The press events ahead of the 2005 Super Bowl were as rowdy as usual. Journalists made the rounds, catching up with old friends and exchanging remarks about the game. Amid the hustle and bustle, one individual stood out. It was Philadelphia Daily News and Inquirer columnist John Smallwood, walking around the press box and introducing people to his infant daughter, Ryan.

“From that moment on, we never had a conversation or exchange that didn’t include him talking about her,” journalist David Steele recalled.

The interaction was the epitome of Smallwood’s character: equal parts prolific journalist and loving father. Smallwood, an alumnus of the University of Maryland, seldom had a chat in a press box without mentioning his family.

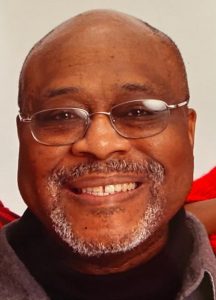

Acclaimed for his headstrong opinions and honest prose, Smallwood is regarded as a trailblazer in Black journalism, finding success in a predominantly white niche, and remembered as a family man, always proud to show off his daughter. He died Dec. 6 after a long illness at the age of 55.

“He was also a heck of a journalist, but I think he would want everybody to know that he was a terrific dad first,” his friend Milton Kent said.

Smallwood spent more than 20 years years as a reporter and later columnist at the Philadelphia Daily News and Inquirer, capturing the essence of the city’s sporting culture with his prose — and paving the way for other Black writers in the process. From his journalistic education at this university to his later years, Smallwood was regarded as a writer dedicated to his craft and humble in his work.

There was also the other side of Smallwood. The one that spoke glowingly about his family, that lit up rooms with his smile and confidence — the one that plastered his Facebook timeline with photos and videos of his daughter’s dance recitals. And it was that balance that made Smallwood remarkable, his friends said.

“You can get into a lot of different spaces with people from different, different perspectives. And Johnny stayed consistent, there,” his sister, Pam Candelaria, said. “He was very much a family man all around.”

Ike Richman remembers Smallwood for his drive.

Richman first met Smallwood at a journalism class at this university. But back then, Richman only knew him as he introduced himself: “John from Baltimore.”

It was there the two developed a bond as budding journalists and close friends. Though they took up different journalistic routes — Smallwood wrote for The Black Explosion and The Diamondback, while Richman got involved with WMUC — Richman recalls Smallwood’s passion.

There were the long nights when Richman would walk across the hall to find Smallwood working on his craft. And there were the days in class when Smallwood was constantly talking about his dreams. For Richman, one thing was clear: Success was in Smallwood’s future.

“You could see then, he was determined,” Richman said. “He knew what his dream was, and nothing was going to stop him. He was going to be a sports writer, you knew it.”

Steele noticed the same about Smallwood. Though Steele was two years older when they first met, he was immediately struck by Smallwood’s drive from the earliest days of their friendship.

“You knew that he was gonna be one of the guys who was gonna go a long way … when school was over,” Steele said.

Smallwood wasn’t the first Terp in his family. Candelaria also attended this university, studying journalism, and graduated three years before her younger brother.

Smallwood was still in college when he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It was a challenging time for the whole family. But it was an obstacle Smallwood was always determined to overcome, Candelaria said.

“He always took it as, ‘This is something that I’ve just got to deal with and move on. It can’t define me,’” Candelaria said.

And move on he did. His cancer went into remission, and after graduating from this university, Smallwood took what Candelaria described as the “quick track” to professional journalism. He accepted a job in Rochester, New York, covering mostly high school sports and smaller colleges. In that environment, he thrived as a reporter, emerging as a talent in the industry.

And in the media landscape, Smallwood made waves. Not only was he a skilled writer in the field, he was also one of the few prominent Black sports journalists.

“We were young, Black and in sports journalism. There had not been a place for us before,” said Garry Howard, a friend and former colleague. “So in a lot of ways, this group of writers was breaking ground.”

When Smallwood landed a job at the Daily News in 1994, the racist outcry was significant. A Black reporter working in a major media market, Smallwood broke down barriers — and faced criticism and discrimination from both inside and outside the business. Some claimed Smallwood was merely a “quota hire” and hadn’t earned the job, said Steele.

“There’s resistance from the outside, and there’s a lot of resistance from the inside, from people within the business who really resent seeing us reach that level, as if they’re having something taken from them,” Steele said.

Smallwood continued to excel, blocking out the noise while remaining steadfast in his reporting and insightful in his columns.

“The conclusion that we always came to was: There’s going to be people who are never going to be happy, never satisfied, never supportive of anything that you do. So why ever try to satisfy people like that?” Steele said. “Just go and do what you do and write what you want to write.”

As Smallwood rose through the journalistic ranks, national accolades and recognition stacked up. He developed a reputation for honest, clean reporting, and was known for showing genuine empathy in his columns, his colleagues recall.

There were times, though, when Smallwood recognized the coach had to be called out, the quarterback had to be criticized. But in those moments, he was unfailingly fair.

“He wanted to be able to sit across the table from this coach or this general manager or this quarterback and say to them, ‘OK, I wrote these things that you perceived to be negative, but you need to tell me how they’re not right, how they’re not fair. If you can’t tell me that, then I don’t think you have a complaint,’” Inquirer columnist Marcus Hayes said.

Smallwood was also determined to never abuse his influence as a columnist, Hayes said. Though one of the more accomplished journalists in any room he was in, Smallwood was always willing to engage with other writers.

Kent recalls long conversations at a TGI Fridays in Greenbelt after Maryland games. It was a popular place for alumni to gather and talk sports, and Smallwood listened intently — no matter who was talking.

Colleagues also lauded Smallwood’s understanding of the field and the difficult dynamics that often came between reporters and columnists. In a sports-obsessed city like Philadelphia, Smallwood would hunt down smaller stories.

This meant championing sports that drew considerably less attention. He wrote about men’s lacrosse, women’s basketball and even dabbled with auto racing. Meanwhile, he left opportunities for his fellow reporters to write about Allen Iverson or yet another disappointing season for the Eagles — because he had been in their shoes before, Hayes said.

“John was pretty deferential when it came to that. He understood that if he took the shank of the story, especially when the teams were bad — and most Philadelphia teams are bad — then it would leave the beat writer very little food,” Hayes said.

More than anything, though, Smallwood was a family man. Friends remember the massive smile when Ryan came up in conversation and the big laughs that radiated around whatever room he was in, especially when he was talking about her. They respected that he lived in Delaware to be close to his mother and that he found balance between writing and spending time with those close to him.

And, for his sister, Smallwood is remembered as the man who would drop anything just to go to his daughter’s dance recital.

“He adored his family. He would do anything for his family,” Candelaria said. “And he made sure people knew it.”