside. It tastes like sunny days, butter and aged cheese. During summer vacation at my grandmother’s house, I would eat it for breakfast, mid-morning snack, with afternoon cafézinho and sometimes as a late-night snack.

The true origin of biscoito de queijo isn’t certain. Some say that the pão de queijo — which is similar to the biscoito — recipe dates back to the 18th century, during the slavery period, when high-quality flour was not widely available. Instead, Brazilians would use yuca for most of its recipes. Yuca was — and still is to this day — a common food among native people in Brazil.

Every goiana family has its own recipe, most likely crowned by the grandmother. As a kid, I would spend hours next to my grandmother, peeking at her mixing the polvilho (like manioc starch), the eggs, the cheese. I waited patiently until it was time to roll it into shapes. It was my favorite part (but as my mom says, only because it was the only thing I did).

[Quarantine Obsession: Bring the beach to your dinner table with these simple fish tacos]

We would start by rolling the dough into cylinders, pressing a fork against them and shaping them into the letter “c.” Sometimes, I would make it look like a cartoon bread, keeping it a simple cylinder and with diagonal lines.

One thing you must know about Brazilian recipes, especially those that originate from rural families in Goiás: the recipe-owners lie.

When they say “one cup,” it does not mean “one cup.” If it’s “one cup” of polvilho, it means an incredibly generous cup of polvilho. The polvilho must form a mountain top.

But if you are talking about one cup of oil, it needs to be one finger below the “one cup” measurement.

If it’s butter, be generous.

What I mean to say is, my mom and I had to try this recipe a couple of times before getting it right. But I think it’s part of the process. I think biscoitos de queijo are something magical, that each one of us must have a unique recipe. Maybe it’s a metaphor for something. Maybe it’s just a welcoming distraction from quarantine.

The original recipe, the one we got from my aunt that she says she got from my grandmother, is this:

2 cups or 1kg of polvilho doce (like manioc starch, but not quite)

1/3 cup of oil

1 soup spoon of butter

2 large eggs

2 cups or 1kg of cheese (traditionally, the minas type)

A bit of salt

1 cup of milk

The results? It was good, but a bit soft for our personal taste. So, we tried again.

Our recipe comes from three different people: allegedly my grandmother through my aunt (who also sent her own recipe), and my maternal grandmother.

My mother remembered that when her mother wanted the biscoito de queijo to be crunchy, she would use butterfat in the dough. So, she decided to use heavy whipping cream rather than milk and butter.

Additionally, we did not have the traditional minas cheese. We used Lupita’s cotija molida, a grated Mexican-style cheese.

[Fan fiction is proving to be more than just a hobby]

After three trials, here is our new family recipe:

1 cup of oil (but with one finger less)

2 large eggs

2 cups of cheese (be generous. Make a little mountain top.)

2 cups of polvilho doce (be generous. Make a little mountain top.)

1 cup of heavy whipping cream (normal cup measurements apply to this one)

Salt

One note about the polvilho doce, or sweet manioc starch. It must be sweet, and it must be grainy. It should not look like powder. You can find it at any Brazilian market store (or on Amazon).

Preheat the oven at a very high temperature. 480 degrees Fahrenheit is a good one. Make sure to preheat at least 30 minutes before baking.

Mix the cheese with the polvilho and the salt in a bowl, the largest you have. Add the salt little by little. You’ll have to try the dough later, after you mix all the ingredients. It must be salty, like drinking sea water. If it’s not salty enough, you can adjust it.

Then, make a little hole in the center and add the oil to it. Mix it. Then, add the eggs.

You will need to knead the dough, like you would with bread. The best way is to use your wrist. Imagine your wrist is a rolling pin, and copy those motions. Knead the dough until it has a velvety, thin texture.

As I kneaded the dough, my mom rolled it into shapes. For this part, we decided to roll it like her mother used to. She would knead the dough a little bit herself, too. Then, she would shape it into a cylinder, mark it with the fork and tie it in a knot.

In total, we made almost 50 biscoitos de queijo. We put them in three different pans (no need to grease it) and left them in the oven for about 12 minutes.

Throughout the whole process, I kept in mind what my grandmother said and what my mom echoed — to feel the dough. I couldn’t feel much, to be honest. The dough felt a bit too sticky in my hands. I felt anxious because I wasn’t sure I was doing it right. I was too eager, too perfectionist and, at that point, too impatient and hungry.

Last year marked the first time in a while that I didn’t return home for the summer, that I didn’t swing in my grandma’s hammock in the garden filled with roses. Each time I talk to my grandmother, she tells me she is tired of quarantine. She wants to see her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Each time, she asks me — will I see you in June?

There is something inherently Brazilian, inherently goiano, inherently my grandmother, in these biscoitos de queijo. Something hard to explain to an outsider.

What I can say is this: when I tried the biscoito de queijo, I felt something else. I felt back home.

(Sorry for being cheesy … but it’s a biscoito de queijo recipe, so what were you expecting?)

CORRECTION: Due to a reporting error, a previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Brazilian town of Goiânia has reached almost 400,000 COVID-19 cases. Though the state of Goiás has almost 400,000 COVID-19 cases, the town of Goiânia has reached 100,000 COVID-19 cases. This story has been updated.