Gentle piano music played as photographs of Lakeland memories faded in and out of the screen.

Reverend Joanne Braxton held her palm to her heart and dabbed her eyes with a tissue. Certain photos brought about chuckles and smiles among panelists.

In partnership with the University of Maryland’s American studies department and the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, on Thursday, the Lakeland Community Heritage Project shared selections from the more than 6,000 photographs, personal documents, letters and official records it has collected over the years from those who either once lived or currently live in the historically Black neighborhood in College Park.

More than 150 people attended the virtual event, called “The Lakeland Spirit: Through Digital Footprints.”

Panelists at the event included various researchers and scholars, many of whom shared connections to the neighborhood, which was devastated by gentrification in the early 1970s.

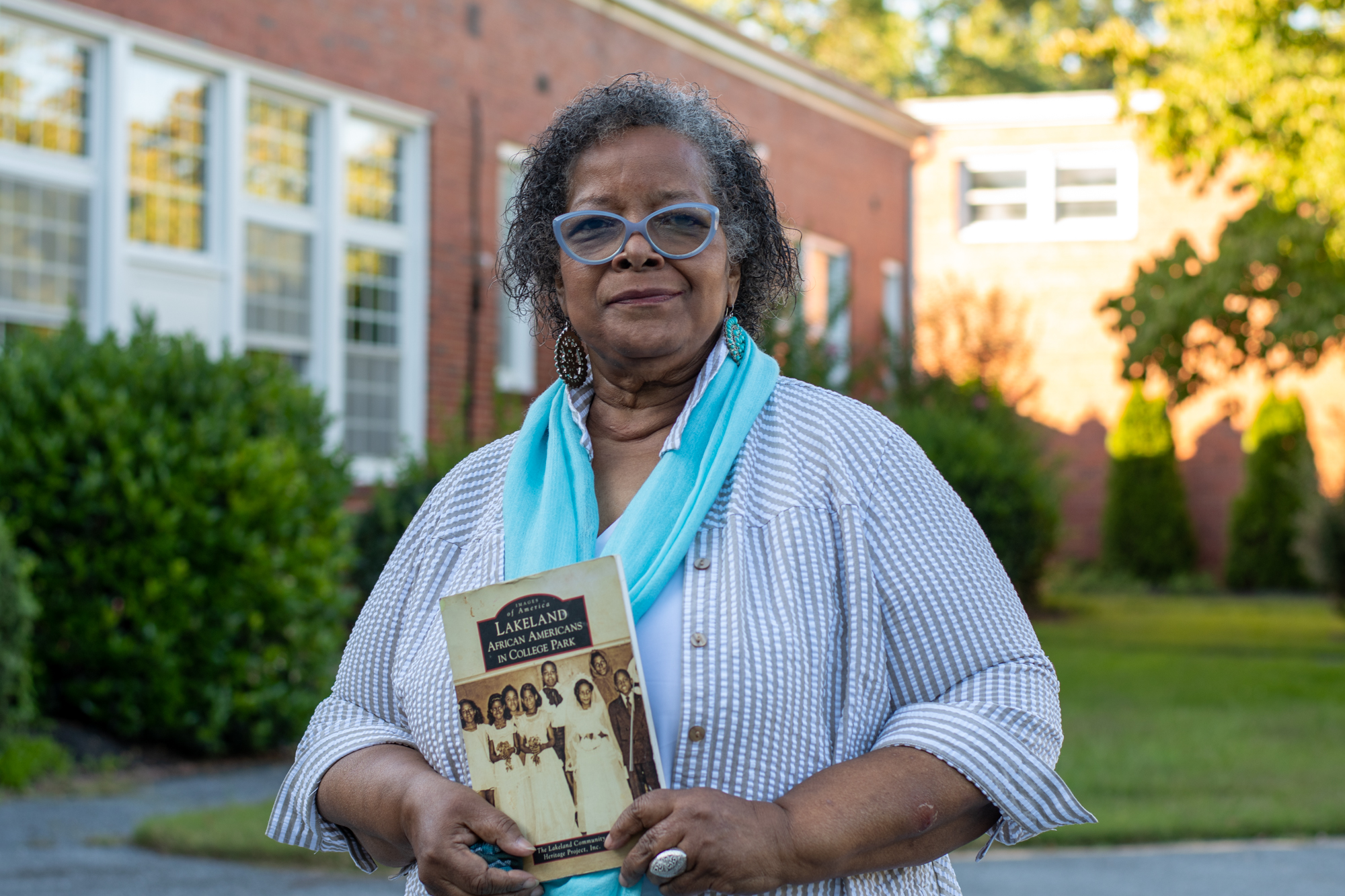

One of the panelists, Violetta Sharps Jones, is a fifth-generation Lakelander and has been doing genealogy research since 1990. After starting out by plotting her own family’s roots, she slowly branched out to document the genealogical history of Lakeland.

She often wonders what it would be like to have a family tree that would show all of the relationships and connections in Lakeland since its first families arrived in the 1890s.

“Lakeland was built on those families, and it was the families that sustained Lakeland,” Sharps Jones said.

Avis Matthews, another panelist, is descended from Lakeland residents — her mother’s family was born and raised in the community. Matthews, an alumna of this university, researches how African American communities in Prince George’s County upheld their racial and cultural identities during the time of desegregation.

Matthews explained that Lakelanders advocated for educational justice in the community and that the community was extremely connected to the schools in the neighborhood. When desegregation came around, many residents feared their schools would be closed down, as Black children were moved to schools attended by white children, and actively worked to defend them.

In one document Matthews shared, a concerned parent worried that moving Black children to schools attended by white children was fiscally impractical, considering the Lakeland school was under capacity and the school attended by white children was overcrowded and would have to build temporary housing for the incoming students.

Matthews also shared a memo Lakeland resident Billy Weems wrote to the community about the testimony he gave at a school board meeting, where he fought against the closing of the Lakeland school. In the memo he says, “the way things are now, the giant eraser is ready to wipe us out. And it will be like we never were.”

“It really gives you the sense of how Lakeland is with feeling as if their school and their community was sort of slipping away from them,” Matthews said.

Ultimately, though, the city closed Lakeland Elementary School in the 1970s, tearing down two-thirds of the entire neighborhood by the mid-1980s. The Lakeland High School building still stands today on 54th Avenue, but it is now home to the Washington Brazilian Seventh-day Adventist congregation.

[For those raised in College Park’s Lakeland, the wounds left by its destruction remain]

Braxton is the great-granddaughter of one of Lakeland’s founders. She was also the David B. Larsen fellow in spirituality and health at the Library of Congress John W. Kluge Center. There, she examined thousands of original documents for her project “Tree of Life: Spirituality, and Well-Being in the African American Experience.”

Braxton showed a picture of her brother’s coffin being carried at his funeral in 1980. The church where it was held was so full that people were standing, she said. She connected this image with the same Weems memo about erasure. Braxton and her family said that her brother died from a broken heart after giving his last full measure of his love to try and save the Lakeland school and defend his community. The wreath on his coffin was in the shape of a broken heart.

“No one who was present at that funeral that day failed to understand the connection between urban renewal and Billy’s broken heart,” Braxton said.

The final panelist was Marya McQuirter, curator of the dc1968 project, a digital storytelling project about the year 1968 in Washington, D.C. She doesn’t have any personal ties to Lakeland, but she was one of the early 1970s elementary school students in Prince George’s County who were bused from a majority-Black school to a majority-white school as part of a desegregation mandate.

McQuirter has expertise with archives and archival objects. She was excited about the archival materials from Lakeland because, she said, because it showed what people found important; she said she liked to imagine someone putting them in their photo album. But they also allow people to think more critically about the photos in the context of segregation, desegregation and urban renewal.

“They give us a sense of daily life,” McQuirter said.

[Systemic racism has plagued this College Park neighborhood. Now, the council apologizes.]

Omar Eaton-Martìnez, assistant division chief of historical resources for the county’s parks and recreation department, was the event’s facilitator. One of the first things he asked was for the panelists to talk on the trauma of erasure.

Braxton recited a poem she wrote as a college sophomore about 50 years ago, an example of the way she has coped with the trauma that still exists.

Matthews explained that desegregation was traumatizing for Black communities, since it often came with the closing of Black schools. Schools were symbolic in African American citizenship, she said, because they represented staking a claim in the place they had settled.

Sharps Jones shared the story of a day when her and her three sisters decided to take a walk around Lake Artemesia. It was emotional for them, she said, because it had been a long time since they were in that area and they could recognize virtually nothing. Sharps Jones and her sisters sat on a bench and watched people biking and jogging, wondering if they were aware of the rich history the area held.

A man sat next to her, she said, and she was compelled to ask him if he knew about the thriving Black community that existed since the 1890s and about the urban renewal that removed it. He was shocked and said no. There was nothing there to even suggest it, he said.

“We need to have more tangible evidence that these people came and they stayed, and they created this wonderful community,” Sharps Jones said. “We cannot let them be forgotten.”